painting, plein-air, oil-paint

#

sky

#

cliff

#

painting

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

impressionist landscape

#

oil painting

#

rock

#

seascape

#

natural-landscape

#

water

#

sea

Copyright: Public domain

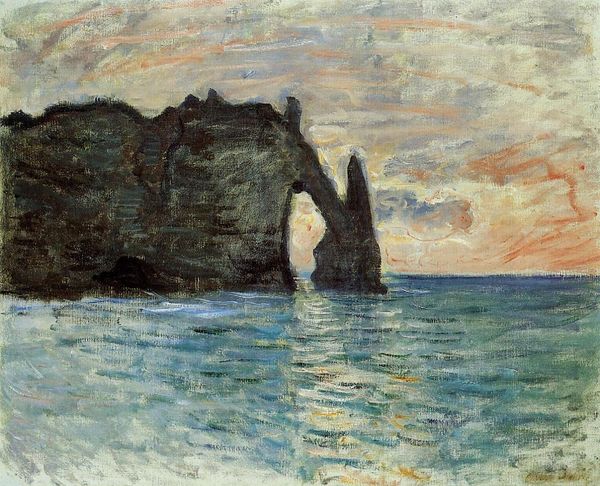

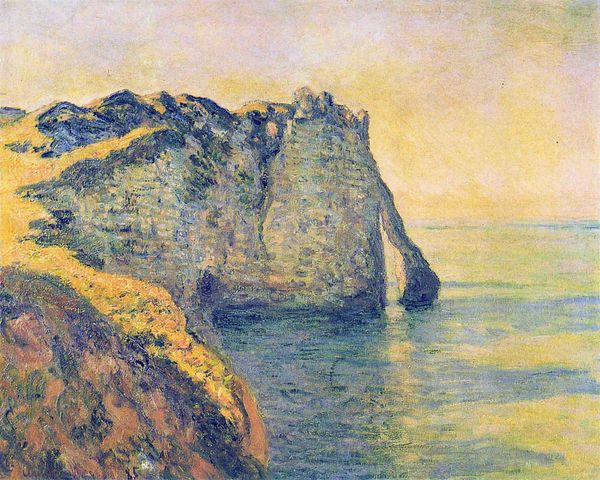

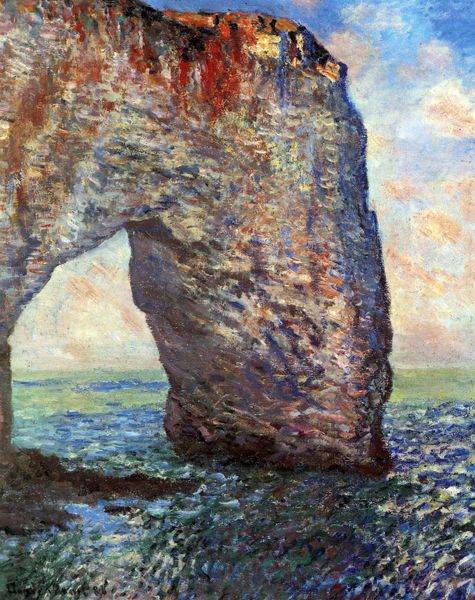

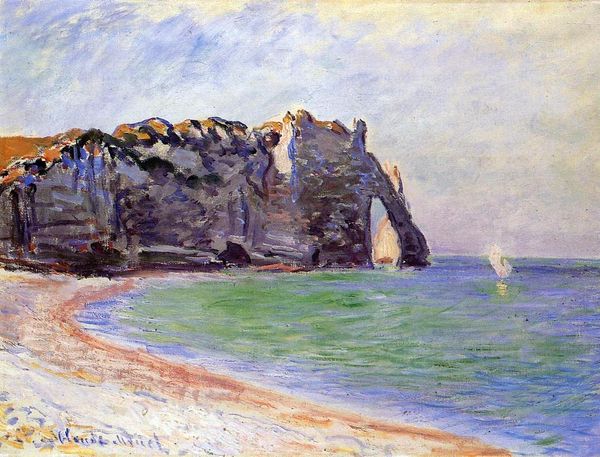

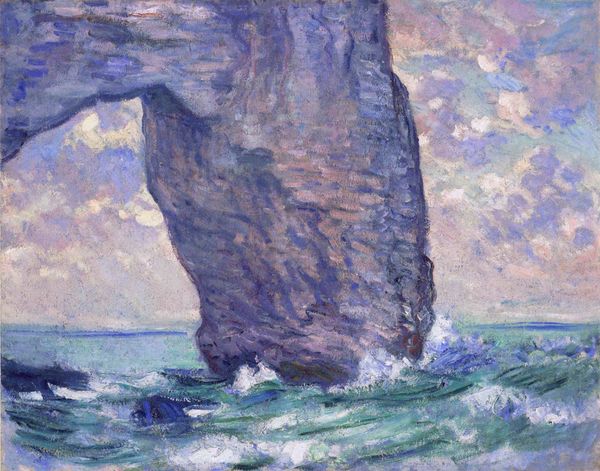

Editor: Here we have Claude Monet’s "The Rock Needle and the Porte d'Aval," painted in 1885 using oil on canvas. I’m struck by the texture of the cliffs, the almost crude application of paint. How should we approach this work? Curator: Let's focus on the materiality and the social context intertwined within this Impressionist landscape. Consider Monet's choice of *plein-air* painting. Why leave the studio? What possibilities for new labor division arose? Editor: Well, *plein-air* painting allowed for direct observation and capture of fleeting light conditions. It meant moving materials like easels, canvases, and paints – accessible materials for Monet – out of a controlled studio and into the changing coastal environment of Northern France. Curator: Precisely. And what did this relocation enable? The rise of leisure time amongst the bourgeoisie fuelled a demand for such landscapes, reflecting idealized visions of nature untouched by industrial labor, ironically. Do you think his painting methods helped that illusion? Editor: Maybe, yes! His broken brushstrokes seem to almost dissolve the rock formations, defying any solid structure... making them seem impermanent. Curator: Yet consider the pigments themselves - ground minerals, commercially produced. And think of the merchant who sold him these supplies. There is hidden labour in every stroke! Editor: So you’re suggesting Monet, even when seemingly focused on capturing the ephemeral, was deeply involved with, and reliant on, a wider system of material production and consumption? Curator: Exactly. This is not just about "light." It's about a social network, revealing the hidden labor sustaining the aesthetic experience of landscape painting at that time. Editor: That's a really interesting perspective – thinking about the art materials as embodiments of labor, and that as materials move locations, and contexts shifts our interpretation of artwork changes. I see it now! Curator: Indeed! By tracing these connections, we see that art is never created in a vacuum; it's embedded in complex economic and social structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.