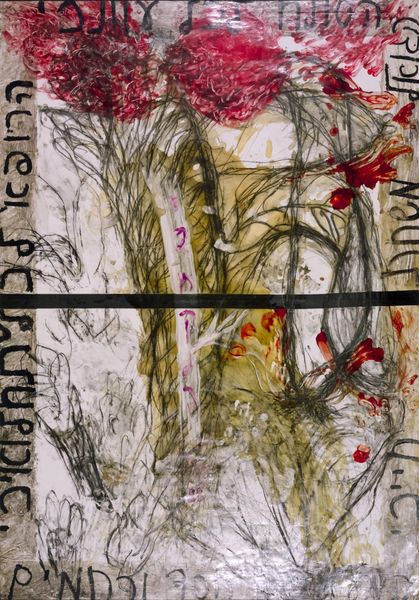

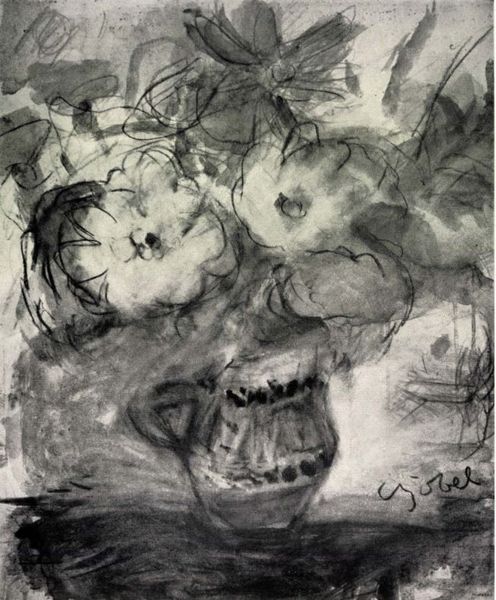

Dimensions: support: 2001 x 1402 mm

Copyright: © Moshe Gershuni | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

Curator: Before us hangs Moshe Gershuni’s "18 Cyclamens," housed here at the Tate. Editor: My immediate impression is raw emotion. It feels almost violently expressive with those splashes of red against the muted background. Curator: Indeed. The cyclamen flower, often a symbol of sincerity and love, appears here… transformed, almost wounded. Look at the Hebrew script intermingling with the floral depiction; it evokes layers of meaning, perhaps loss or remembrance. Editor: I wonder about the institutional framing of such personal work. How does placing it in a gallery affect its power? Does it become a historical artifact of a private grief, or a public expression of shared pain? Curator: Perhaps both. Gershuni was deeply affected by the political and social landscape of Israel, and the imagery hints at the fragility of beauty in times of conflict. The cyclamen becomes a potent symbol. Editor: It certainly disrupts any easy sentimentality. It reminds us that even beauty can be a site of struggle. Curator: A powerful piece to contemplate. Editor: I agree. It leaves you pondering the weight of visual language.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 9 months ago

⋮

Both works are from a series of eighteen known as the Cyclamen Series, and were executed in Israel in 1984. The fact that there were eighteen is of significance for the number eighteen has a symbolic value in Kabbalah. Eighteen in Hebrew is Chai which means world or life. When people make donations to synagogues they do so in multiples of eighteen. Thus a series of eighteen works would have very specific connotations for an Israeli citizen. Moshe Gershuni was born in Tel Aviv into a family of first generation Polish immigrants. From early beginnings as a conceptual artist Gershuni, for the last twenty years, has been painting in an expressive manner. His work is autobiographical as well as touching on matters of national and universal value. The principal motif of this group of paintings is the cyclamen which, since the War of Independence in 1948, has become Israel's national symbol of regeneration. A popular song about the battle on the road to Jerusalem contains the line 'One day spring will come and cyclamen and anemones will flourish in the valleys'. In Chaim Guri's lyrics cyclamen grow on the spot where soldiers have fallen in battle; the soldiers were transformed into flowers. Painted after the invasion of Lebanon by the Israeli army in what is considered by some Israelis as the first 'unnecessary' war, Gershuni's series thus concerns reconciliation. Militarism is replaced by natural growth and military order by natural order. The inscriptions around the side of the paintings, written in Biblical Hebrew, are quotations from the the Psalm of David and are expressions of forgiveness and reconciliation: 'Who forgives all your iniquities, who healeth your diseases, who delivers your life from destruction and who crowneth you with loving kindness and terrible mercies.' (Psalm 103:3-4, The Holy Bible: New King James Version.) Earlier works by Gershuni depicted soldiers but here the cyclamen has replaced the soldier and becomes a complex symbol of growth, mourning, sexuality, femininity and life in a context of death, machismo and blood. The cyclamen becomes at once plant and sexual organ, wound and flower. Its position is at times erect, at others limp. It may be dried up and shriveled or in full bloom. Male and female are constantly confused in these expressions of sexual ambiguity. Gershuni underwent a personal crisis in the early 1980s when his marriage broke down and he declared himself to be homosexual. The cyclamen becomes a symbol of homosexual love which, given that it also symbolises a soldier from the Israeli army, transforms the painting into a subject of taboo. Homosexuality is not admitted in the Israeli army. These paintings are personal reflections and memories; memories of his childhood - he was twelve at the time of the War of Independence - of the time he spent as a farmer before he became an artist and reflections on his relationship with his lover Isaac whose name appears in the paintings. But Isaac is more than the name of his lover. Isaac was the son of Abraham who was prepared to sacrifice him to God. Isaac becomes, therefore, a symbol of castration of the son by the father. But he is also a symbol of national sacrifice, of young boys going to war. Gershuni painted these works on the floor of his Tel Aviv studio on all fours using liquid paints, laquers and paint sticks which are at once paint and representative of body fluids. The materials are applied by pouring and staining, smearing with rags and hands but no brushes. Itamar Levi has written: 'The technique doesn't simulate a beast devouring its prey or a baby playing innocently with its faeces, but the position of the wounded, enraged animal or a man whose soul is embattled by lust and guilt. When the viewer steps back and sees the borders of the paper, the division of the space and its ground plan, the images, the symbols and inscriptions, he experiences the act of man's rise from all fours to an erect stance.'('With the Fat of my Blood' in Moshe Gershuni 1980-1986, exhibition catalogue, Israel Museum, Jerusalem 1986 unpaginated). It is the transition from the pre-cultural to the cultural. Martin Weyl, former Director of the Israel Museum, has written: 'In Gershuni's works there is a synthesis of crudeness and sophistication, instinct and intellect, tragedy and irony. They unite the aesthetics of the gutter with the pathos of the sublime, the repugnant with the wonderful.' (Moshe Gershuni 1980 - 1986 op.cit.). Gershuni's work is a bold synthesis of the public and private, executed in a country whose anguished debates are reflected in the ambivalent and restless nature of these paintings. Further reading:Moshe Gershuni 1980 - 1986, exhibition catalogue, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem 1986 Jeremy Lewison and Giorgia BottinelliFebruary 2002