drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

ink paper printed

#

pen sketch

#

hand drawn type

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

intimism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

ink colored

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

sketchbook art

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

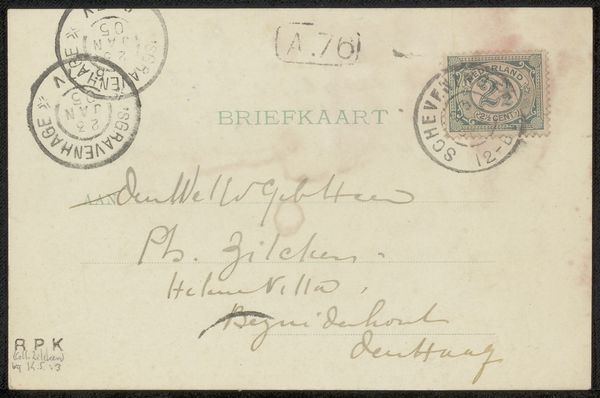

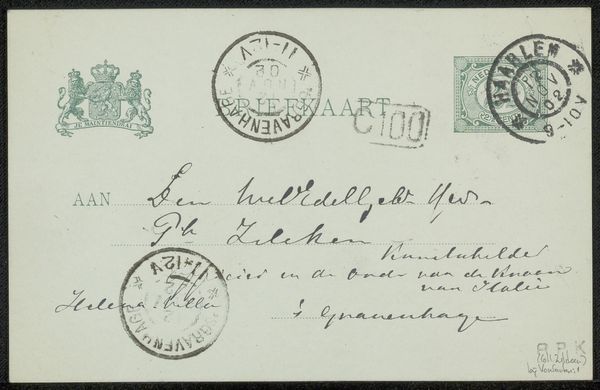

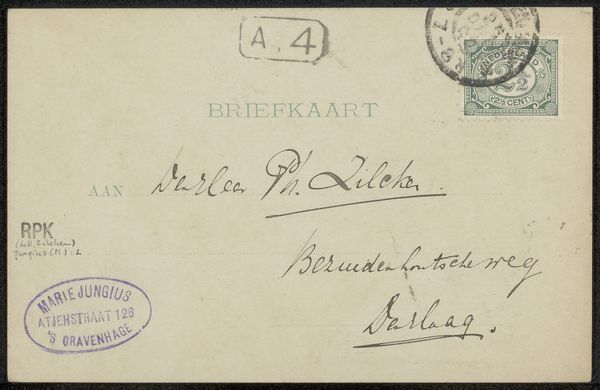

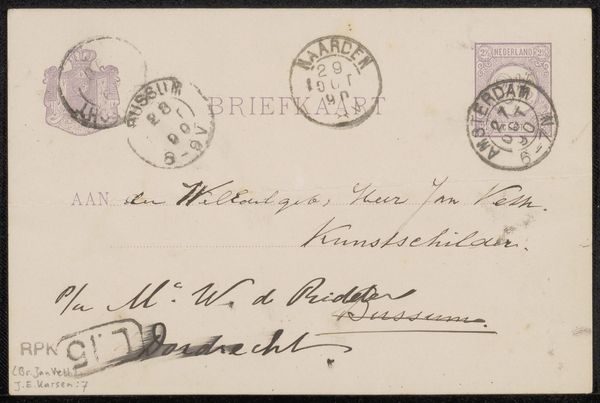

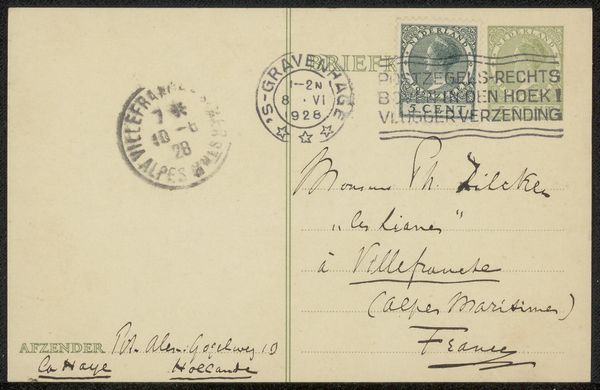

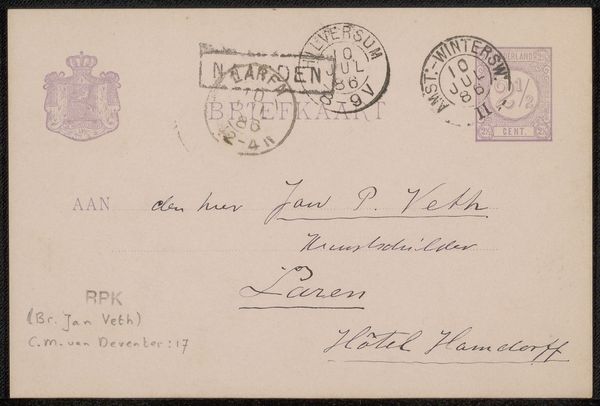

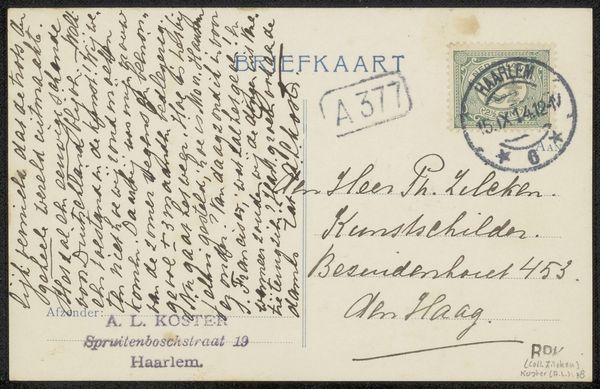

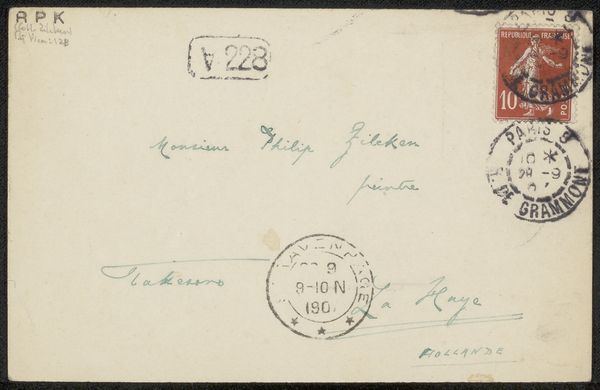

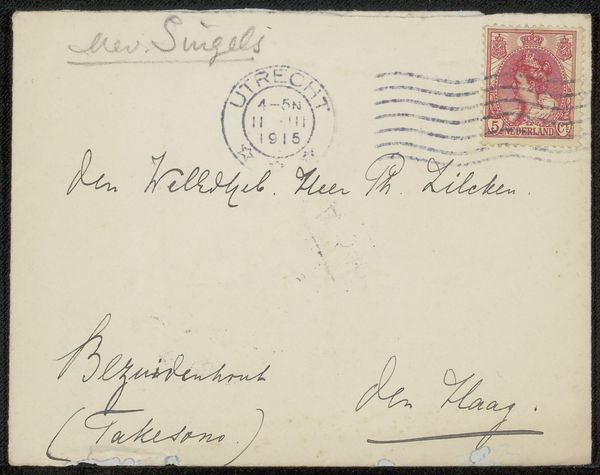

Editor: Here we have "Envelop aan Philip Zilcken," a pre-1903 ink and pen drawing on paper by Auguste Rodin, held at the Rijksmuseum. It's literally an addressed envelope, seemingly a candid glimpse into Rodin's correspondence. It strikes me as unusual for a museum to display such an everyday item. What catches your attention about it? Curator: What interests me most is the transformation of a mundane object, an envelope, into a piece worthy of display. How did the envelope become more than just a means of communication? Think about the recipient, Philip Zilcken; he was an artist, critic, and international figure in the art world. Rodin is, in a way, acknowledging and cementing his ties to Zilcken and the broader institutional network that supported him. This little drawing offers a view of the social life of art, doesn’t it? Editor: Yes, it does! It’s a tangible piece of evidence. So you see it less as a drawing and more as a document reflecting Rodin’s world? Curator: Precisely. Its value, arguably, is not solely aesthetic. What are the implications of placing this personal correspondence on display, rather than, say, one of Rodin's bronzes? Doesn’t it invite us to consider what is deemed worthy of preservation and public consumption? It raises questions about artistic reputation and the social networks in which artists operate. Editor: That makes me think about who decides what “art” is and how institutions play a big part in shaping our views. I’ll definitely look at art—and museums—a little differently now. Curator: Exactly. And hopefully, you will question what forces affect those decisions. The public display affects the significance attributed to the art itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.