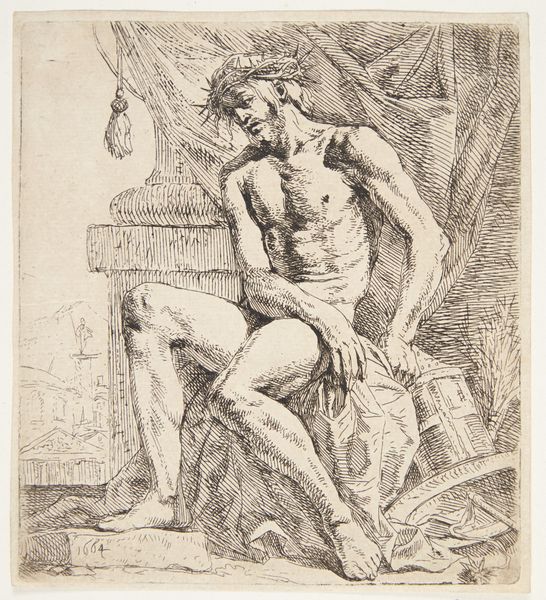

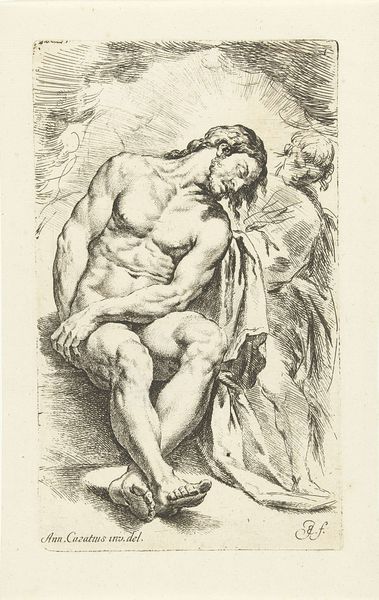

print, etching

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 14 5/16 × 9 1/16 in. (36.35 × 23.02 cm) (sheet)8 13/16 × 5 5/16 in. (22.38 × 13.49 cm) (plate)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Jan de Bisschop's etching, "Dead Christ," from 1671. The stark black and white creates such a somber feeling. I’m struck by the artist’s attention to detail, especially considering this is a print. What can you tell me about it? Curator: Bisschop's choice of etching as a medium speaks volumes about the democratization of art production during the Baroque period. Think about the process itself: the artist manipulating the metal plate, using acid to bite away at the surface. This laborious process creates a matrix for reproduction, allowing this powerful image of the dead Christ to reach a wider audience than a unique painting ever could. How does knowing this process influences your understanding? Editor: It does make me think about the distribution of images. It moves beyond the singular masterpiece intended for the wealthy and towards a wider public. How might the consumption of images such as these impacted devotional practices? Curator: Exactly! Etchings were much more affordable. Consider, then, the economics of faith: How does the increased availability of religious imagery reshape the power dynamics between the church and the individual believer? And beyond devotional impact, could the relatively wider circulation and reproducibility of these prints perhaps function as a form of cultural propaganda? Editor: That’s a really interesting angle. I hadn’t considered the work beyond the purely aesthetic. Curator: It's about labor, materials, and access. That transforms this from a simple religious scene into something much more complex – a reflection of its social and economic context. Thinking about it now, the relative ease in reproducing the image compared to producing a monumental painting emphasizes Christ's democratic embrace of the lowest of society in spirit. Editor: This has definitely given me a lot to think about in terms of how art functions within a society. It's not just about aesthetics. Curator: Precisely. By focusing on the means of production and distribution, we gain insight into the forces that shape both the artwork and the culture that consumes it.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

