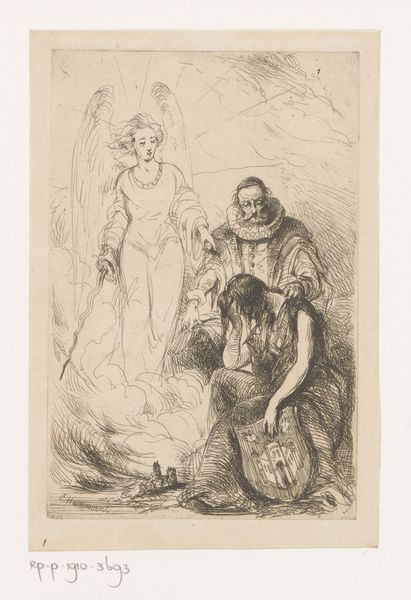

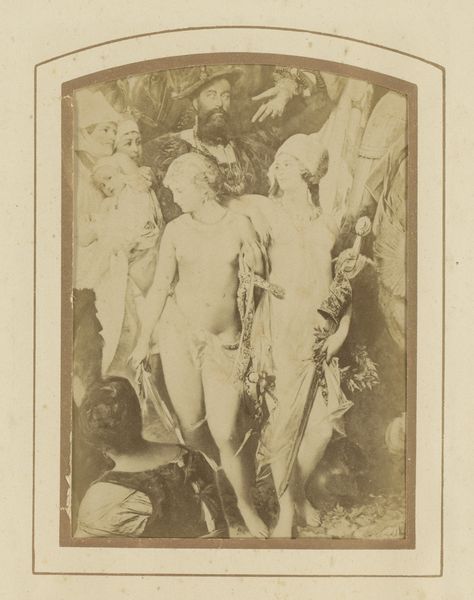

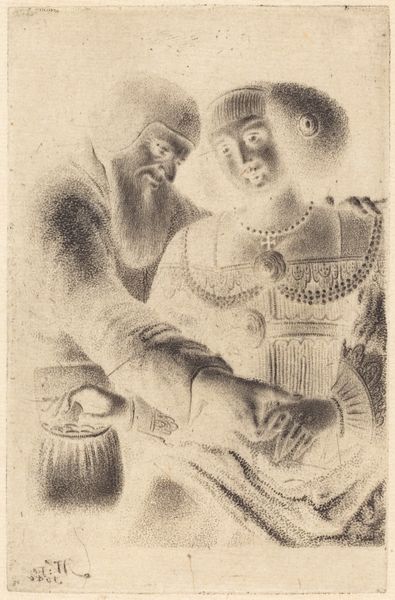

Dimensions: height 355 mm, width 275 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Julien-Léopold Boilly's "Portret van de advocaat Pierre-Édouard Lémontey" from 1822, an etching on paper. It’s incredibly detailed. What strikes me is its strangeness; it's this mix of meticulous craft and almost dreamlike imagery. What can you tell us about this piece? Curator: From a materialist perspective, I'm drawn to consider the means of its production. Boilly, primarily a painter, utilizes the etching process, a relatively accessible printmaking technique. How does the labor involved in creating this print – the repetitive action of etching lines, the materials used like the copper plate and acid – democratize art production and reception, challenging traditional distinctions between painting and printmaking? Editor: That's a fascinating point. So, it's not just about the image itself, but also about the social implications of its creation? Curator: Precisely. The act of etching allows for multiplication and wider distribution. How does that influence Lémontey's social standing and accessibility as a figure, transforming from a painted portrait for the elite to a printed image potentially circulated more broadly? This also begs the question, what type of paper and ink were used, and how do those choices reflect on access and artistic value at the time? Editor: Interesting. I hadn't considered the implications of using printmaking as a medium for portraiture then, compared to the higher status of painting at the time. Curator: Think about it in terms of the rise of the bourgeoisie. Etching provided a relatively inexpensive method for representing and consuming imagery and information. Boilly's choice might be indicative of the shifting landscape of art patronage and consumption, which were, in turn, affecting the portrayal of people. It moves us away from merely discussing symbolism and focuses our attention on material contexts and the social position of art itself. Editor: This really changes my view of the work. It is not simply a portrait of one person. Thanks, it definitely changes my thinking about the means of producing images back then.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.