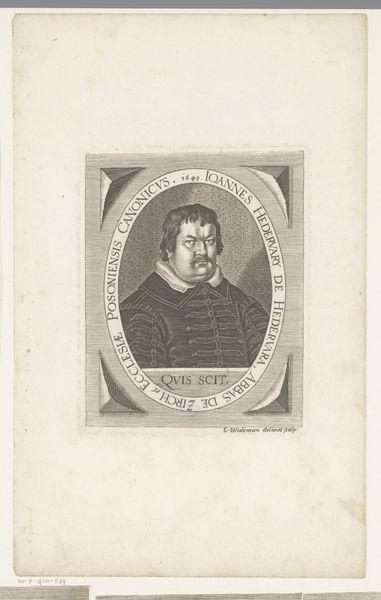

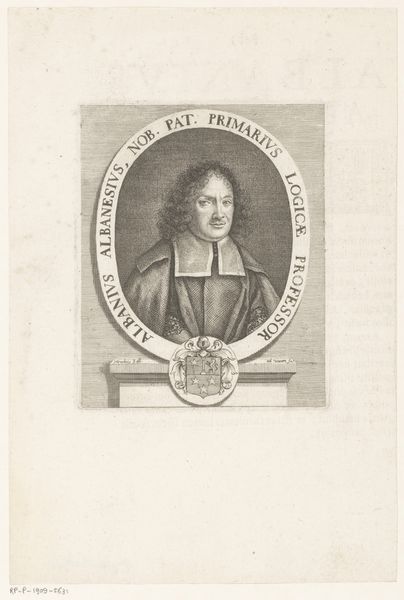

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

vanitas

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 148 mm, width 118 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Elias Widemann's "Portret van Hyacinth Macripodary" from 1651, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. It's an engraving on paper. Editor: The level of detail in the line work is incredible! The subject’s face appears so realistic within that decorative oval frame. I also notice "Omnia Vanitas" is inscribed at the bottom. What’s striking to you about this particular print? Curator: What grabs my attention is how this print functions within the economics of image production at the time. Consider the labor: the engraver's skill translating an image to a repeatable format. It was made to be reproduced, to circulate. Did Widemann engrave it himself or was he profiting from other people’s labour? Also, who consumed such images and why? Editor: That's interesting, the consumer aspect isn't something I would have considered immediately. I guess portraits were always commissioned, but were prints made more available? Curator: Precisely! The Baroque period witnessed a flourishing print market, allowing for wider dissemination of images and ideas beyond the elite. Engravings like these made portraiture accessible. How does the idea of "Vanitas" function in making it commercially available? Editor: So the ‘vanitas’ theme suggests that worldly achievements are fleeting, and combining that with a portrait, it becomes a contemplation on the subject's life and legacy... available for purchase? It adds a layer of complexity. I hadn't thought about it as a commodity. Curator: Exactly. Think about the social and economic function of such a work beyond simply artistic expression. It speaks to power, to patronage, but also to the democratizing potential inherent in the printmaking process itself. How do you see the implications in contemporary culture? Editor: It’s definitely changed my view! The print isn't just a portrait; it’s an object embedded in a web of production, distribution, and consumption. It's fascinating how those material processes shape its meaning. Curator: Indeed. And recognizing that interplay allows us a richer understanding of not just this work, but the broader social context in which it was created and continues to exist.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.