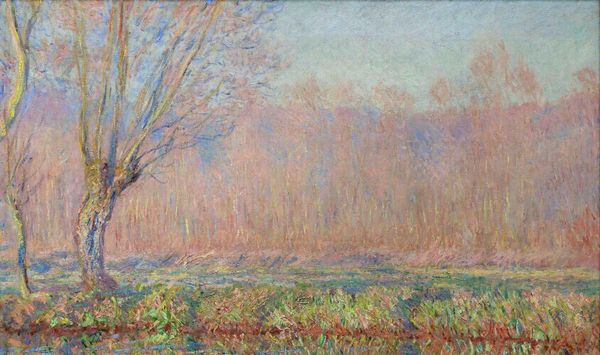

Copyright: Public domain

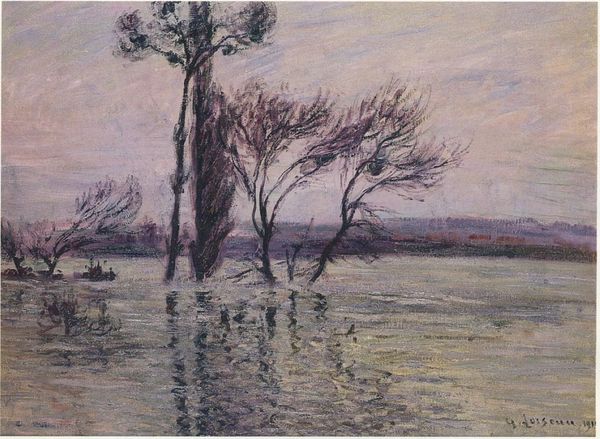

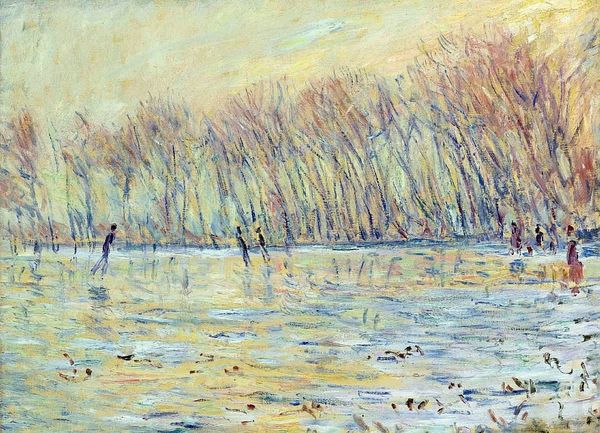

Editor: We’re looking at Claude Monet's “Flood Waters” from 1896, an oil painting. The overall effect is muted, a little unsettling, with those bare trees standing in the water. What do you see in this piece, beyond the surface depiction? Curator: It's crucial to consider the social context and the physical reality of painting en plein air at this time. Monet wasn't just capturing a scene; he was engaging with the materials available, the increasing industrialization providing ready-made paints in tubes, and the evolving role of labor in art production. Note how the brushstrokes themselves become part of the narrative, each dab and stroke evidence of the physical act of painting and its reproducibility. The way he’s physically moved paint around. It mirrors labor. Editor: Reproducibility? Can you elaborate? Curator: Think about the rise of the art market. Impressionism coincided with developments in printmaking, photography, and increased art viewership, and access. This painting is made using readily available oil paints in a plein-air style - a technique which depended upon the invention and availability of portable easels and paint tubes. He is one piece of a giant economic-industrial puzzle. Editor: That's a completely different way of seeing it. I was caught up in the aesthetic qualities of Impressionism, but I get what you’re saying about its means of production as also its message. Curator: Exactly. We tend to valorize the "artistic genius," but what about the availability of materials and how social and economical forces are impacting the creation of an artist’s legacy? Editor: That’s given me a lot to think about! It really shows how deeply interwoven art and society can be.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.