oil-paint

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

genre-painting

#

rococo

Dimensions: height 35 cm, width 30 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

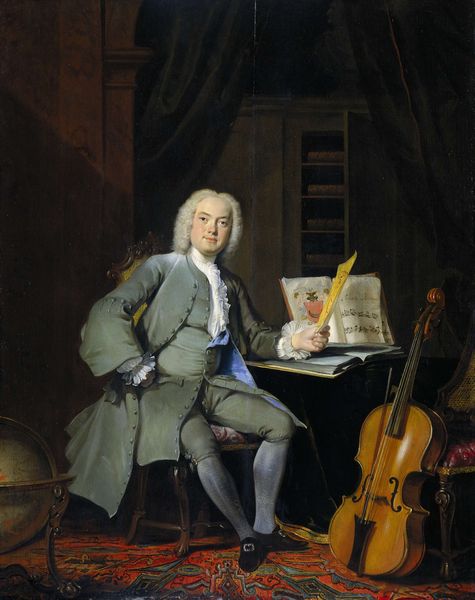

Curator: My first impression is a sense of contained energy. The engraver’s gaze is direct, almost challenging, but he's in this softly lit, domestic interior, wearing what appears to be a rather ornate dressing gown. Editor: This is *Portrait of the Engraver Jan Caspar Philips*, painted in 1747 by Tibout Regters. What strikes me is the way it seems to negotiate between public image and private sphere, typical of many portraits during the Enlightenment when professional identity became increasingly important. Curator: I get that. It's as if he’s caught between his work and a leisurely moment. He’s actively gesturing as if he’s explaining something – but his outfit whispers "relaxed intimacy." The cool color palette, that gray-blue, is lovely against the touches of muted rose in his robe. What do you see reflected about his societal role at the time, though? Editor: The choice of portraying Philips within his workspace, surrounded by the tools and products of his trade, really emphasizes the growing recognition of skilled craftsmanship within society. The engraving table, papers, and tools aren't mere props; they signify his professional standing. It subtly pushes the idea that the arts, even technical ones like engraving, are intellectual pursuits worthy of respect. It moved artisans a notch closer to, say, scholars and gentleman in public esteem. Curator: It’s wonderfully staged, isn't it? A little theatrical perhaps. I wonder if the window placement, framing him against the light, was meant to suggest a connection to inspiration, the "lightbulb moment?" A gentle, painterly touch permeates this oil sketch, creating a delicate sensibility to the moment—very Rococo! Editor: Possibly! But note too how different this intimate setting is to those of stately portraits designed to broadcast social position via wealth or political authority. There's an understated ambition at play here. Showing intellectual, rather than monetary or aristocratic prowess! He almost lures us in to become his eager student of arts! Curator: In looking at this, I consider not only his identity but also mine, now. We study this piece and interpret it over two centuries later. He and his contemporaries could not possibly grasp its enduring interest as cultural history. Editor: And that reflection highlights art's enduring dialogue with the present! Thanks to pieces like this portrait, we aren't passively admiring a face; we're engaging in a vibrant conversation about evolving notions of status and art history itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.