Dimensions: height 290 mm, width 204 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

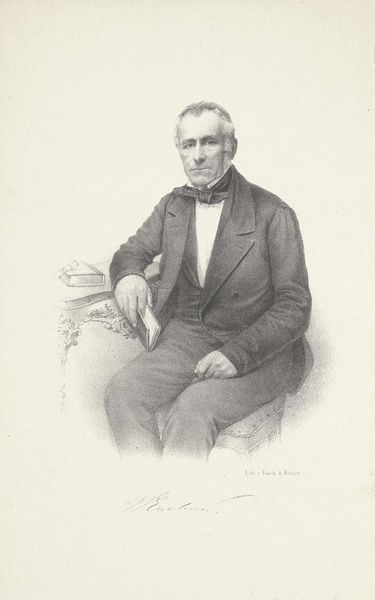

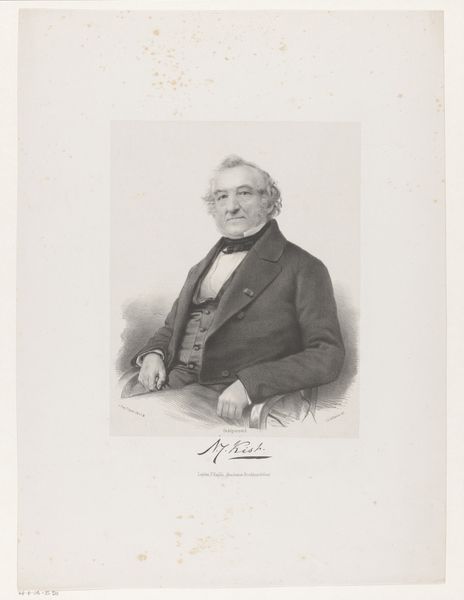

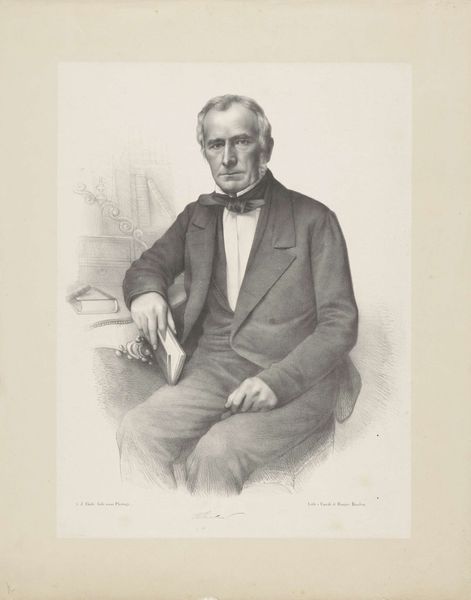

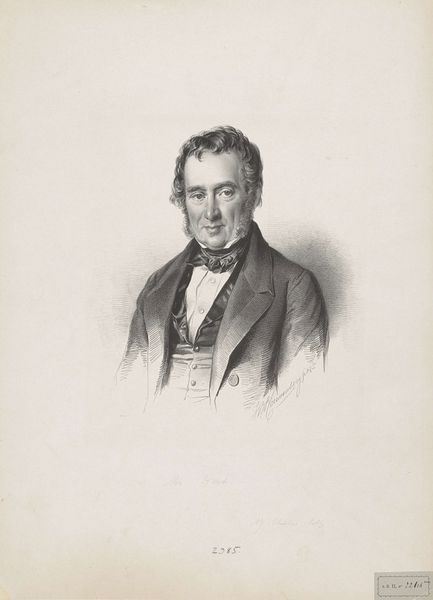

Curator: Welcome. We are standing before Edouard Taurel’s "Portret van Andreas Schelfhout," made in 1867. This drawing, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum, utilizes pencil and engraving to depict the Dutch landscape painter. Editor: My initial impression is of stark elegance. The controlled pencil work gives a beautiful range of greys that suggests the fine detail and dignity of Schelfhout, softened somewhat by the artistic flourishes of Romanticism. Curator: Indeed. It’s interesting how Taurel, working during a period of increasing industrialization and urbanization, chooses to portray Schelfhout, a celebrated painter of quintessentially Dutch landscapes. There is an engagement in this choice with idealized notions of nature and nationhood, against a backdrop of socio-economic change. Editor: I am intrigued by the process behind this print. The initial pencil drawing, carefully rendered to capture Schelfhout’s likeness and then translated into an engraving—that transition suggests a mechanical reproduction, and questions of authorship come into play. To whom does this image belong: Taurel the draughtsman, the engraver, or Schelfhout himself? Curator: Absolutely. The act of reproduction democratizes the image. Prints made art more accessible, spreading Schelfhout's likeness—and by extension, his artistic brand—to a wider audience. Editor: There is also the detail of the hands clasped over what looks like a book or a portfolio. It speaks to his intellectual or artistic labor, placing value on his work and craft. I wonder if the choice of this pose, and even the engraver’s skillful rendering of it, was aimed to solidify a respectable artistic identity in an era when traditional notions of labor were challenged? Curator: Good point. Artists sought validation in a changing social order. The emerging art market needed to present artists as respectable professionals to maintain the art's cultural value. Schelfhout isn’t merely a painter but is shown as a man of substance and learning. Editor: Looking closer, there is the slight awkwardness of the pose, perhaps even a hint of caricature, as some suggest. But does this then undermine the subject’s integrity? Does it unintentionally betray something else beneath the facade of his esteemed portrait? Curator: Possibly. However, in 1867, the concept of "realism" in art became increasingly celebrated for its frank portrayal of individuals and subjects, embracing minor imperfections instead of aiming for strict idealization. Editor: I leave this viewing with a question, a better sense of the labor, skill and reproduction invested in creating and circulating imagery in the 19th century. Curator: I see the fascinating dialogue between tradition and change embedded in the image itself; between a man defined by the natural landscape and its portrayal disseminated widely through innovative technology.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.