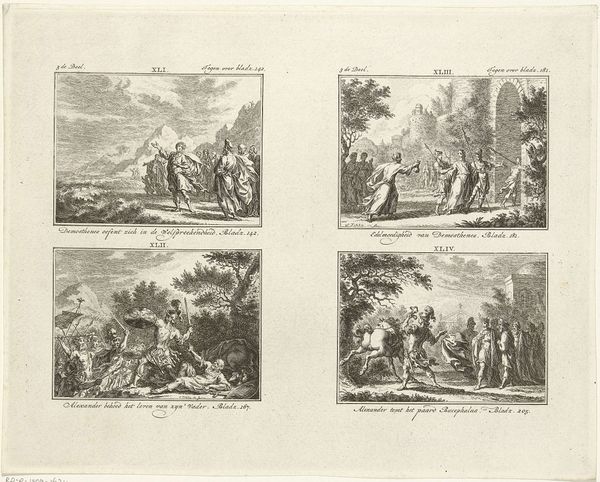

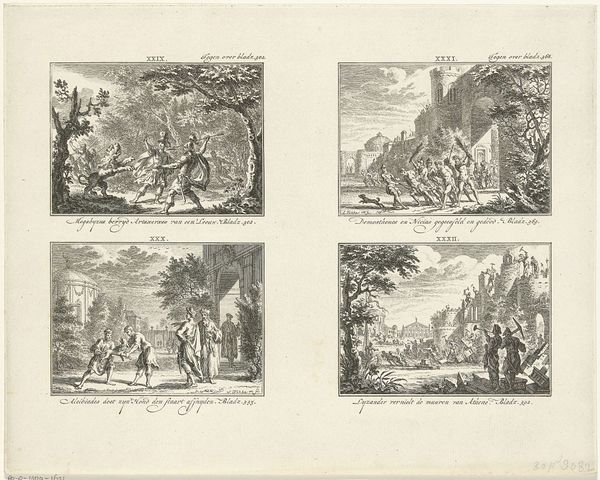

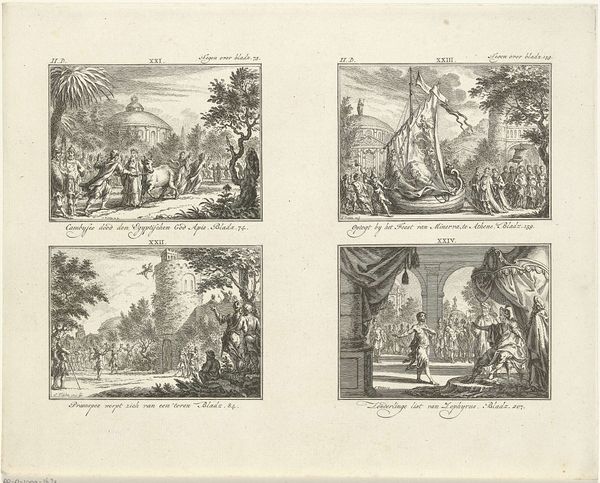

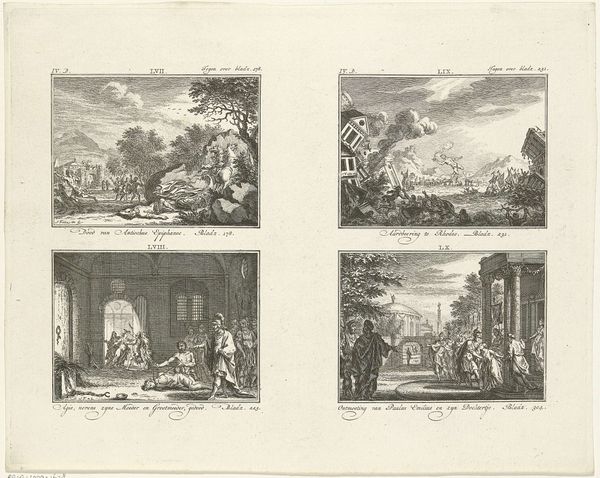

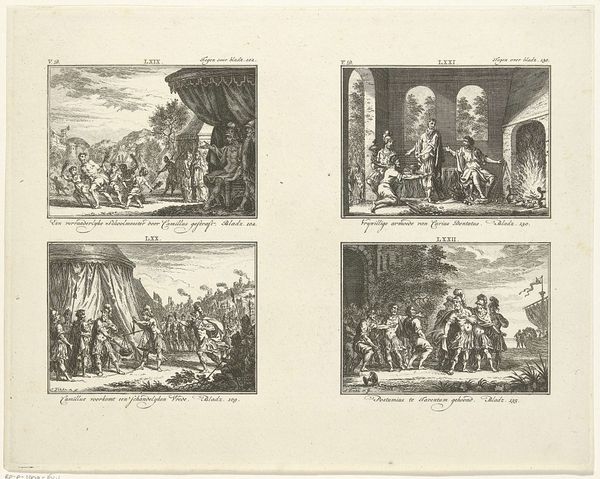

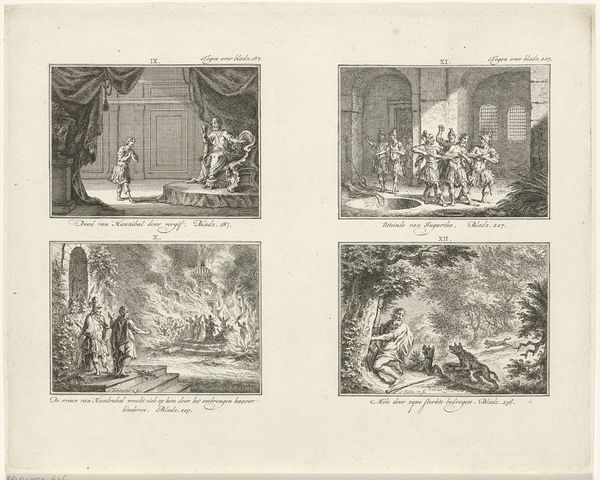

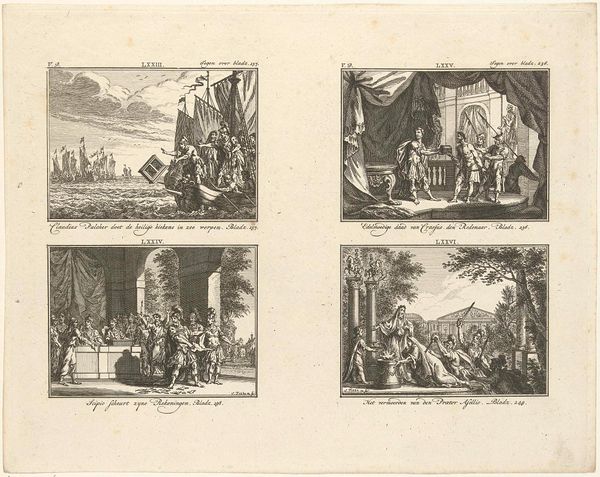

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 222 mm, width 282 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, "Four Scenes from Classical History" by Simon Fokke, dating from between 1722 and 1784, presents miniature narratives in a baroque style. What strikes you initially? Editor: I'm drawn to the intricacy of the lines, the density of detail he’s achieved with what I imagine are simple tools. How was something like this made, and what does it tell us about the period’s priorities? Curator: The material production is paramount. Engraving, as a printmaking process, allows for dissemination. What does it signify to produce classical scenes using this technique, and to what extent were these images used for educational purposes, political messaging or decorative applications by a broader audience, not necessarily among elite patrons? Think about the physical act of engraving – the labour involved, the repetitive actions... does that inform your understanding of the narratives? Editor: So, the *how* of it is vital. Was engraving viewed as 'lesser' than painting, and did this accessibility challenge established hierarchies in art? The mass production... almost democratizes these stories. Curator: Precisely. It challenges our modern perception of originality and value. Who controlled the narrative and the visual consumption during this period? These weren’t unique artworks meant to adorn the walls of aristocrats. Think about the materials themselves - copperplate, ink, paper – relatively inexpensive compared to the canvas and oils of a painting. It is worth asking how those things might be connected. Does this affect the way we interpret the stories presented here? Editor: It does shift the focus. I’m now wondering who the intended audience *really* was, and what they took away from seeing these scenes replicated and distributed widely. Was it pure moral instruction, or something more complex? Curator: Indeed. Consider also, how does the reproducible nature of engraving influence how these "historical" images are understood and believed? Did this make the image more impactful? The image’s portability and broad distribution changed its function and consumption. What's your overall takeaway from considering the engraving through a materialist lens? Editor: It reframes my understanding. The artwork’s inherent value now is deeply entangled with its social life and production and I hadn't considered the full implications of 'print' before. It seems it wasn't just about depicting history, but *making* history accessible, perhaps even re-writing it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.