![The Zen Eccentric Zhutou [right of a pair of Zhutou and Xianzi] by Yōgetsu](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2I2MmRiMDVmLWE4OGYtNDJlZi04MjVjLTJiYzZmNmU0ZmYzMC9iNjJkYjA1Zi1hODhmLTQyZWYtODI1Yy0yYmM2ZjZlNGZmMzBfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

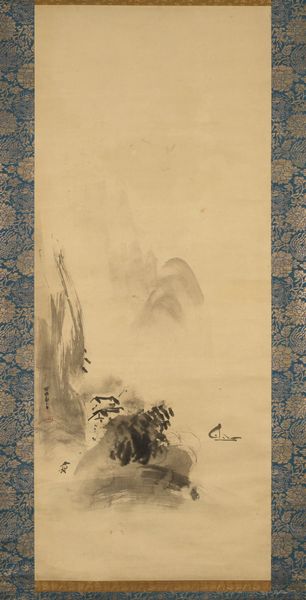

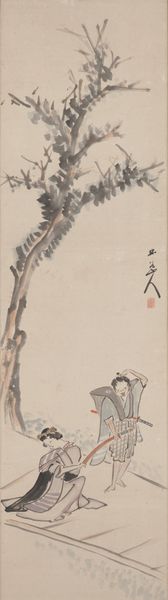

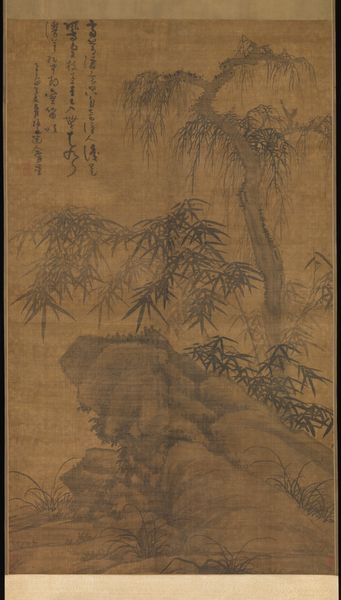

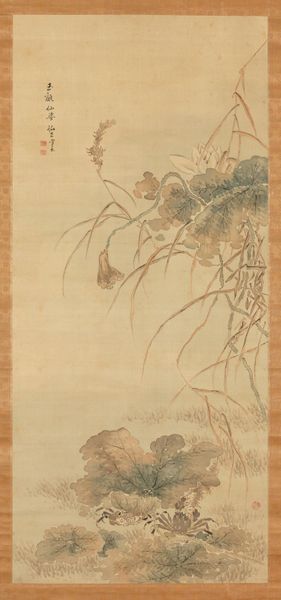

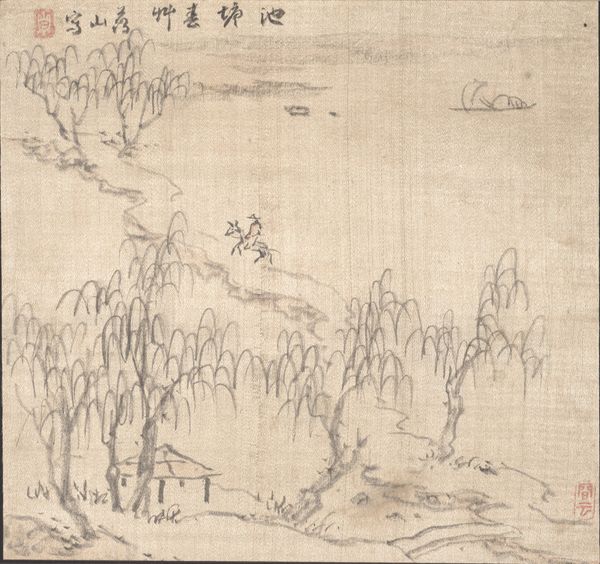

The Zen Eccentric Zhutou [right of a pair of Zhutou and Xianzi] late 15th-early 16th century