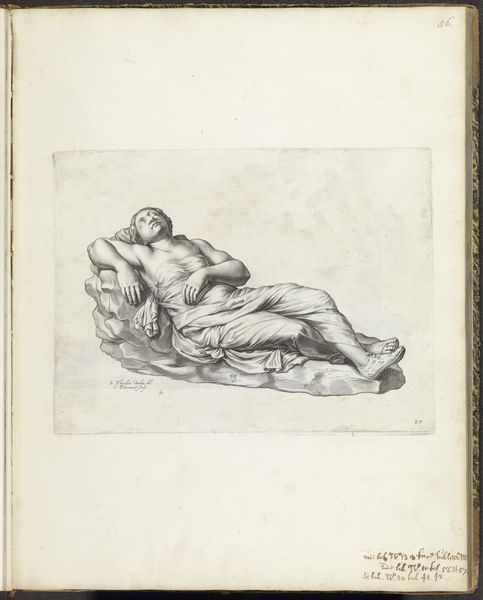

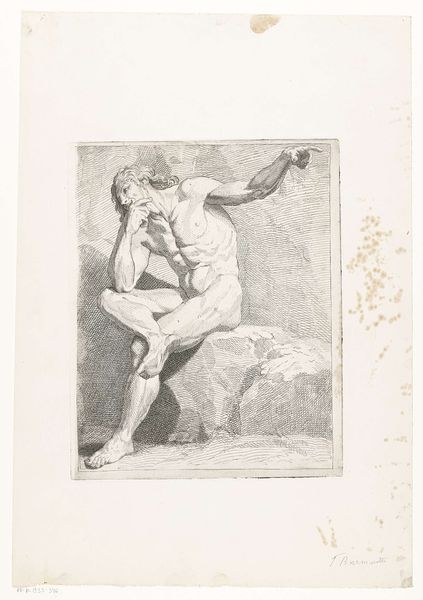

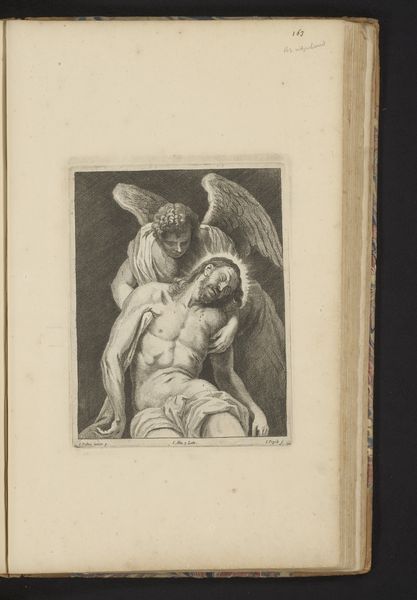

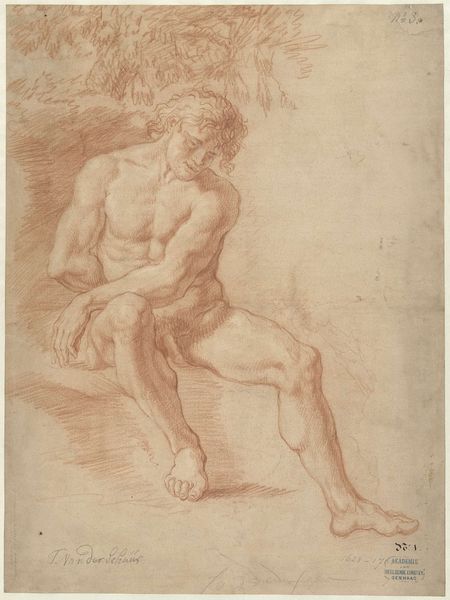

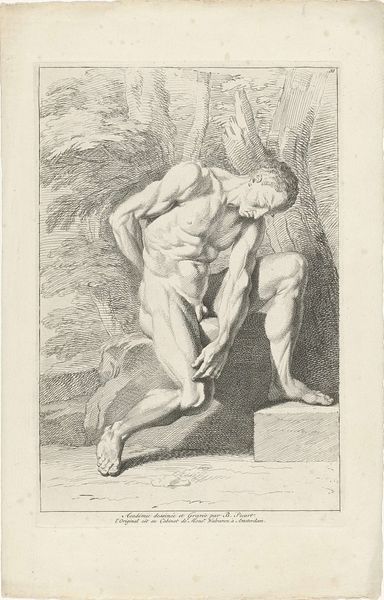

This etching of the dead Christ supported by an angel was executed by the Dutch lawyer and amateur artist Jan de Bisschop after a drawing attributed to the great Bolognese painter Annibale Carracci, which is now in the Albertina, Vienna. The print was part of an influential drawing manual de Bisschop produced The Paradigmata Graphices Variorum Artificum, which feature etchings of the human body after Italian Renaissance and Baroque works. Published in the Netherlands in 1671, this influential drawing manual introduced aspiring northern artists to the canon of Western art, which was predominantly Italian and thus—except to the lucky few who could travel to Italy—known largely through prints and copies. De Bisschop probably never went to Italy, so he collaborated with draftsmen who had traveled there as well as studied prints and drawings of Italian art. Drawing manuals like these were common teaching tools for artists and amateurs alike, for drawing instruction began with learning to copy prints and drawings.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.