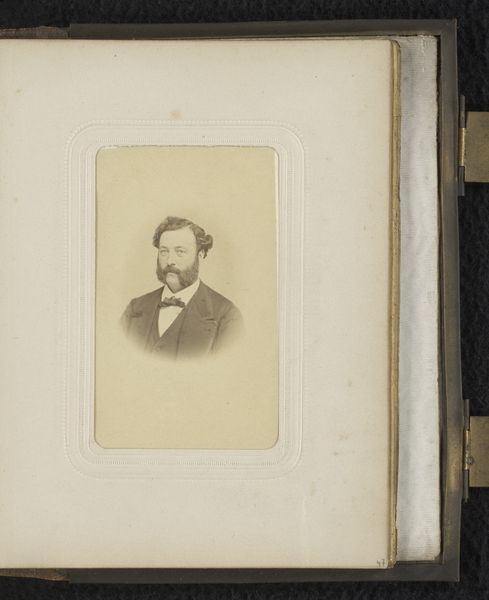

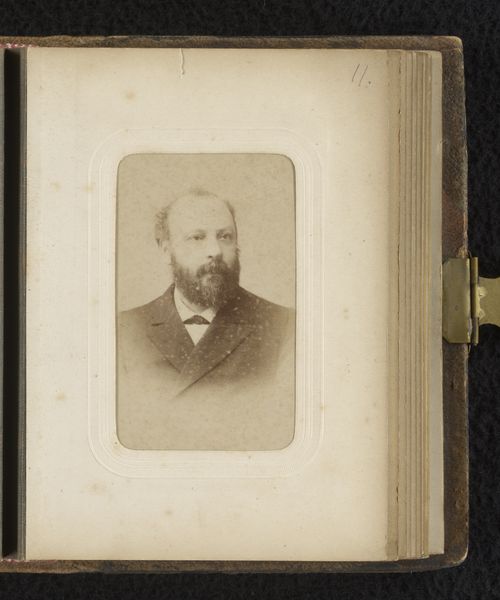

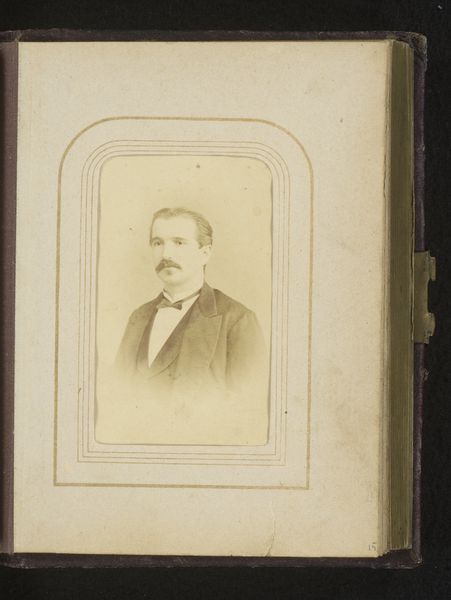

photography, albumen-print

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

muted colour palette

#

worn

#

photography

#

earthy tone

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 87 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

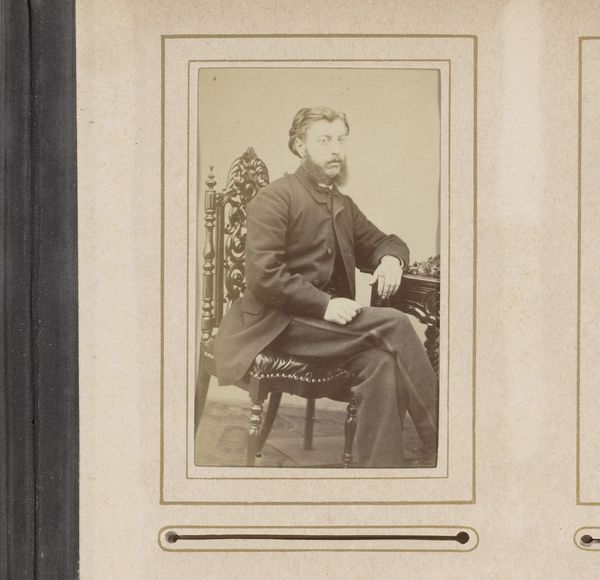

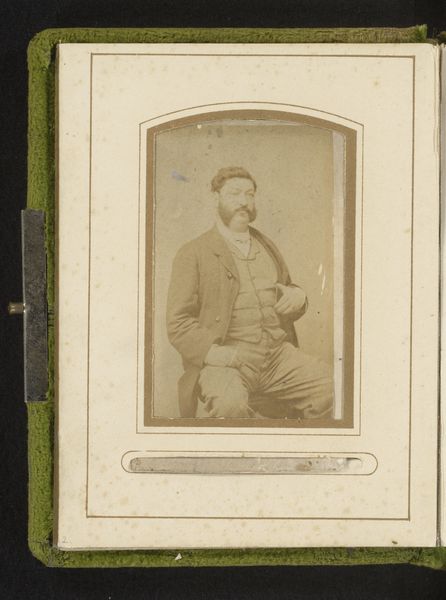

Curator: Editor: Here we have "Portrait of a Seated Man with Moustache and Beard" by Mayer & Pierson, dating from around 1855 to 1900. It's an albumen print, and I'm struck by how the warm, earthy tones and visible aging give it such a tangible, historical feel. What jumps out at you? Curator: I find myself drawn to the material reality of this object. Look at the albumen print itself; the process would have involved coating paper with egg whites, making it sensitive to light. This very deliberate act of preparation, of materially readying a surface, is critical. Then, there's the social context – who were Mayer & Pierson, and who was this sitter? Was photography democratizing portraiture at this time, extending representation beyond the traditionally wealthy? Editor: That’s a good point. I hadn't really thought about how the albumen printing process itself contributes to the artwork's meaning. So, it's not just the image, but also the layers of labor and material embedded in its creation that we should consider? Curator: Precisely. Consider the chemical processes, the craft of printing. Photography, especially at this time, was often seen as less artistic than painting or sculpture. By foregrounding the process, we can challenge these traditional hierarchies and recognize the skill and material intelligence involved. What kind of implications do you think are embedded with the subject's position and clothes, within that production environment? Editor: It gives another dimension. This wasn't just about capturing a likeness; it was about constructing an image of social standing, mediated through material choices – his suit, the chair. Maybe he worked with the photographer for this particular photograph? It almost seems as important as the figure and who he might be as a person. Curator: Indeed. We're no longer just passively viewing an image; we're actively engaging with the historical processes and the economic and social forces that shaped its creation. Editor: It's like the photograph itself is a record, not just of a man, but of the era’s social and material conditions. I hadn't thought about photography in such a material way before. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.