drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

#

realism

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

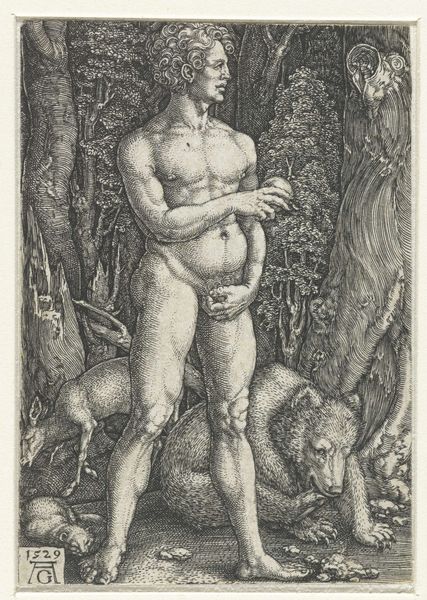

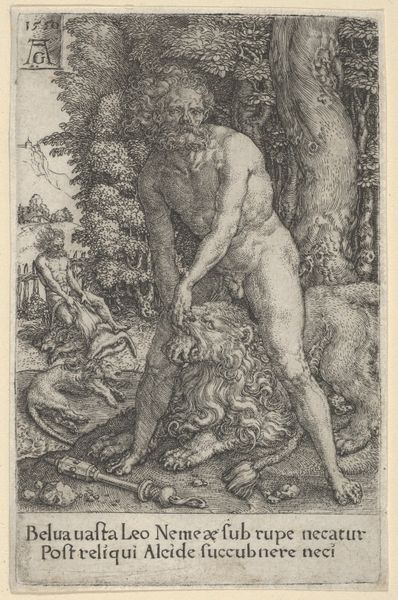

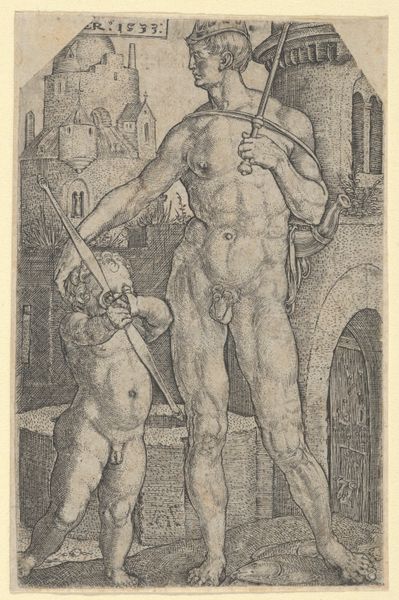

Curator: This engraving by Sebald Beham is titled "Adam Standing" and dates back to 1524. It's an intriguing piece, isn't it? Editor: Yes, immediately I’m struck by how grounded it feels, almost earthy, despite the traditional subject matter. The texture created through the engraving process really brings out the material quality of everything depicted—the tree, the snake, even Adam's skin. Curator: Indeed. Beham, a prominent figure in the German Renaissance, was part of a group of artists known as the Little Masters, renowned for their small, detailed prints. The circulation of prints like these played a huge role in spreading knowledge and artistic styles throughout Europe at the time. It allowed a broader audience to engage with art and ideas. Editor: And you can see the influence in the mark-making, in the almost obsessive detail given to the rendering of surfaces. Notice the hatching and cross-hatching – Beham coaxes an astonishing range of tones out of a purely linear technique. That’s also how class distinctions became evident. Access to artworks depended upon financial standing in society. Curator: Exactly. He was a master of the line. But think about what this image represents. It’s Adam, post-fall, holding the apple. Beside him, is it a calf? The snake's draped unnaturally around his arm... It challenges the viewer, doesn't it? The date prominently displayed asserts the creation of this interpretation, and perhaps implicitly, its validity as a narrative worth dissemination. Editor: It makes me think about the workshop practices of the time. The sheer labor involved in producing these engravings! Think of the specialized tools, the apprenticeship system, and the social structures that supported this kind of production. It also leads one to consider issues such as where the metal came from and where Beham acquired his mastery of the medium, and how his skills were shaped by both individual practice and collaborative knowledge. Curator: Absolutely. The context is critical, too. The Reformation was in full swing, and images, particularly religious ones, were being scrutinized and often condemned. Beham himself was known for his unconventional interpretations of biblical subjects. The power structures were disrupted. What's so fascinating is the role of printmaking as a tool of dissent. Editor: A lot to digest about labor, distribution of wealth, and even religion and politics, conveyed through skillful applications of a simple metal plate. It emphasizes how what might seem like just an exercise in skilled artisanship reflects some of the bigger social concerns of the time. Curator: Well said. It certainly gives one a richer perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.