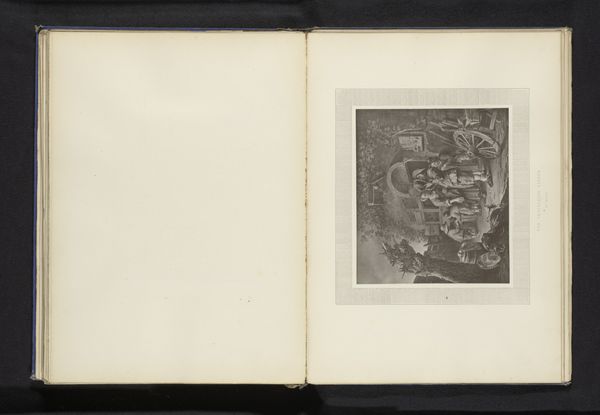

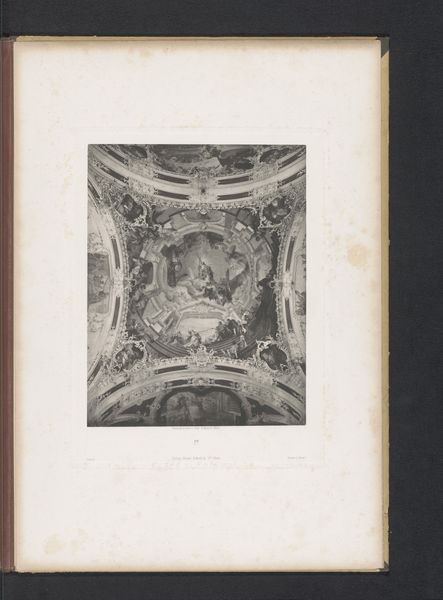

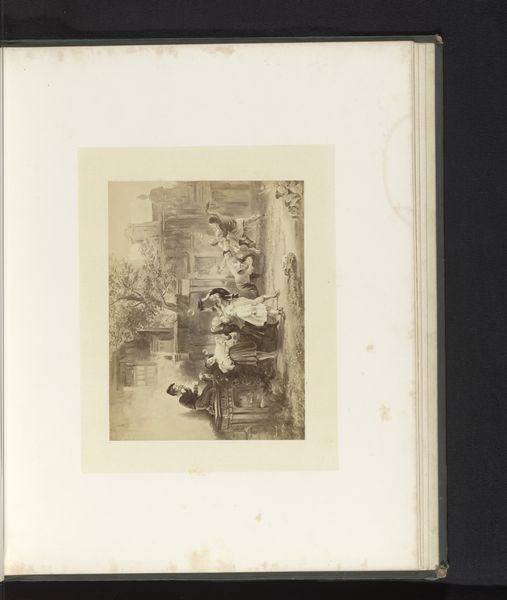

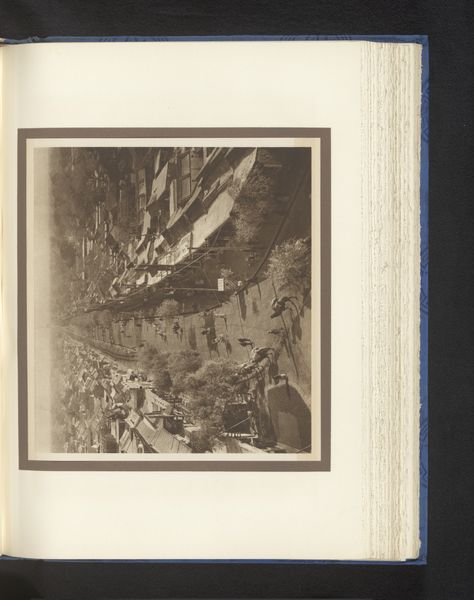

Detail van de fresco's in de kruisgang van de Dom van Bressanone, Italië before 1893

0:00

0:00

tempera, fresco, photography

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

fresco

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 189 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This photograph, taken before 1893 by Otto Schmidt, captures a section of fresco paintings within the Bressanone Cathedral cloister. It is a medieval narrative, with human figures occupying geometrically framed compartments. The symmetry gives it a balanced feel, but the figures within each panel are so active. How should we interpret this interplay between stillness and dynamism? Curator: Observe how the architecture and its painted decoration coalesce. The ribbed vaulting establishes the framework for the narrative. Let us consider this framework as a kind of armature that lends not just support but structure to the story-telling itself. Note the curvature, a subtle but vital element that echoes the viewer’s own bodily experience in the architectural space. The dynamism, as you astutely observed, stems from the counterpoint of active figures held within a rigorous matrix. How might the semiotics of space and form inflect our reading of this piece? Editor: I see what you mean. It's like the architecture is a language itself, dictating how we should 'read' the story. What do you mean by semiotics of space? Curator: Consider that the geometric frames, defined by the vaulting, create individual visual units, and by extension, individual episodes within the broader narrative. The repetition of this structural element establishes rhythm. The content and style of the frescos play into how one makes sense of that spatial syntax, the language of where figures are placed. Does it communicate importance or narrative order, perhaps? Editor: That makes a lot of sense! So, the dynamism comes from within the painted segments but the architecture, the rigid structure is integral to telling the story of what's happening inside. It’s not just decoration. I see how the interplay is what makes it art! Curator: Precisely.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.