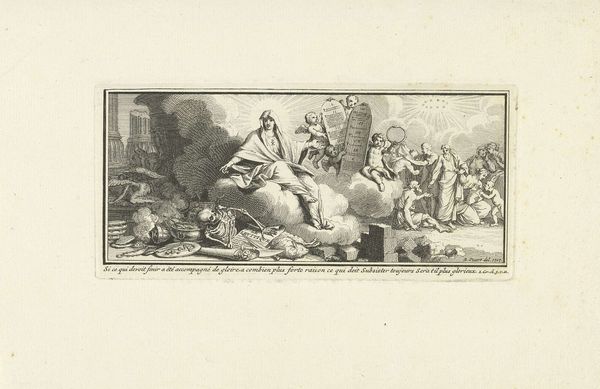

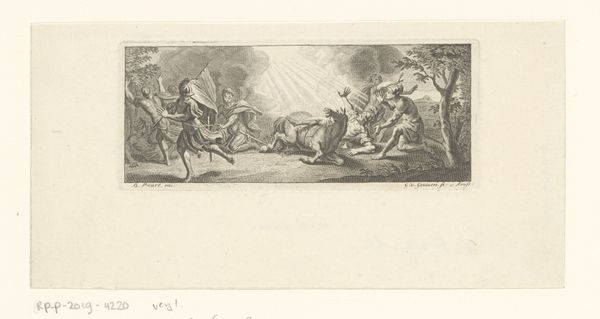

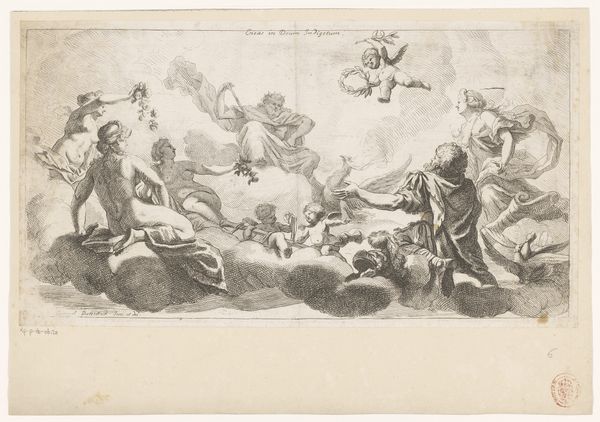

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 48 mm, width 91 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. The artwork before us is titled "Apollo met musicerende en schilderende putti," or "Apollo with music-making and painting putti," crafted in 1752 by Jacques Philippe Le Bas. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial impression is playful but rather formal. The crisp lines and classical elements juxtaposed with the frolicking putti—it feels both grand and intimate, somehow. Curator: Indeed. As an engraving, Le Bas's expertise lies in the manipulation of line and form to create this scene. We can see a clear commitment to the traditions of the Baroque, but notice the clean, sharp lines that denote form and space using solely the printed mark. What raw materials and processes would need to be understood by a printing maker to construct a product like this in 1752? Editor: Considering the period, I can’t help but read the image allegorically, especially in terms of power and class. The putti, representing different artistic disciplines, almost serve as symbolic ornamentation surrounding Apollo. The entire composition speaks to art as a tool to reinforce social order and elitist ideas about high culture. Curator: I see your point about power dynamics and consider what forms of labour practices underpin those readings of the artwork. Look closer—at how the artist utilizes different densities of engraved marks to describe shadows and highlights, thus generating an entire spectrum of value with a very limited amount of material and ink on the plate. It highlights a significant amount of embodied expertise of the plate worker, Le Bas in this instance. Editor: Agreed, and how that labour becomes a component of meaning. It reminds me that even seemingly innocent depictions were, and are, never apolitical; artistic endeavors in 18th-century Europe were heavily influenced by patronage, and such imagery justified it, I argue. We also ought to acknowledge that the materials, even the copper or inks employed, all exist within vast webs of colonial trade at this point in history. Curator: Precisely! A full investigation of how such prints as this move around the world via complex commercial networks reveals something fundamental to our comprehension of early consumer cultures. The production of such things relies on, facilitates, and advances forms of globalization. Editor: Absolutely, which compels us to ask questions about accessibility, cultural capital, and, inevitably, power. Examining it in such light changes my earlier feelings, to be honest. Curator: I agree. Investigating an artwork by discussing processes and materials allows us a glimpse into larger production processes. What seems initially playful quickly becomes enmeshed with complicated themes about networks and economics of materials and labour, as you say! Editor: And from a social perspective, it demonstrates the historical threads woven through our cultural objects.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.