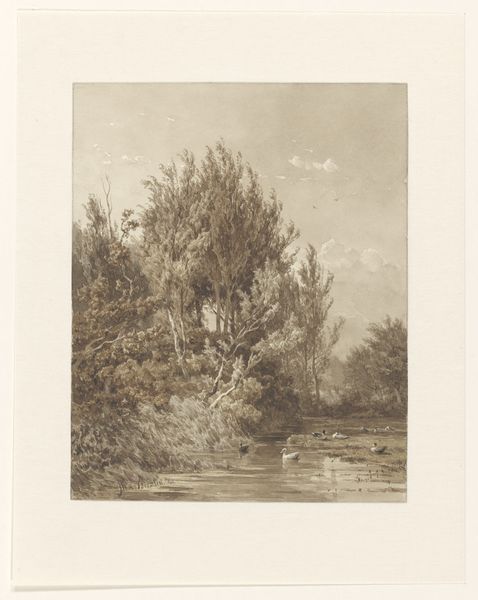

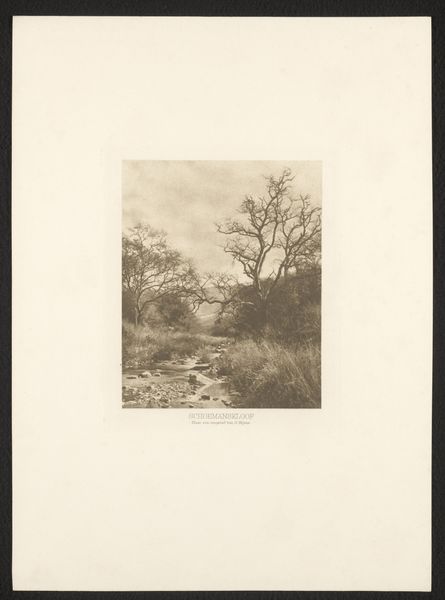

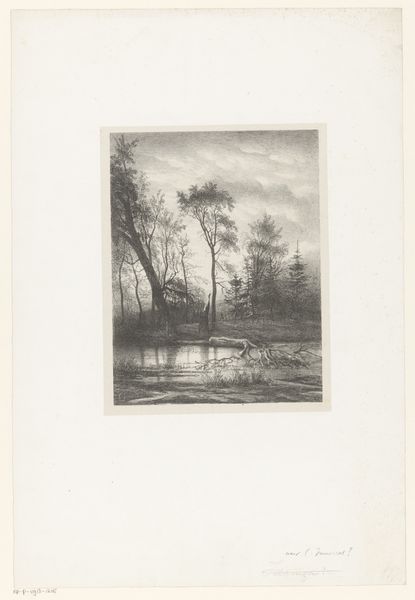

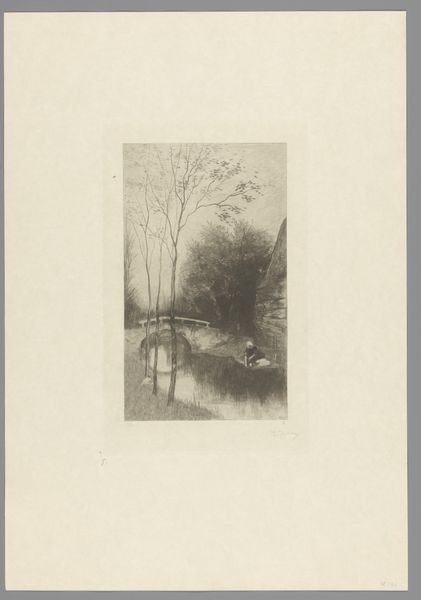

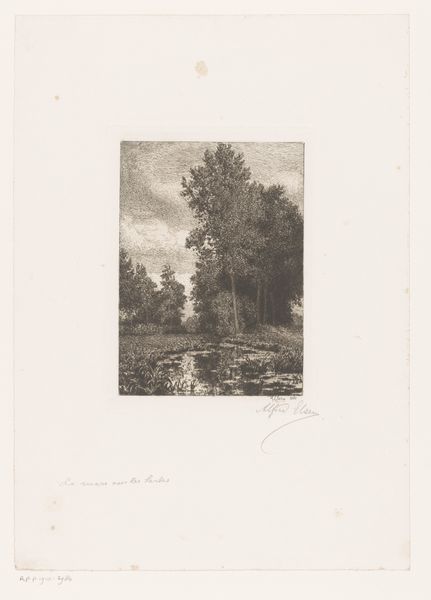

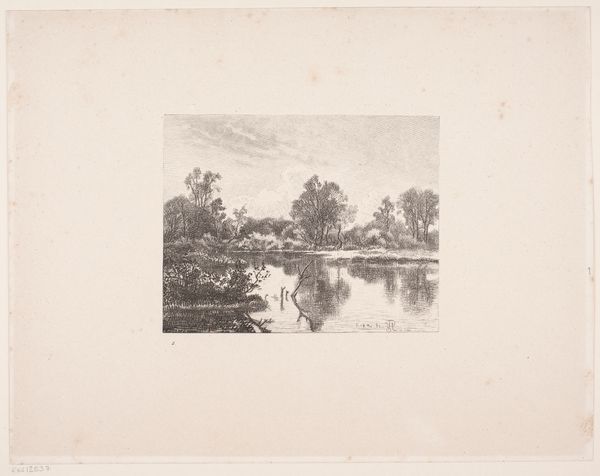

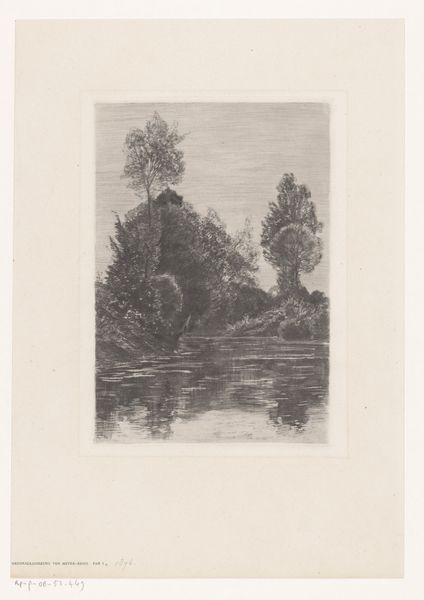

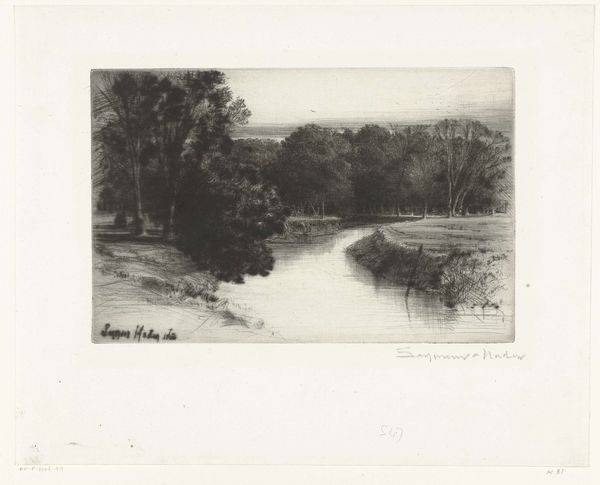

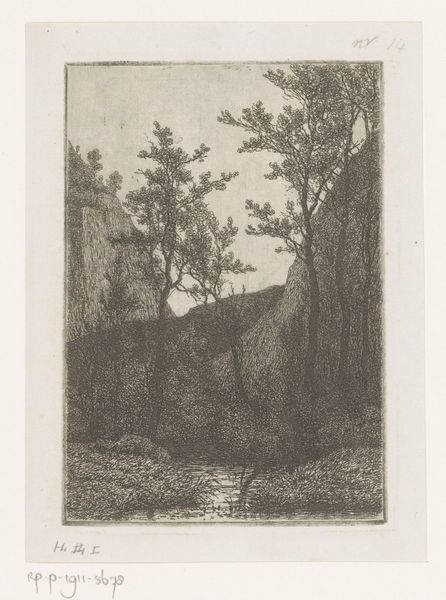

aquatint, print, etching

#

aquatint

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

romanticism

Dimensions: 6 9/16 x 4 11/16 in. (16.67 x 11.91 cm) (plate)14 x 18 in. (35.56 x 45.72 cm) (mat, Size I)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Immediately, this etching evokes a serene calmness, a kind of hushed reverence for nature. Editor: Let’s delve into this further. We're looking at "Morning," a piece created by James D. Smillie in the 19th century, currently residing at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It's an aquatint and etching, predominantly showing a landscape. Curator: Yes, and you can really see the skill with which Smillie manipulated the copper plate, balancing areas of dense hatching with the smooth, tonal areas created through the aquatint process. It strikes me that his choices speak directly to the commodification of landscape. Etchings, as multiples, allowed wider audiences to experience these idealized scenes. Editor: Indeed. The art market's burgeoning middle class lapped up scenes such as these, packaged for domestic display. The picturesque, readily reproducible. The very concept of “Morning”, promising the renewal of the day and therefore continued production, feels intentional. But let's consider the landscape itself; the composition pulls the eye through a sequence of horizontals. Is it Romanticism? It feels... restrained. Curator: I would call it a studied, manufactured version of Romanticism. Smillie wasn't tramping through the wilderness—he was engaging with a specific representational tradition, one steeped in colonial projects and the appropriation of nature's resources for commercial ends. Note how nature is tamed, brought into neat reflections in the still water. Editor: Good point! This relates directly to the role of institutions, doesn’t it? Galleries shaped both artists’ careers and public taste, standardising expectations of ‘art.’ The lack of true wilderness feels purposeful, almost reflecting a bourgeois sanitization of the more dangerous side of untamed lands. It also reflects a longing for a simpler time when in the late 19th Century so many things were moving so fast! Curator: And there's that inherent contradiction, the simulacrum of nature produced by industrial means! Editor: Well, regardless, its beauty persists. And, I guess, in thinking about it more, maybe it's still relevant because even now in our world oversaturated by screens, there's a great appeal of returning to a tranquil state, a meditative, uncomplicated experience, that this little etching still offers. Curator: Perhaps Smillie's hand reminds us that art is inherently an artificial construct. Appreciating this tension is perhaps where its enduring allure lies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.