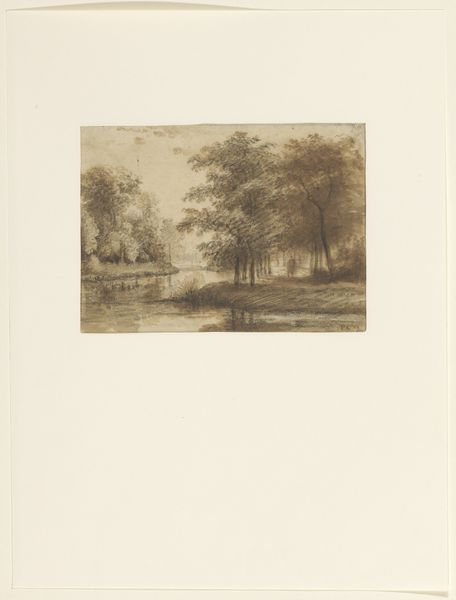

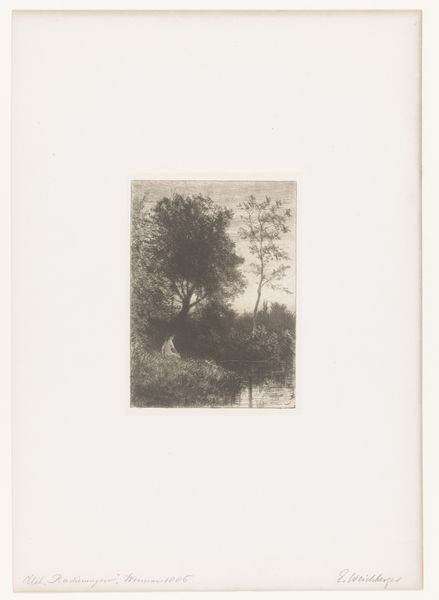

Dimensions: height 293 mm, width 235 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I'm drawn to the quiet serenity of this piece. It's a pencil drawing titled "Landscape with Water and Ducks," created by Jan Willem van Borselen around 1861. Editor: Yes, there’s definitely a tranquil stillness. The subdued palette creates a certain hushed atmosphere, a kind of unspoken connection between the viewer and the natural world represented here. The reflections in the water, and those lovely soft lines that bring texture to the foliage are captivating. Curator: I agree. It embodies a Romantic ideal, don’t you think? But looking closer, you really appreciate the precision of the pencil strokes. Think about the availability of art supplies at that time. Every choice the artist makes in rendering each reed and feather reflects intention. The drawing process itself becomes quite a significant form of labor to analyze. Editor: Absolutely. And thinking about landscape art historically, we see it emerge alongside shifts in land ownership and usage, like enclosure movements. Were those newly industrialized waterways accessible to the public, or privately controlled, excluding working class communities from leisure? Curator: An important point. This image, depicting working animals, perhaps romanticizes labour and industry without depicting labour itself. Van Borselen seems to have carefully crafted a scene divorced from human interaction. Editor: Yet the context of that missing labour speaks volumes! Also, there is a gendered reading to be done here, reflecting a passive female relationship to the picturesque as these drawings gained popularity with bourgeois women for private appreciation in the home. These drawings could act as signifiers for feminine accomplishments, status and the right type of leisurely contemplation, rather than the unseemly work of an outdoor sketch. Curator: Interesting. So the act of display and consumption is just as important to understand as the artwork itself. Editor: Precisely! The landscape is never just the landscape. It always invites discourse on access, labour, gender roles, and socio-economic power. It begs us to contemplate the narrative it carefully constructs, as much as it presents the subject, and that's what remains important to my understanding of Romantic art and what it reflects about this historical context. Curator: That gives me plenty to think about. Editor: As does a renewed appreciation for Van Borselen's precise use of materials to communicate his intention.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.