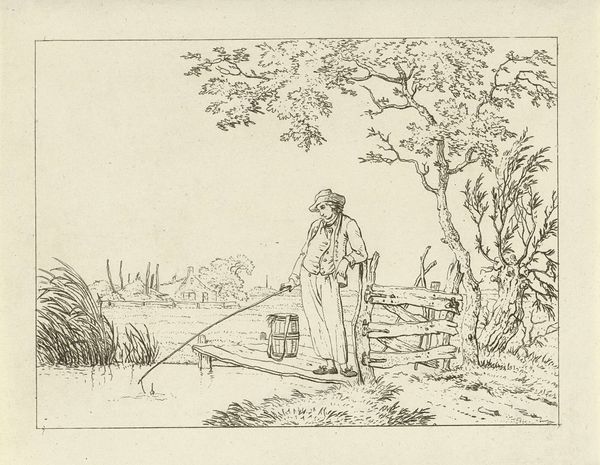

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, "Visser op vlonder," or "Fisherman on a Platform," created between 1781 and 1822 by Hermanus Fock, immediately strikes me with its understated elegance. What are your first thoughts? Editor: My immediate impression is of quiet solitude. The textures of the engraving suggest a dampness, the way the reeds bend, the rough-hewn timbers. It feels like the stillness just before a storm. Curator: The print is rooted in a romantic vision, I think, in its celebration of simple rural life, but considering Fock's era, do you read other socioeconomic influences into the work? Editor: Definitely. Look at the fisherman's clothing. It's worn, but carefully maintained. There's a relationship suggested between labor and a deliberate presentation of self. The labor is slow but considered: the choice of materials to construct the fishing platform is not accidental. It reflects the reality of working the land and the resources accessible to the fisherman. Curator: I see the fisherman as existing within broader networks. His clothing, his activity - they signal not just an individual, but an affiliation. How does that idea of a "working identity" inform your perspective on art of this period? Editor: I'm most interested in the materiality of that "identity." Fock employed engraving, a painstaking, craft-based medium to capture this scene. Engraving requires skill, labor, and time. This act elevates everyday life, especially labor and nature. It turns the common into something carefully considered, something to be revered. Curator: Yes, it's not just the fisherman, but the entire ecosystem, rendered with a sort of contemplative intimacy that romanticizes an existence likely rife with economic struggle. It highlights the social and cultural dimensions in romanticizing "folk art." Editor: Agreed. The print itself becomes a commodity, one that circulates and mediates that romanticism. It is not a documentary. So while the content can appear romanticized or idealized, it reminds me that the construction of landscape or occupation in the form of a print participates directly in contemporary economy and ideology. Curator: Understanding the intersections of these visual representations with the era's political and economic structures really opens new layers in an ostensibly simple scene. Editor: Exactly. Thinking through those lenses transforms a quaint image into a complex statement about work, material, identity, and our place in history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.