print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 109 mm, width 84 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

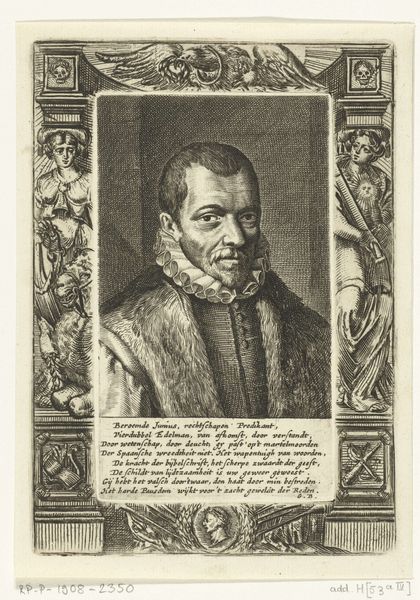

Editor: So, here we have "Portret van Gian Galeazzo Visconti," a print from between 1549 and 1575. It's this delicate engraving, very linear and detailed. I’m struck by how the artist has framed him almost like a saint. What story does this portrait tell you? Curator: The saintly presentation is telling. Consider the context. Gian Galeazzo Visconti was the first Duke of Milan, a hugely powerful and controversial figure in the 14th century. These portraits, especially much later engravings, weren't just about capturing a likeness. They were actively constructing, or perhaps more accurately, *re*constructing a historical narrative, even retroactively sanctifying his image. The angelic figures in the upper corners really reinforce that effort. Who was this portrait for? And what image of Visconti was it trying to cultivate? Editor: I see what you mean! It makes me wonder who commissioned this print, and for what purpose? Was it to legitimize a later claim to power, or perhaps to rehabilitate Visconti’s reputation? Curator: Precisely. Think about the institutions and social structures of the time. Genealogical claims to power mattered deeply. The Visconti family had a turbulent history. By circulating this image, they, or perhaps some other party with vested interests, were participating in a political act. Engravings like this played a critical role in shaping public memory. Note the chain, an obvious marker of wealth and therefore, power. Do you think this portrait flattered him, or simply projected authority? Editor: I think it projects authority above all else. It's interesting how something that seems like a straightforward portrait can be loaded with political meaning. Curator: Exactly. This reinforces that art is never truly neutral, and museums are key players. As spaces where images of political importance are circulated, preserved and framed for consumption. Editor: This was quite revealing! I will never look at historical portraits in the same light. Curator: That’s great. Recognizing the social life of images allows us to think more critically about whose stories get told and how.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.