0:00

0:00

paper, ink-on-paper, ink

#

portrait

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

japan

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink-on-paper

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

yamato-e

Dimensions: 10 3/4 × 8 9/16 in. (27.31 × 21.75 cm) (image)47 3/4 × 14 3/8 in. (121.29 × 36.51 cm) (mount, without roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This ink-on-paper work, “The Zen Eccentric Zhutou,” attributed to Yōgetsu, dates from the late 15th to early 16th century. Part of a pair, with the other portraying Xianzi, it now resides here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: My first impression is quiet contemplation. A solitary figure, almost fading into the landscape. It’s like a visual haiku. Serene, yet…is that a dead fish he's carrying? Talk about juxtaposition. Curator: Indeed. "Zhutou," which literally translates to "Pig Head," was actually the name of a Chinese Zen monk. Depicting eccentrics was itself something of a trend, as it signaled a reverence toward the unconventional perspectives of outsider figures, and this appreciation had considerable resonance within Zen Buddhist thought at the time. This piece, alongside its pair Xianzi, can also speak to the rising importance of Chan Buddhism within Japanese art, and its impact on artistic identity during that time. Editor: That’s fascinating! Pig Head...not your typical Renaissance patron. It makes me wonder what Pig Head would think of our museums. Would he find irony in being framed and scrutinized centuries later? I can almost imagine him chuckling, maybe trading the fish for museum sushi. Curator: The tension between irreverence and profound spiritual searching are really at the heart of this composition. Consider the monochromatic palette—the deliberate sparseness of the brushstrokes which are, in effect, meant to draw the viewer’s attention to an idealization of poverty and austerity as crucial steps toward spiritual purification. Editor: So it’s less about precise rendering and more about evoking a feeling, a state of mind? That kind of restraint always speaks to me. It whispers instead of shouting. Still, it makes me want to know, was the real Zhutou this introspective or more of a Zen prankster? Curator: Likely a bit of both. Remember that embracing paradox was, and is, core to many Zen teachings. Even the act of producing art in this style involved a very rigorous method, but as a challenge to prevailing ideals about painting at the time. That tension created room to express ideas about freedom, nature, and transcendence, all within a structured setting. Editor: That makes perfect sense! This painting feels much less like a depiction and much more like a mirror for one’s own internal journey. You know, Pig Head’s got me thinking… maybe I should adopt a dead fish as my spirit guide! Curator: He might be quite effective. This painting, I think, is a call for a deeper understanding and acceptance of the unconventional among us. Editor: Agreed! It really inspires me to question the accepted narrative and maybe even embrace a little absurdity along the way.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

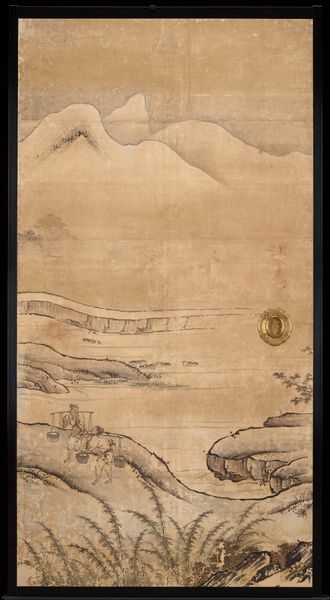

These paintings show two eccentric Chinese Zen priests, both of whom became famous for ignoring Zen restrictions on eating meat. Zhutou, at right, loved to eat boar meat and was known for carrying a boar head around town. His counterpart at left, Xianzi, was known to wander riverbanks eating clams, shrimp, and crayfish. Legend has it that Xianzi gained enlightenment while catching a shrimp, and this is the moment shown here. Despite their disregard for Zen monastic rules, such unruly priests were often held in high regard for following their own paths. This pair of hanging scrolls is among a small handful of works by the enigmatic painter Yōgetsu, known only by the seals impressed on his works. He is believed to have been a Zen priest living in Kyoto.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.