Copyright: Public domain

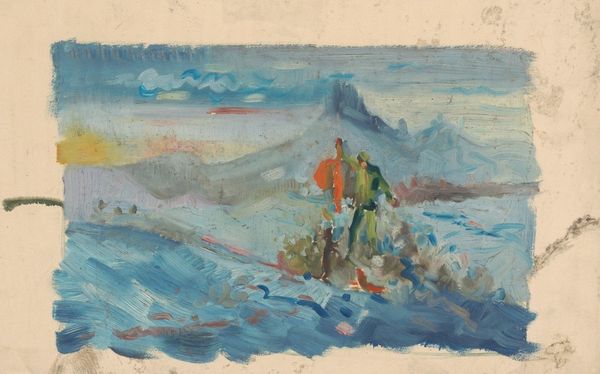

Editor: Here we have Edgar Degas' "Lake and Mountains," created in 1893 using oil paint and watercolor. It’s quite dreamlike, almost like a memory of a landscape rather than a realistic depiction. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a fascinating negotiation with the male-dominated landscape tradition of the 19th century. Degas, primarily known for his depictions of women, particularly ballerinas, here engages with a genre often associated with assertions of power and control over nature, usually through a masculine lens. Notice how the colors are muted, almost melancholic, devoid of the typical bravado you'd find in, say, a Bierstadt. What do you make of that? Editor: That’s interesting! So the lack of vivid colors could be a deliberate subversion of that power dynamic? Curator: Exactly! Think about the social context: the rise of industrialization, the changing roles of women, the anxieties surrounding modernity. Degas, consciously or not, seems to be questioning traditional hierarchies through this delicate rendering. The ambiguity of the landscape, its lack of precise detail, further underscores this resistance to fixed, patriarchal perspectives. Where do you think it sits within his other, more figurative work? Editor: I suppose compared to his paintings of dancers, it seems less observational and more introspective, as if he’s turning away from societal performance towards something more personal. I hadn’t considered its connection to the power structures of landscape painting before! Curator: And perhaps reflecting his own positioning within those societal structures. Considering identity, how might we interpret this through the lens of class? What opportunities were available to him and, equally, unavailable to those not sharing his privileges? This landscape then transforms into a stage upon which we examine social and gender dynamics. Editor: That's a really interesting angle; I'll definitely think about that when I look at landscape paintings from now on. Thanks! Curator: My pleasure. It's through these kinds of dialogues that we breathe new life into art history and make it relevant to today's conversations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.