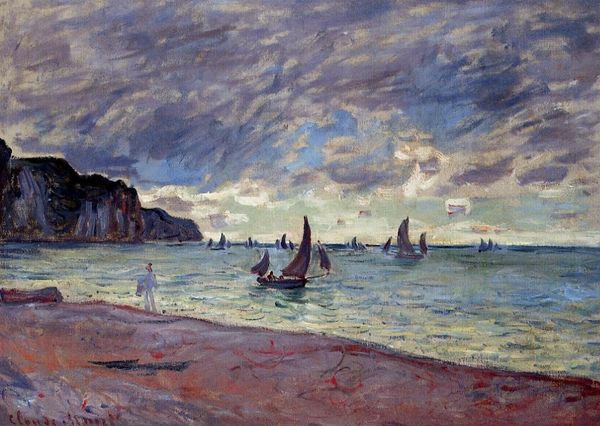

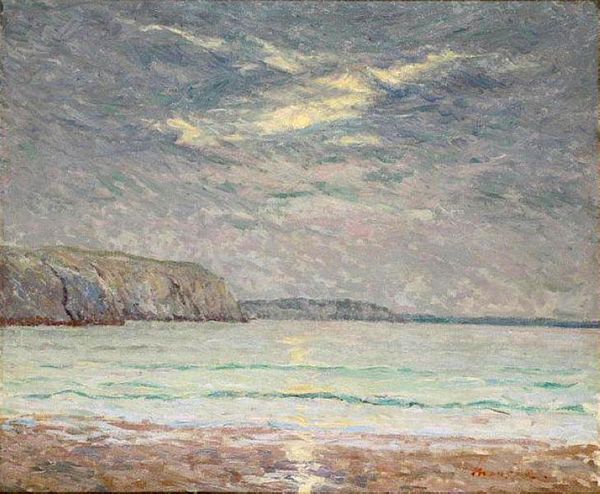

painting, plein-air, oil-paint

#

sky

#

cliff

#

painting

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

impressionist landscape

#

oil painting

#

ocean

#

rock

#

seascape

#

water

#

watercolor

#

sea

Dimensions: 109.5 x 87.5 cm

Copyright: Public domain

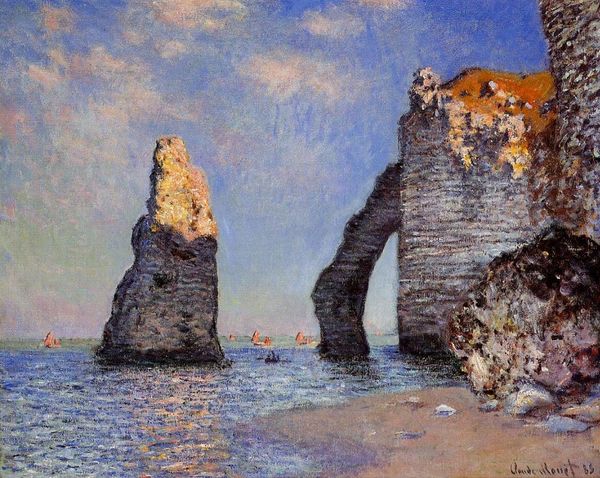

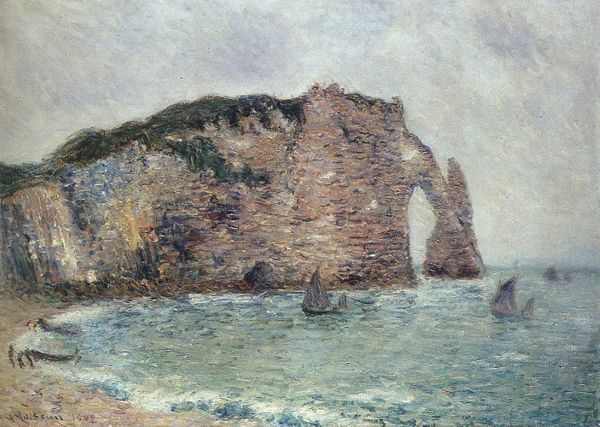

Curator: Ah, "The Cliffs at Etretat," painted in 1890 by Eugene Boudin. A striking example of plein-air painting from this period, wouldn't you agree? Editor: I do. Right off the bat, it strikes me as airy and full of wistful… longing, maybe? The soft blues and greys have that effect, like a faded memory. Curator: Boudin was, of course, a crucial figure in the Impressionist movement, influencing Monet. And cliffs are really interesting geographical formations—a visual symbol of power and resilience in the face of constant change, and perhaps cultural ideas around nature’s dominion. Editor: Absolutely. They're timeless. The little sailboats way off in the distance add a layer of humble scale too. Like tiny hopes sailing out into a big world. Or…tiny dreams destined to crash on the rocky shore? Curator: That’s the eternal question, isn’t it? Boudin's mastery is evident in capturing the transient nature of light on the water and the steadfast presence of those monumental cliffs. Note how he’s captured the effects of the breeze and changing light on the water through his rapid brushstrokes. The natural rock arch too becomes something more, an eye, looking out. Editor: Yeah, those quick, dabbed brushstrokes, feel almost photographic – like capturing a moment of sunlight filtering through a cloud before it vanishes. What strikes me is how, despite the scale, there's a sort of tenderness in the application, almost like he's cherishing this bit of coastline, immortalising it brushstroke by brushstroke. A memory for himself. Curator: Beautifully put. And considering that landscapes have always been imbued with cultural significance, Boudin could have well have been thinking about his attachment to the land as much as rendering visible phenomena. These sites of leisure were tied with national identity in 19th century France. Editor: I didn’t realize, so painting the beach as something timeless speaks about that moment in French cultural history as much as nature, huh? What a poignant record. This has really got me thinking about all that invisible context simmering beneath what just looked to me like, well, some rocks. Thanks. Curator: My pleasure. It’s in these layered dialogues between our gaze, what we’re shown and what symbols remain that artworks lives most vibrantly in our minds, I think.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.