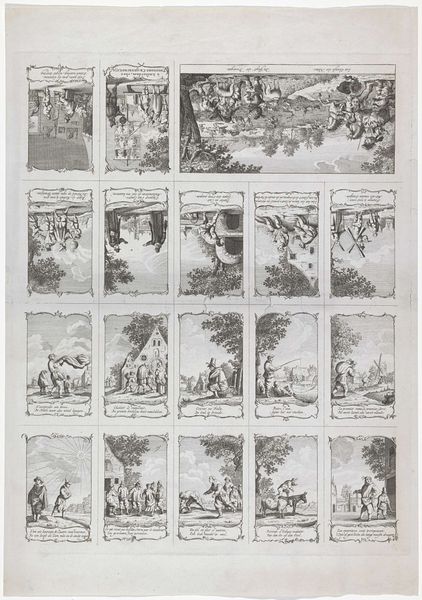

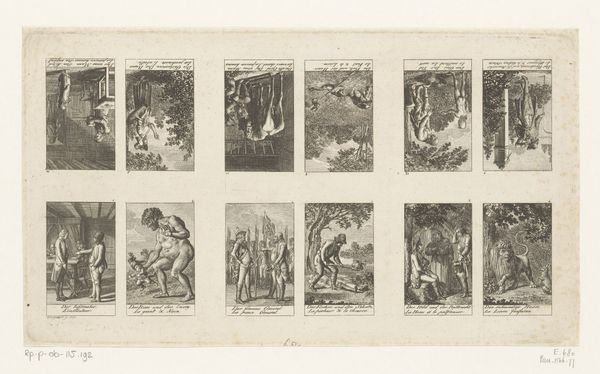

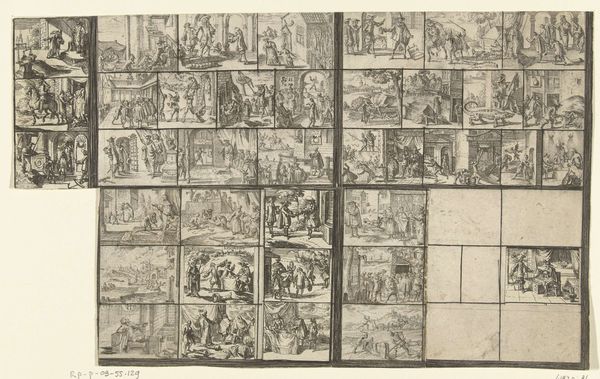

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 414 mm, width 491 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is a print titled "The Twelve Months," dating back to 1687, a fascinating example of late Baroque artistry from an anonymous creator, residing here at the Rijksmuseum. It is created as an engraving. Editor: At first glance, it’s almost like a visual calendar, sectioned into miniature worlds. Each seems steeped in symbolism and rendered in incredibly precise detail despite its overall size, a mood akin to illustrated fairy tales and folk customs, wouldn’t you agree? Curator: Indeed, it offers a snapshot into the societal understanding of time and labor, wouldn’t you agree? Think about how the concept of distinct seasonal tasks intersects with early capitalist structures and how the print engages themes central to Dutch society at the time such as agriculture and community life. The engravings give life to agricultural labour with classical imagery. Editor: Right, and consider how this plays into an established tradition of representing time through allegorical figures. Each scene, named meticulously at its base, is rendered in distinct tones to express its individual sentiment, though the use of similar backgrounds unites them all. It’s interesting to consider the emotional weight carried by such iconic figures. Curator: Precisely! It also begs a crucial question about its initial function. Was it intended for an elite audience, meant to illustrate social ideals and hierarchies, or did it address broader social layers to show everyone’s work, lives, and places during the circle of time? Such artworks served to instruct moral virtues while also shaping perspectives on power dynamics and the accepted order. Editor: From a purely iconographic view, look at "July"—she holds what appears to be harvested wheat and an empty bag in an attitude that mirrors classical depictions of fertility or abundance—images that would resonate deeply and culturally. Similarly, we can reflect upon this composition as a set of totems through a shared collective visual memory! Curator: The layering of time, class, labor, and visual rhetoric is rich enough to offer a complex image of 17th-century Dutch experience, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: Certainly. Ultimately, it asks how deeply ingrained cultural representations can reveal much of the society that produced them and that these iconic representations stay with us, to the present day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.