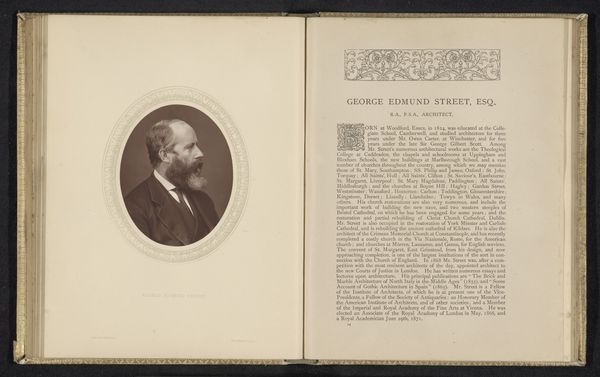

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

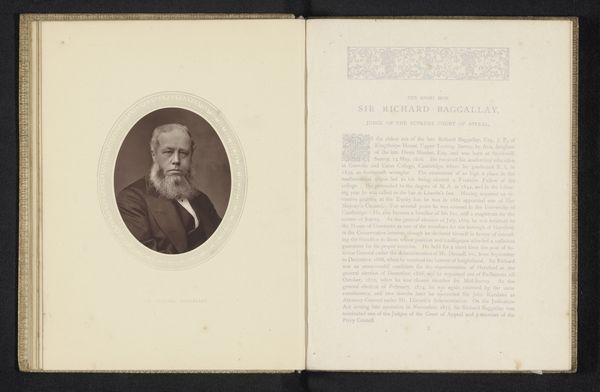

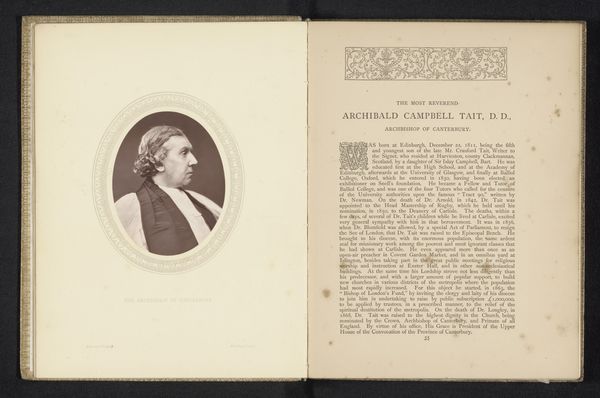

portrait

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 115 mm, width 89 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

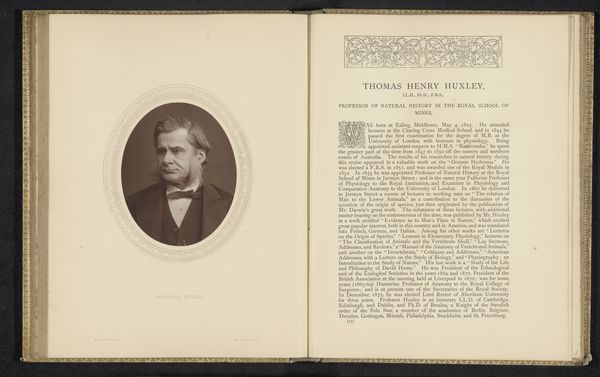

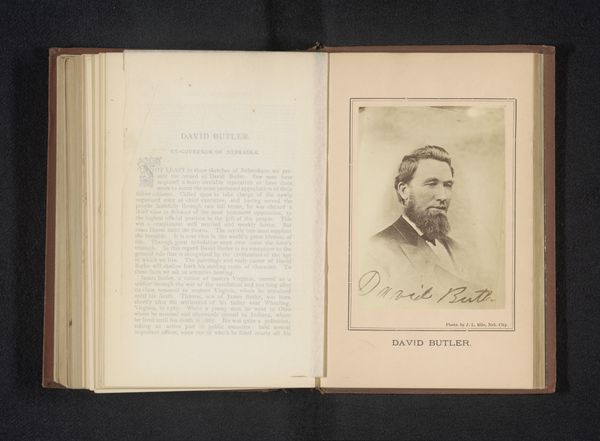

Curator: This open book displays a photographic portrait of Rev. C.H. Spurgeon, before 1880, produced by Lock & Whitfield, likely a gelatin silver print. There’s something inherently solemn about these early photographic processes. What is your initial impression? Editor: There's a wonderful stillness here. I imagine the long exposure required immense patience from Spurgeon; he embodies gravity and composure in this subdued palette, almost a monochrome echo of a person. Curator: These portraits, reproduced as prints, democratized image circulation. We see an engagement with technology making representations of prominent individuals accessible to a wide public audience, moving beyond the elite patronage of painted portraits. Editor: Precisely! And that accessibility shifts the work’s meaning. It’s no longer solely about Spurgeon, but about his image entering everyday life, becoming a symbol of faith and Victorian ideals circulated through mass culture. Did this influence or challenge perceptions of religious authority? Curator: It’s a critical point. The very act of mass reproduction raises questions. The gelatin silver printing process – an advance on earlier, more cumbersome methods – shows how new technologies affected visual communication and social representation. Was his persona enhanced, or diluted? Did mechanical reproduction affect ideas of authenticity? Editor: I love this perspective. Seeing his face, infinitely replicated, invites both reverence and detachment. Did Spurgeon collaborate on how his image would circulate? Or was he, in some ways, a subject of photographic industry as much as its benefactor? Curator: Lock and Whitfield were important portraitists of their day, producing images for publications intended for a growing middle-class readership. Studying the photographic processes informs our understanding of art as industry, labor, and mass consumption. Editor: Absolutely. It’s also haunting, thinking about how we experience images of the past now, compared to those for whom these prints were entirely contemporary. Curator: Indeed, by tracing material transformations, we see the evolution of social and cultural value. The photographic industry shapes modern image-making, just as Spurgeon shapes spiritual dialogue for generations to come. Editor: It really highlights how time can transform not only materials, but also our perception of their significance, revealing a story both concrete and profoundly ephemeral.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.