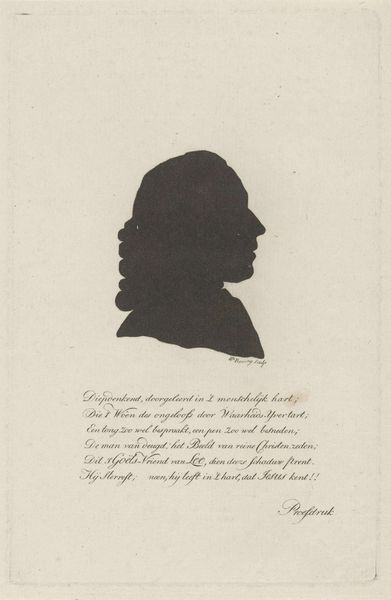

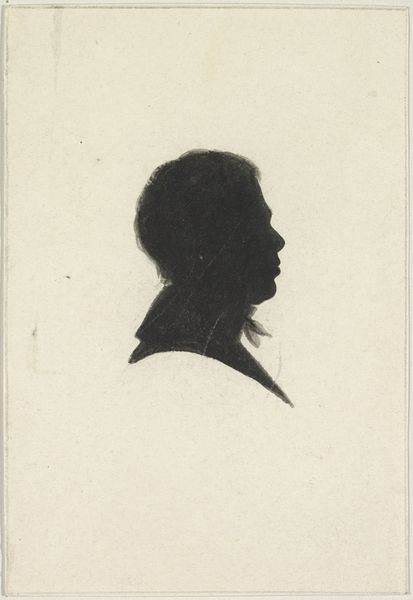

drawing

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

15_18th-century

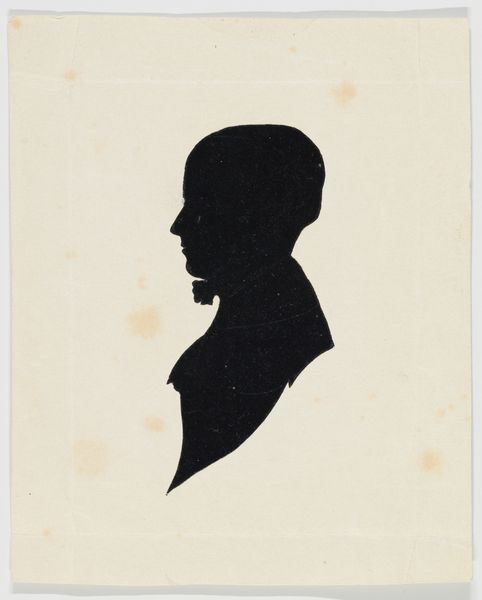

Dimensions: height 116 mm, width 74 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a drawing entitled "Silhouet van Adriaan Gillis Camper, naar rechts kijkend," dating from sometime between 1765 and 1834. It's attributed to Wessel Lubbers and held at the Rijksmuseum. It's a stark black silhouette on a pale background. The lack of detail is interesting. How would you interpret this work? Curator: What jumps out is the historical context of silhouette portraits. In the 18th and 19th centuries, before photography became widely accessible, silhouettes were a popular, and cheaper, form of portraiture. They democratized image making, making portraits accessible to a broader public than painted portraits. Editor: That's fascinating. It seems so…minimal now. Curator: Exactly. The reduction of a person to a mere outline raises interesting questions about representation. What aspects of identity are emphasized, and what is lost? How did this simple form serve the social function of commemorating or representing individuals within their communities? Consider also how its relative inexpensiveness may have provided opportunities for groups historically excluded from formal portraiture to have their likeness preserved. Editor: So, even something that seems visually simple could be tied to big social and political shifts? Curator: Absolutely. The proliferation of these silhouettes reflects a shift in who had the right to be seen, or at least, to have their likeness recorded. These were often collected in albums and circulated among families and social circles. Editor: I guess I had underestimated it. It seems that portraits can be important and have an important public role no matter what they look like. Curator: Precisely. Looking closely at seemingly simple things can reveal complex histories of representation and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.