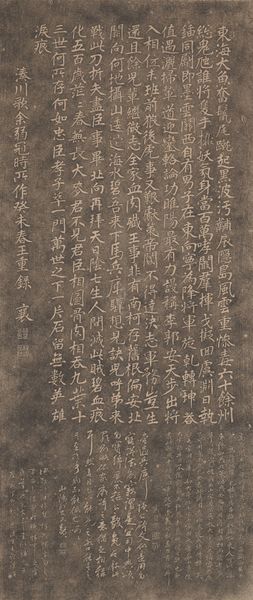

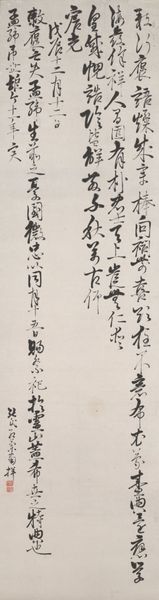

drawing, paper, ink-on-paper, hanging-scroll, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

japan

#

paper

#

ink-on-paper

#

hanging-scroll

#

ink

#

geometric

#

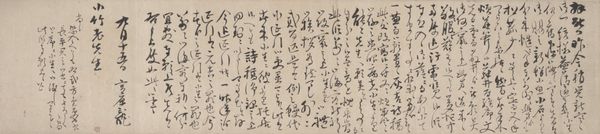

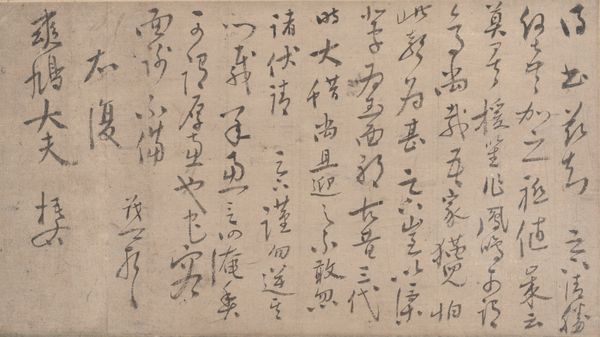

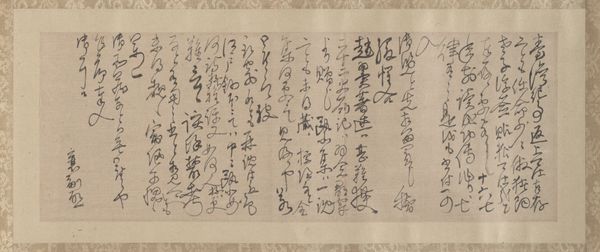

calligraphic

#

line

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: 50 7/8 × 22 15/16 in. (129.22 × 58.26 cm) (image)73 3/8 × 24 7/16 in. (186.37 × 62.07 cm) (mount, without roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

