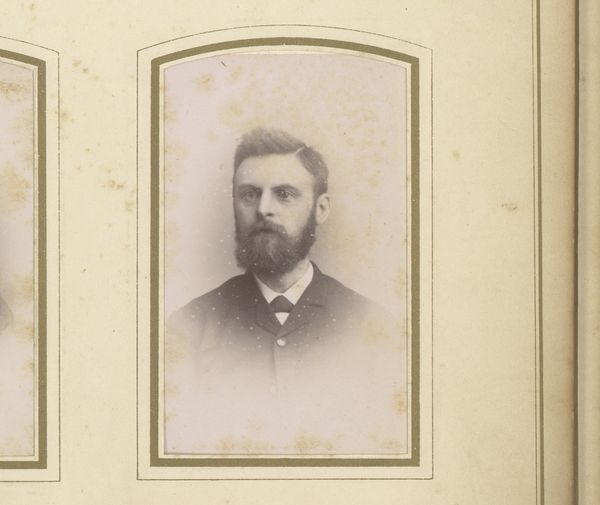

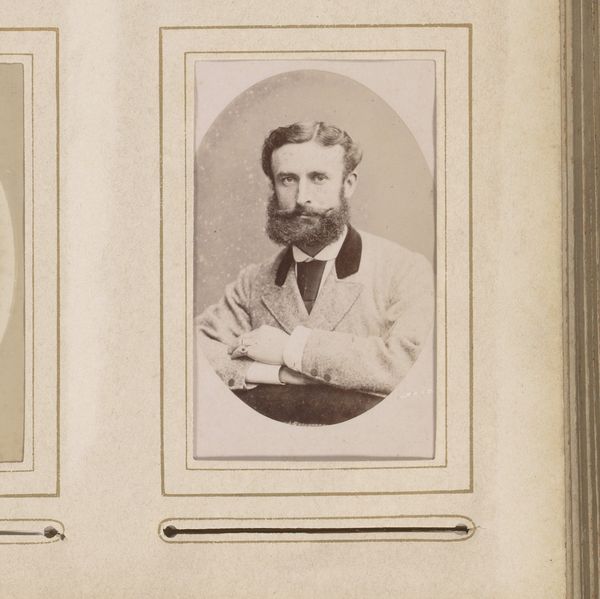

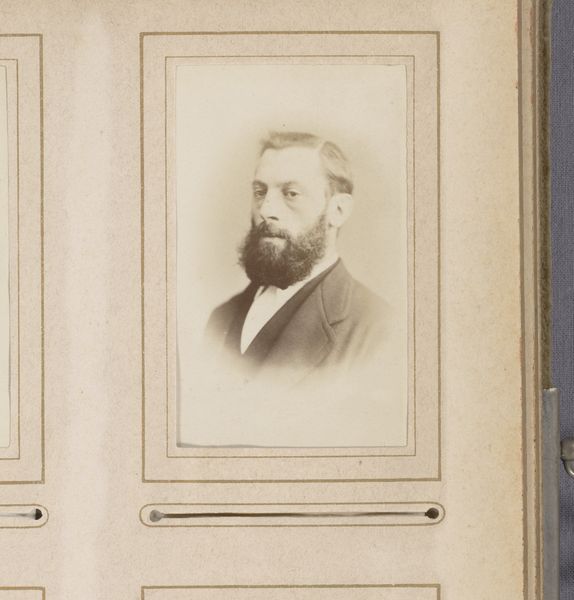

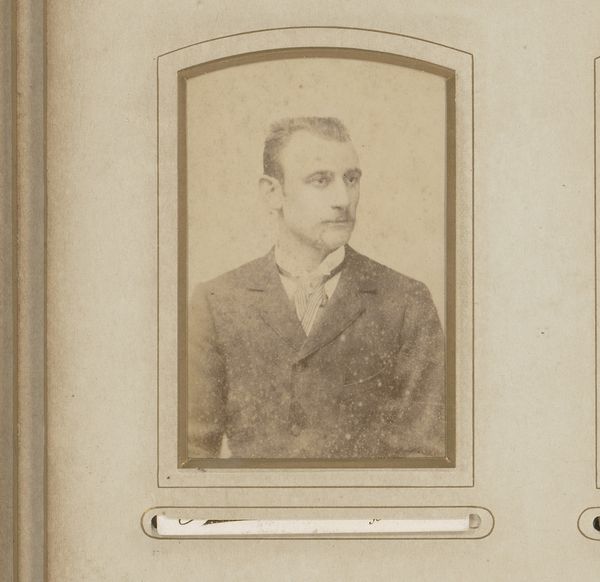

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

charcoal drawing

#

photography

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Today we are looking at "Portrait of a Man with Beard" dating from between 1875 and 1877, found here at the Rijksmuseum. The artist identified as Bernardus Bruining captured this likeness using an albumen print technique. What are your first impressions? Editor: My immediate thought is reserve. There is such carefully arranged composition and solemn formality, even somberness, despite its relatively small size. Curator: That reserve seems characteristic of portrait photography during this era. Albumen prints, developed from glass negatives, allowed for incredible detail. Consider how meticulously Bruining captures the texture of his beard and the fall of light on his face. Editor: Yes, and how fascinating that photography, a technology perceived as democratizing art, becomes, in this instantiation, so much aligned with ideals of bourgeois formality and identity. Look at his confident pose, even defiant. Curator: Indeed. The rise of photography allowed a broader segment of society to participate in portraiture, to assert their place in the visual record. The portrait provided social currency. Editor: Photography was perceived as offering a more truthful representation than painting, of course. What is concealed beneath this serious expression, this modern businessman, captured in this time? Curator: Perhaps, but truth is mediated through composition, lighting, pose. Photography does not provide unvarnished reality; rather it reframes our view. Think of this in terms of Realism which arose as an art movement around this period, and this image is of the same school of art. Editor: True. The subject clearly intended to project himself as dignified and successful, embedding himself in the cultural narrative. What do you think that an audience might have looked for when looking at this kind of image in that day and age? Curator: In contemplating such photographic portraits, it is important to not see it as frozen in time. Consider this object's biography across generations and contexts; it takes on new meaning. Editor: Indeed. It prompts reflections of the individual, of technological changes in image-making, and in how these changes interact within the visual record.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.