drawing, paper, ink, charcoal

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

Copyright: Public Domain

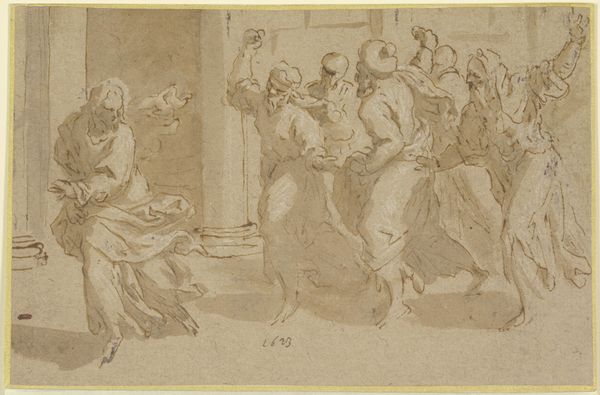

Curator: This compelling drawing, held here at the Städel Museum, is titled "The Pharisees and the Adulteress," attributed to Palma il Giovane. It's rendered in ink and charcoal on paper. What are your initial impressions? Editor: The composition immediately strikes me. The way the figures are clustered creates a palpable sense of tension and accusation, but rendered with a surprisingly subdued palette, almost as if muting the dramatic scene. Curator: Yes, and Palma's use of line and shadow are crucial to understanding this scene. Consider the sharp, almost angular lines of the Pharisees versus the softer, more flowing lines that define the woman's form. Could it represent a duality or even bias in interpretation? Editor: Precisely. The Pharisees, with their rigid postures, are clearly defined, projecting an almost impenetrable self-righteousness. But her very form, seemingly collapsing in on itself, it tells its own cultural narrative of female shame. The visual language becomes a reflection of the socio-political power dynamics at play. Curator: Also consider the religious context. The story itself – Jesus challenging the Pharisees to cast the first stone if they are without sin – is a powerful lesson in hypocrisy and mercy. This, represented, echoes the human struggle with inner integrity and outwardly accepted ideals. Editor: Indeed, it reflects a turning point within religious thought—the questioning of established hierarchies of sin. Furthermore, where would you place this drawing historically in relationship to public religious belief? Is this piece actively engaging the artistic depictions before, or against? Curator: That is exactly it—this era was really about the challenge of human perception. The academic approach with some style and even movement is engaging those very traditional constraints and perceptions, yes. Palma’s perspective offers a reinterpretation that challenges those doctrines. Editor: Thinking of the historical forces that affected the artist—and through the artist the people around—helps me really frame not just the art, but its context, and how that impacts future thought. Curator: I completely agree; seeing those symbols and influences over centuries highlights our evolving engagement with complex ideas like justice, piety, and human compassion. Editor: It gives the drawing a contemporary resonance as we continuously debate those societal expectations. Curator: Exactly. Perhaps an image can allow for the constant cycle of question and exploration and understanding of morality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.