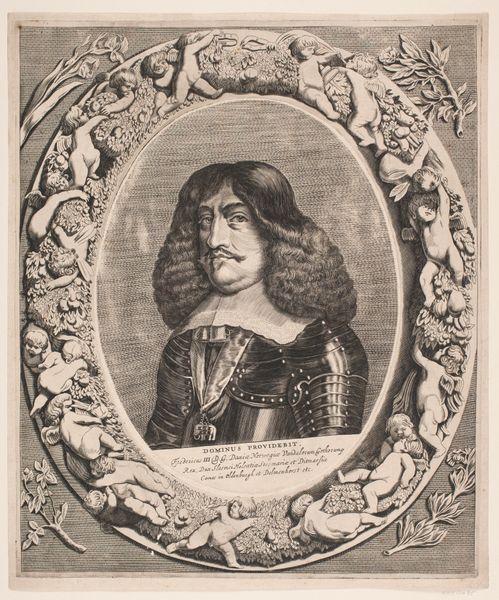

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 155 mm (height) x 120 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: This is "Ove Skade," a 1666 engraving by Albert Haelwegh, part of the collection at the SMK, Statens Museum for Kunst. What’s your initial read? Editor: Stark, precise. The contrast of the lines etched into the paper almost feels like the pressure of the subject's status being imprinted onto a material reality. Curator: Indeed, and notice the baroque framing device. It lends the piece an almost theatrical quality. Within, we see the somber gentleman, but it is framed within a very decorative border—perhaps alluding to the trappings of power and persona. Editor: It’s fascinating how the image is physically produced: an engraving created through the deliberate labor of the artist manipulating a metal plate, transferred through pressure. It gives such a different weight than, say, a painting of a noble from the same time. What message might the use of such a process communicate? Curator: Engravings often democratized imagery—more replicable than paintings, spreading portraits like this to a wider audience. So it reinforces this tension: a portrait, inherently an image of power and perhaps hubris, circulated by a mode of production making it less unique, less aristocratic. The latin inscription also becomes a powerful attribute. Editor: Yes, and in his gaze, do you detect the confidence expected of his position? It’s faint, maybe worn down by history. I’m thinking about the labor embedded in this engraving and wondering who produced the paper it’s printed on, what those processes looked like. Curator: That material consideration truly adds another dimension. Consider the intended viewers – those able to decode not just the visual cues, but the textual layers, too, and their historical circumstances. A portrait that demands interpretation from learned readers in particular! Editor: Ultimately, Haelwegh's careful manipulation of materials serves as both a representation and a product of its historical and social forces. Curator: Absolutely. These portraits provide glimpses into cultural memory rendered through line and labor. Editor: Yes, reminding us that even portraits of privilege have to come down to the earth, literally, to find a material foothold to enter the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.