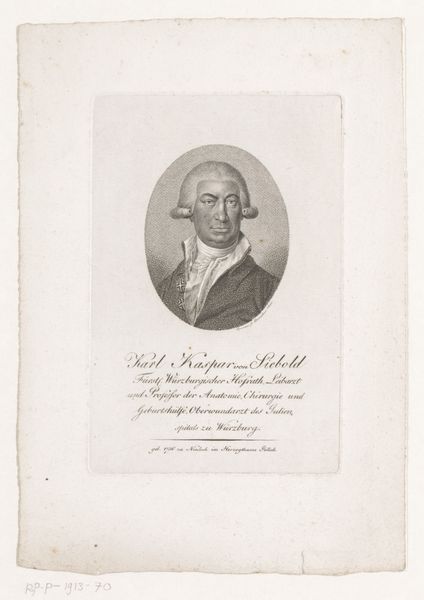

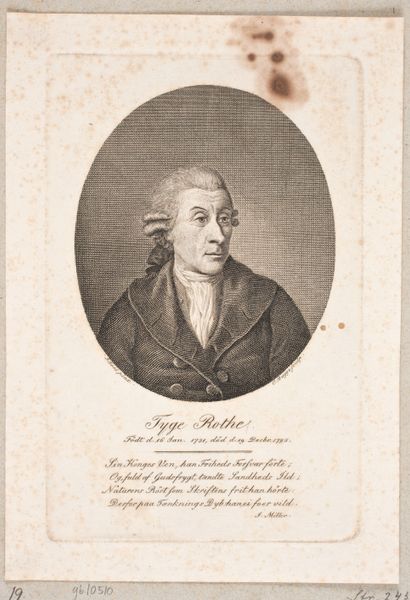

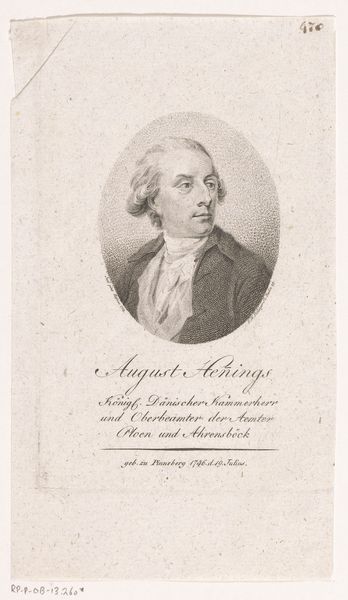

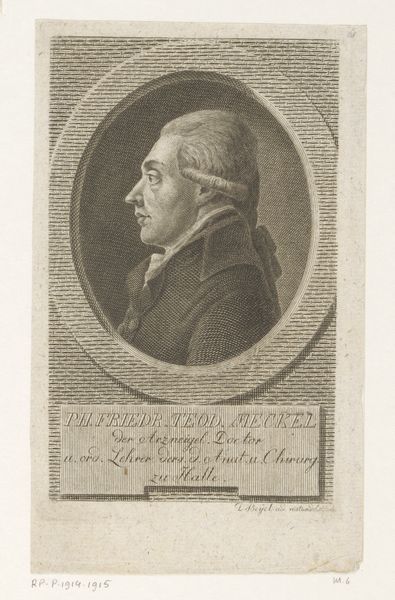

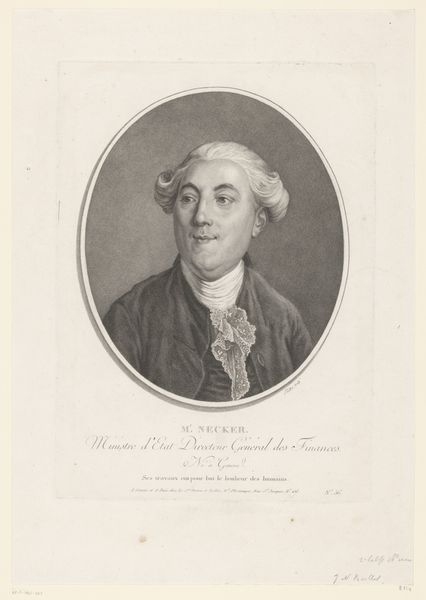

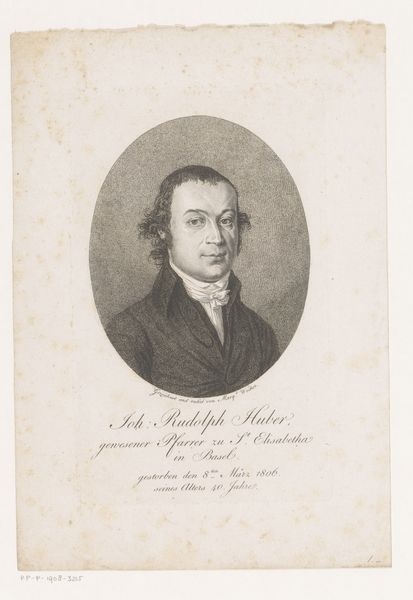

print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

yellowing background

#

photo restoration

# print

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 163 mm, width 113 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We are looking at an engraving identified as “Portret van Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland,” dating approximately from 1801 to 1825. Editor: My first thought is how delicately it captures the sitter. The fine lines and oval frame create a sense of intimacy. Curator: This portrait, created on paper, demonstrates the detailed process involved in engraving, from the initial drawing to the carving of the image onto a metal plate, and ultimately, the printing itself. Consider the labor involved. Editor: And within that labor, there's a clear statement being made. Hufeland, as evidenced by the inscription below the portrait, was a prominent figure. Royal Privy Councilor, personal physician, a director and member of academies. This portrait immortalizes his position within a very structured societal framework. Curator: Yes, and it’s worth considering the accessibility of printmaking during this period. Engravings allowed for wider distribution of portraits, contributing to the construction of public image and perhaps even a sort of brand for figures like Hufeland. Editor: The dissemination of his image is important, particularly given his profession. Hufeland was an influential physician who advocated for preventative medicine. Consider how this image could reinforce his authority and spread his ideas on public health and hygiene, reaching beyond the elite circles. Curator: Precisely! Think about the materiality too. The paper itself—its quality and how it ages— speaks to the history of the object and its conservation over time. Its survival and preservation contributes to this historical understanding. Editor: Absolutely. The portrait functions as more than just an image. It embodies the intersecting forces of power, health, and social identity in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Curator: Examining the processes, the tangible nature of this artwork emphasizes printmaking’s significance. Editor: Considering the sitter's role and the portrait's place in broader conversations shows how the seemingly simple lines carry deep context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.