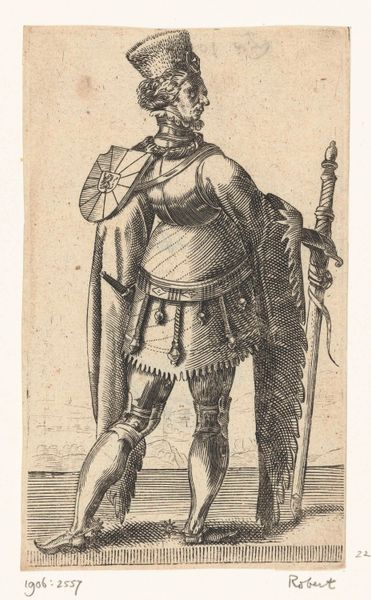

Portret van Willem VI van Beieren, graaf van Holland en Zeeland 1620

0:00

0:00

adriaenmatham

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

medieval

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

caricature

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 130 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Adriaen Matham’s 1620 engraving, "Portret van Willem VI van Beieren, graaf van Holland en Zeeland," currently at the Rijksmuseum. The detail is astonishing. It's striking how vulnerable Willem seems from behind, despite all the armor. How do you read this portrait, seeing him depicted this way? Curator: I find it fascinating how Matham plays with power and vulnerability. The figure's back faces us, yes, but the towering helmet plume, the ornate shield – these are blatant markers of aristocratic status, amplified for consumption. What is interesting here is understanding how images of power work – how identities are built and performed via dress, symbolism and societal expectation. Are these visual claims to power inherently precarious? Editor: Precarity, yes, especially as he isn't facing us! Why choose this angle? Was this a typical choice for portraying nobility? Curator: Often, portraits aimed to project invincibility. Depicting Willem from behind potentially subverts that expectation. Consider the historical context. What anxieties or power dynamics within the Dutch Golden Age could explain this choice? Maybe this speaks to a deeper crisis of legitimacy. Even the "Dutch Golden Age" rings hollow given it was built on exploitation and the labor of the working class. Editor: I hadn't thought of it that way, seeing vulnerability as potentially communicating the anxieties of those in charge rather than weakness. It feels more subversive than honorific. Curator: Exactly! Think about who this print was intended for. Was it meant to celebrate Willem, or perhaps subtly critique him and the social order he represented? The act of circulating an image itself carries social and political weight. Editor: This conversation really shifts my view of this portrait! It’s made me rethink how we automatically perceive power through portraiture. Thanks so much for your insights! Curator: The pleasure is mine! Looking critically at the images surrounding us allows for a much deeper understanding of the intersectional history we live in.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.