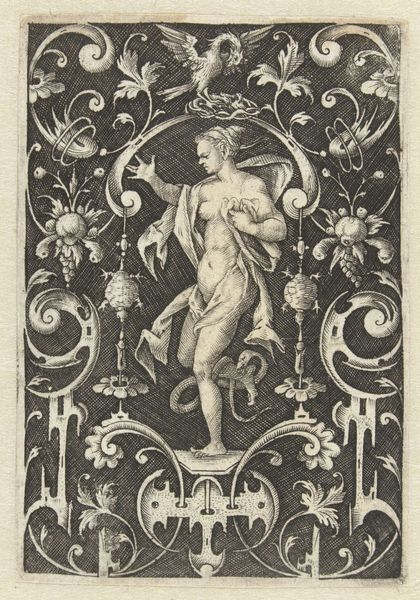

print, engraving

#

allegory

# print

#

old engraving style

#

mannerism

#

geometric

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 118 mm, width 77 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this engraving is called "Mars," made by Jacob Matham around 1597. The Rijksmuseum houses it. It's quite detailed, depicting the Roman god of war, but what strikes me is the almost industrial quality of the engraving itself, and its relation to allegorical representation. How can we consider its place within that context? Curator: Consider the materiality of printmaking in 1597. Each line, each gradation of tone, is the result of labor—the hand guiding the burin, the careful application of ink, the pressure of the press. Does that labor change our understanding of what Mars *represents*? Editor: Well, I guess it adds another layer. We're not just seeing a god of war, but also the product of human effort. Is Matham drawing attention to the commercial production of art itself? Curator: Precisely! Look at the repetition within the image - the patterned lines that build up form. Are these purely aesthetic decisions, or do they mirror a broader trend towards mass production that was beginning to emerge? Where did Matham source the materials needed for engraving? Editor: It's like seeing both the classical ideal *and* the means of its distribution combined in one piece. Maybe this engraving offered wider access to classical figures beyond, say, painted works exclusive to wealthy patrons. Curator: Good point. Who had access to prints, and how does that accessibility impact our understanding of Mars's power? We often think of power in terms of military might. Editor: It democratizes the image itself. It connects ideas of Mars, of conflict and militarization, with commercialism and early forms of distribution and the labour required to produce these works. I’d never thought about that so explicitly. Curator: And hopefully, you now have new paths for engaging with images from the early modern period. The making matters just as much as the message.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.