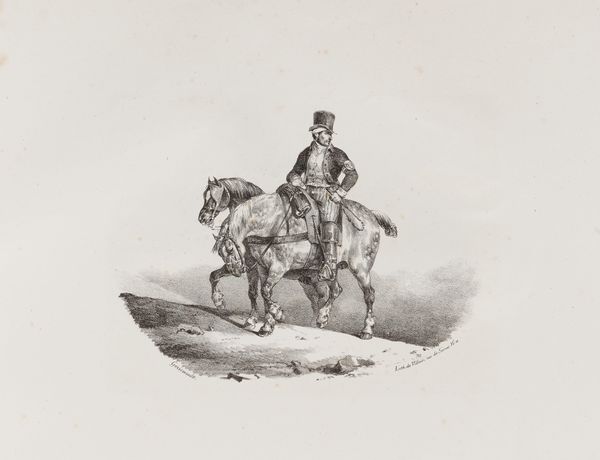

drawing, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

orientalism

#

graphite

#

islamic-art

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

realism

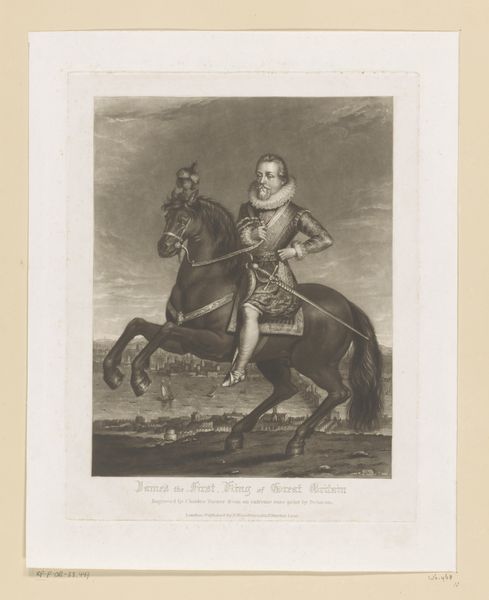

Dimensions: height 382 mm, width 279 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

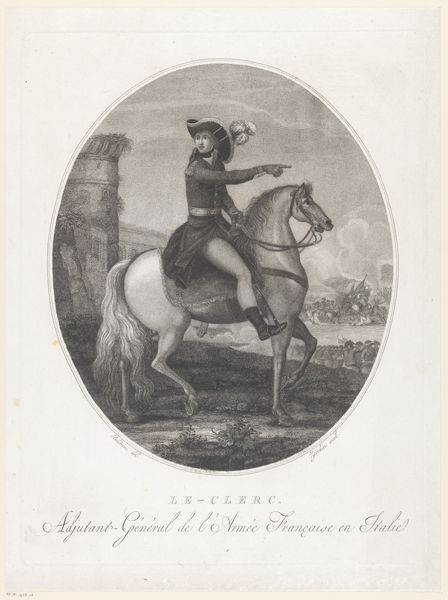

Curator: This drawing offers an intriguing glimpse into 19th-century Egypt. It's titled "Ruiterportret van Mohamed Ali van Egypte," dating between 1819 and 1851, attributed to Karl Loeillot-Hartwig, and made with graphite. Editor: It’s remarkable. I'm immediately drawn to the precision of the lines, especially in rendering the horse's musculature and the fine detail in the rider's attire. There is great attention given to texture. What sort of paper or ground was used? Curator: Considering it is graphite, I agree, the layering to achieve such definition must have been demanding. Beyond the technical skill involved, consider the historical weight of this image. Mohamed Ali was, to put it mildly, a transformative figure. How does the medium, graphite on paper, shape our understanding of the representation and circulation of power in the context of Egypt and Europe? Editor: That's a keen question. Graphite allows for the creation of multiples, and engravings enabled wide distribution of imagery. Was this image initially made for a patron, or produced and circulated through printmaking for the wider European market eager for images from afar? And was this portrait designed to be a propaganda tool? I'm particularly curious how Loeillot-Hartwig accessed this image and the political context. Curator: Your point about its function as propaganda resonates. Ali's modernization efforts were indeed multifaceted, encompassing military reform, industrialization, and cultural exchange, so a potent and impressive image was very effective. His ambition fueled expansionist policies which ultimately conflicted with Ottoman and European interests. How would the materials used have impacted distribution costs and, consequently, how many could have accessed such an image? Editor: So it may well be a question of scale, how that informs the power structure, even now. Its relatively intimate nature suggests, perhaps, a limited audience. Still, this does allow us to delve into issues of material access and the visual construction of leadership. And even reflect on its lasting appeal, from those immediate networks and up to contemporary contexts now as well. Curator: Indeed. These subtleties, revealed through the image, bring so much of the history to light. The dialogue really does create another layer to view and better interpret not just this singular artwork, but its ripple effect throughout all of this time. Editor: Precisely, it encourages us to look deeper.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.