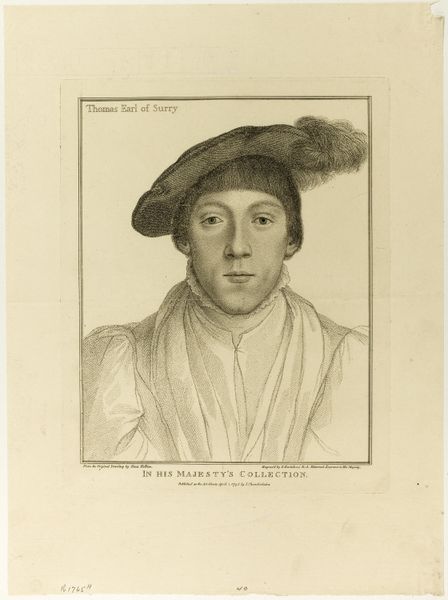

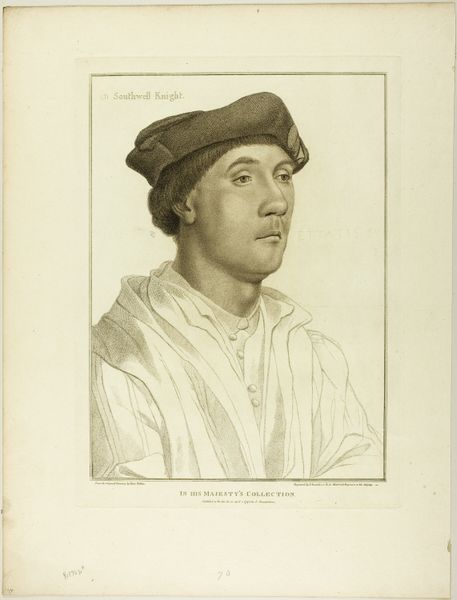

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

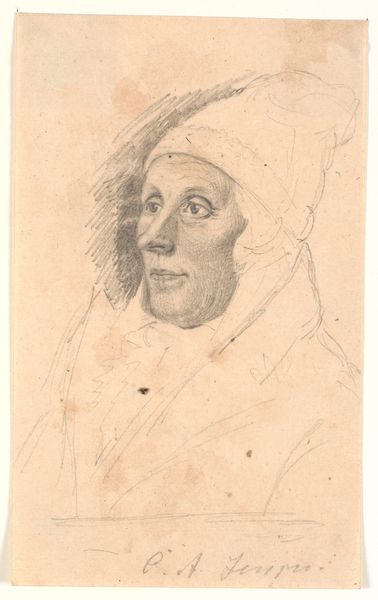

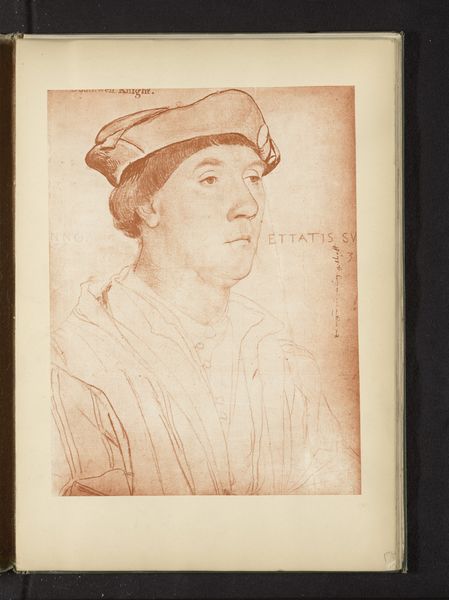

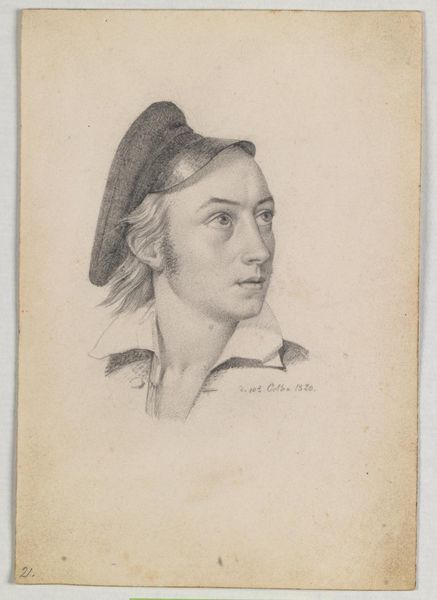

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

paper

#

portrait drawing

#

italy

#

engraving

Dimensions: 378 × 296 mm (image); 431 × 329 mm (plate); 461 × 348 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Francesco Bartolozzi created "Lady Rich" around 1795. It's a portrait print, using engraving on paper, currently residing here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: The fine lines give it such a delicate, almost ephemeral quality. It’s as if we’re peering into a memory. The light catches on the folds of her elaborate headwear… it's really quite stunning, although the expression strikes me as more reserved than 'Rich' if I may be so bold. Curator: Perhaps. Consider though, the historical context. This work exists in a time defined by rigid social structures where public displays of emotion, particularly for women, were carefully controlled. Class defined and constrained everything. Editor: And her garments absolutely declare her high status! Notice the details of the hat. That's no commoner’s attire. In portraiture, clothing often symbolizes more than just fashion; it speaks volumes about the subject's identity and position. I am really drawn into its lines: I feel almost suspended in time! Curator: Absolutely. And looking closer at Bartolozzi’s process allows us to challenge the assumption that “Lady Rich” is merely a portrait of a woman. By the late 1790s, printed portraits circulated widely, which in effect performed and reified one’s social standing through a visual representation. This portrait, then, has implications regarding female aristocratic identity, power, and performance in eighteenth-century Britain. It also opens up into an important set of questions around wealth and gender in this period. Editor: A powerful image. Curator: Indeed. "Lady Rich" offers a lens through which to explore the complexities of class, gender, and visual representation in the Neoclassical era. Editor: It really shows how even seemingly straightforward portraits can offer profound insight. The key is in observing symbols and reflecting on meanings through history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.