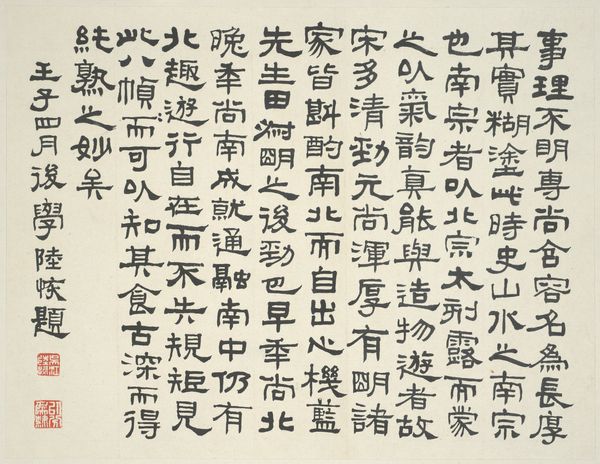

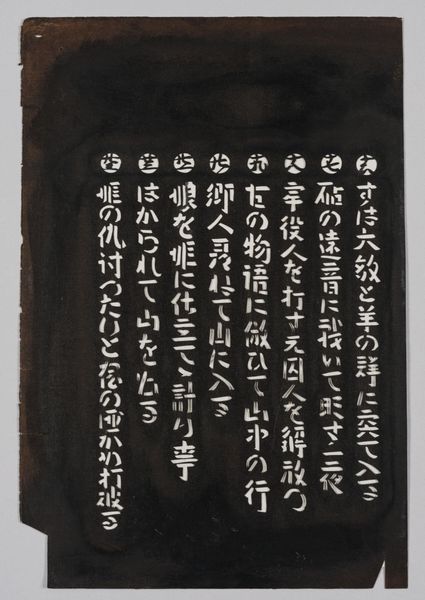

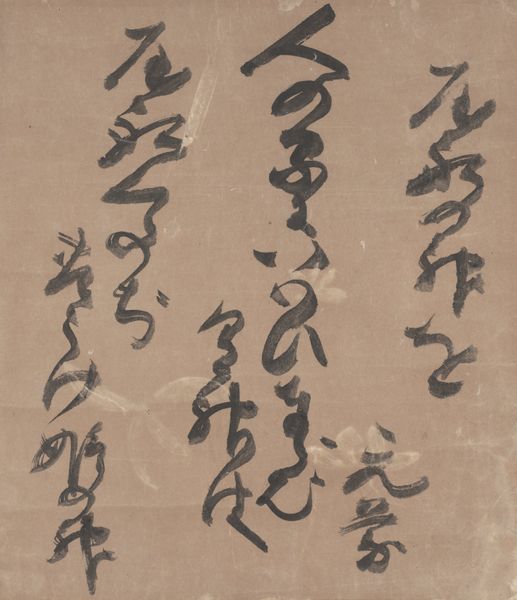

Curator: Here we have Fujita Tōko's "Poem of 1849," a hanging scroll crafted with ink on paper, a striking example of Japanese calligraphy housed at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: My first impression? The intense density. The characters cascade down the paper like a waterfall, each stroke deliberate but urgent. It's quite imposing, really. Curator: Absolutely. And what makes it compelling is considering the process, right? The way Tōko meticulously controlled the flow of ink to achieve the balance between solid form and ethereal quality. The paper itself would have been carefully prepared, its texture influencing each brushstroke. Editor: Indeed, and looking at it through a lens of 19th-century Japanese socio-political conditions, it raises fascinating questions about the role of intellectuals and artists during periods of upheaval. The poem itself surely carries layered meanings. It might have encoded the author's stance towards various contemporary events or political views during the late Edo period in Japan. What could have motivated him? Curator: Undoubtedly, access to materials like high-quality ink and paper were influenced by class structures and trade networks, connecting the artwork directly to the economic realities of the time. Even the act of displaying the hanging scroll in a home was laden with social significance. Editor: And the choice of calligraphic style certainly signals particular ideologies. In the intricate web of symbols it employs, this poem transcends mere visual appeal to operate as a poignant statement of identity, a reflection on self, purpose, and perhaps even rebellion in 1849 Japan. We see visual rhythm married to personal and national sentiment here. Curator: Considering all these details reveals that appreciating it beyond the surface invites conversations on the labor, networks, and values invested into making an art object. Editor: This artwork invites us to think deeply not just about Tōko’s intentions, but about the ongoing dialogues concerning freedom of expression and social responsibility— issues just as critical today as they were in 1849.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

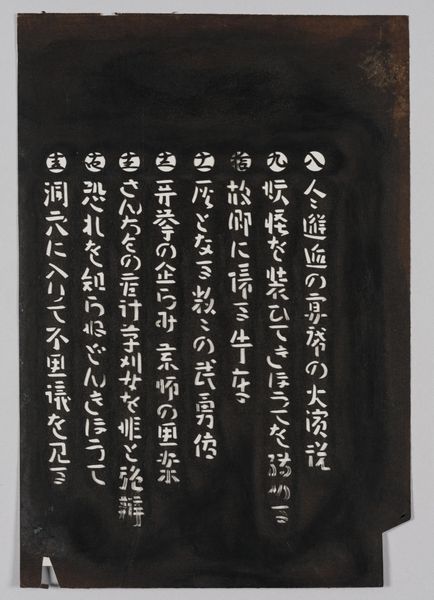

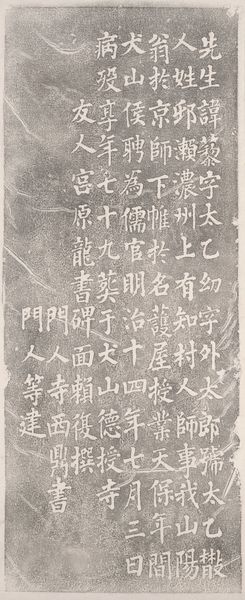

This work is a rubbing, an impression of inscriptions carved into stone made by placing a sheet of moistened paper over the surface and tapping with a ball of cloth soaked in ink. For centuries, rubbings played an important role in transmitting calligraphy because it allowed for accurate reproductions of not just the content but also the writing style. This work preserves a poem by Fujita Tōko, a Confucian scholar. Fujita was exiled in 1844 when his lord Tokugawa Nariaki was forced into retirement. In the poem, Fujitaexpressed his devotion to the cause of restoring power to the Emperor, a sentiment that ultimately grew among samurai and led to the Meiji Restoration.三決死矣而不死,二十五回渡刀水。五乞閒地不得閒,三十九年七處徙。邦家隆替非偶然,人生得失豈徒爾。自驚塵垢盈皮膚,猶余忠義填骨髓。嫖姚定遠不可期,丘明馬遷空自企。苟明大義正人心,皇道奚患不興起。斯心奮發誓神明,古人有雲斃而已。Three times [I was] prepared to die, but did not.Twenty-five times [I] crossed Tōsui [Tone River].Five times, [I] sought a quiet place [to retire] but did not obtaincarefreeness.In thirty-nine years I moved to seven places.The rise and decline of a state is not by chance.How could the achievements and disappointments of life betrivial'The dust and filth that covers [my] skin surprises me.The loyalty and justice that still remains fills my whole bone andmarrow.Do not expect Piao Yao and Ding YuanVainly plan by myself like Qiuming and Maqian*If [I can] reveal the great cause and rectify the human spiritThere is no worry that the way of the Emperor will not begin again.This spirit is stirred; I pledge to the gods.As the ancients say: [I am determined to fight] until my dying day. Huo Qubing (140 bc–117 bce), Chinese general Ban Chao (32–102 ce), Chinese generalZuo Qiuming (556–451 bce), Chinese historian who wrote The Commentaryof Zuo (Zuo Zhuan)*Sima Qian (c. 145–c. 86 bce), Chinese historian who wrote the Records of theGrand Historian (Shiji)

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.