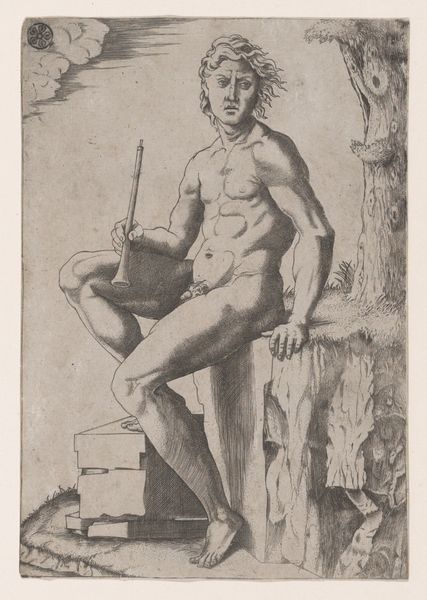

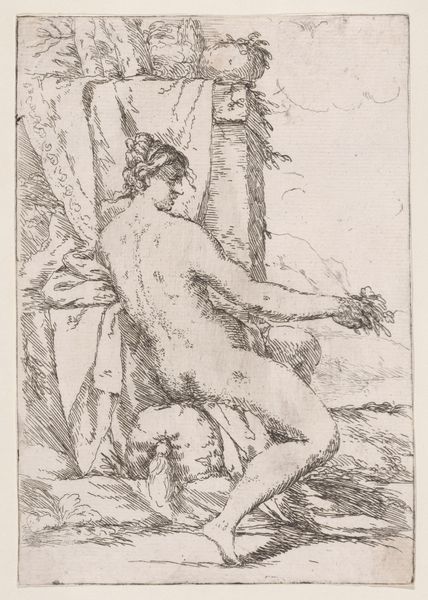

Judith, looking towards the right, seated nude atop the dead body of Holofernes, with a sword in her right hand and the head of Holofernes in her left hand 1525

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

death

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

#

sword

#

miniature

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 1/8 x 1 7/16 in. (5.4 x 3.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

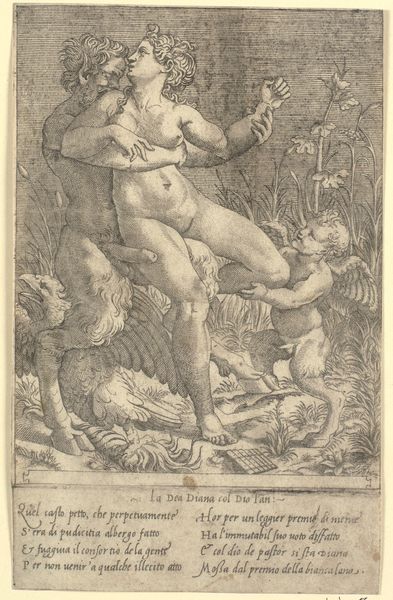

Editor: This is Barthel Beham’s “Judith, looking towards the right, seated nude atop the dead body of Holofernes, with a sword in her right hand and the head of Holofernes in her left hand,” created as an engraving in 1525. It’s… surprisingly unemotional. Given the graphic subject matter, Judith’s almost placid expression is startling. How do you interpret this work, especially its apparent lack of drama? Curator: It’s vital to consider the historical lens here. The story of Judith, a Jewish widow who saves her people by seducing and then beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes, was frequently used during the Renaissance. How might that context challenge our contemporary expectations of the “heroic”? Editor: I guess I always saw Judith as this righteous figure, a brave woman striking a blow against tyranny. But in this image, there's an unsettling coolness, especially given she's nude and seated on a decapitated body. Curator: Exactly. Consider the prevailing attitudes towards women, power, and sexuality in the 16th century. How might Beham’s portrayal of Judith reflect or even subvert those societal norms? Perhaps it's a commentary on female agency and its perceived dangers. Or perhaps this engraving flattens Judith into a trope, turning a moment of resistance into spectacle? The meaning shifts again if you think of it as a "miniature" which some have called it; do intimate spaces then further amplify the act of sexual and gender transgression that Judith embodied? Editor: That’s really interesting. Seeing it as less of a celebration of female empowerment and more of a… complicated statement about it makes so much sense. I didn't even realize I was bringing my 21st-century feminist lens to this Renaissance print. Curator: And that’s the beauty of engaging with art history, isn’t it? It forces us to confront our own biases and to continually re-evaluate our understanding of both the past and the present. Editor: Definitely. I’m now seeing how this isn’t just a straightforward retelling of a biblical story, but a complex dialogue on power, gender, and societal expectations of its time. Curator: And hopefully also, how those dialogues can carry over to current questions!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.