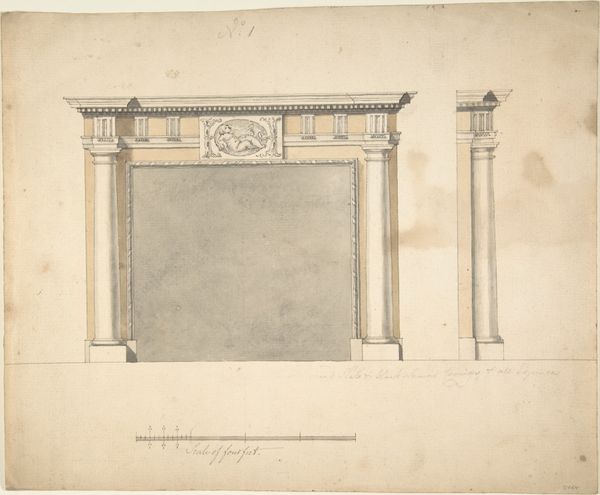

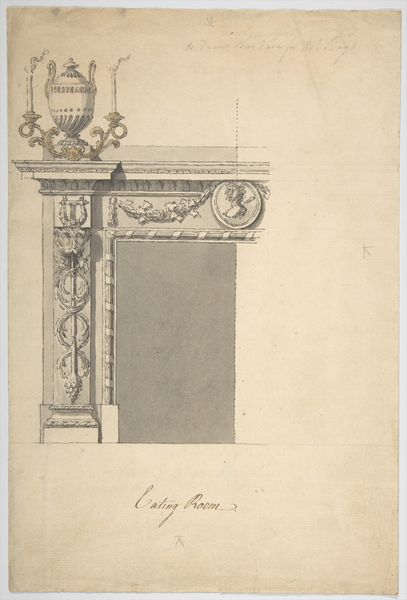

Design for a Chimney-piece, for Thomas Hollis of Lincoln's Inn, London 1754 - 1770

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, architecture

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

etching

#

architecture

Dimensions: sheet: 10 5/16 x 8 in. (26.2 x 20.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This meticulous drawing, executed between 1754 and 1770, offers us insight into the design process of Sir William Chambers. Specifically, it's a study for a chimney-piece intended for Thomas Hollis of Lincoln's Inn, London, rendered through etching and ink. What strikes you about it initially? Editor: Its formality is immediate. The carefully delineated architectural elements and neoclassical details—the garland, the bust—speak of power, aspiration, and, perhaps, a subtle control exerted through design itself. I see a stage being set for domestic life, where even warmth is curated. Curator: Absolutely. Chambers was a key figure in the Neoclassical movement in Britain, advocating a return to classical ideals of balance, symmetry, and proportion in architecture and design. His patrons often used these designs to showcase their education, wealth, and social standing. Editor: And I wonder, for whom was this hearth really intended to provide comfort? A design like this inherently excludes; it's a marker of status, reinforcing social hierarchies in a period rife with inequality. I'm drawn to that tension: a beautiful object designed to be exclusionary. Curator: Your point is well taken. Though intended for the private residence of Thomas Hollis, the design reflected the prevailing aristocratic tastes and political ideologies of the time. These designs helped normalize a particular aesthetic, and further entrenched power structures. Editor: Even the selection of Hollis as the intended recipient raises questions about his role in upholding those structures. What narratives of class and privilege are being cemented through the commissioning and ownership of such a piece? Curator: These architectural designs were meant to signal not only taste, but allegiance to certain Enlightenment ideals, selectively interpreted to reinforce established social norms. In the end it wasn’t made, this particular design remained on paper only. It's now an incredible drawing on display at The Met, reminding us that objects are never neutral; they carry the weight of history and social meaning. Editor: It really forces me to confront the uncomfortable realities of art and architecture as expressions of social power, as opposed to just beauty and aesthetics. It definitely makes me consider the legacy of these inequalities in our contemporary world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.