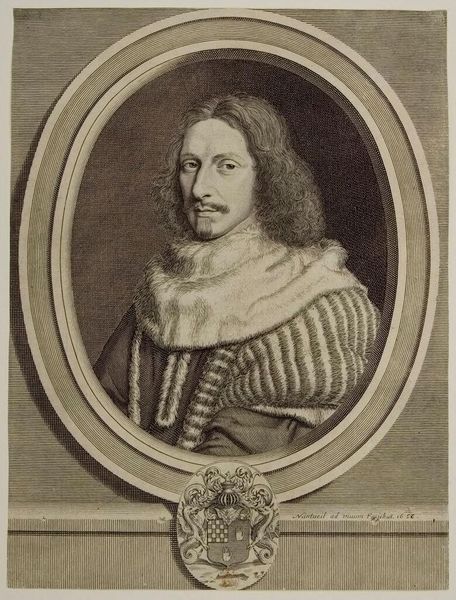

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: 92 mm (height) x 77 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Editor: This engraving, "Ove Skade," was created in 1666 by Albert Haelwegh, currently residing at the SMK. The texture achieved through these delicate lines is remarkable. How can we think about this piece? Curator: Consider the process, Editor. Engraving in the 17th century wasn't merely about representation, it was a form of cultural production tied to specific social structures. Who would commission a print like this, and for what purpose? Editor: Well, the sitter appears to be someone of status, given his clothing and that impressive chain. Was this a common form of portraiture at the time? Curator: Absolutely. Prints democratized portraiture to some extent. While an oil painting was costly, engravings allowed for wider distribution. This opens avenues into considering material access to representation and knowledge at that time. The means of producing and disseminating imagery was changing rapidly. Editor: So, we can see this as an early form of mass media? Curator: In a sense, yes. Reflect on the labour involved - the engraver, the printer, the distributors. And think about how these images functioned in society. Were they traded? Collected? Used for propaganda? Each print is not just an image of a man but a complex web of social and material relations. Editor: I hadn't considered the economic aspects so deeply. It makes the portrait more than just a likeness. Curator: Precisely. The materials, the tools, the labor... they all contribute to the meaning. We can trace a commodity chain from the engraver’s workshop to the collector's album, understanding the value and use of the portrait at each stage. Editor: Thanks. I now understand this piece, and others like it, with a widened appreciation for all the forces that factored into its creation and use.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.