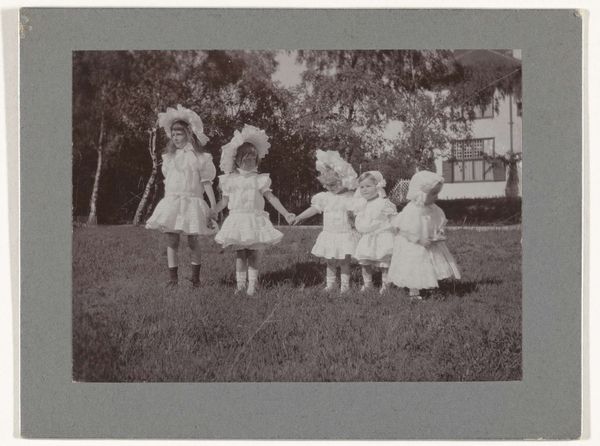

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 5.5 cm, width 5.5 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me is the composition, the figures seemingly almost swallowed by the long grass. Editor: And what is it about, specifically? Curator: This gelatin-silver print, currently held at the Rijksmuseum, is titled "Groep Nederlanders en Duitse militairen," or "Group of Dutch People and German Soldiers." It was produced by an anonymous artist, likely sometime between 1940 and 1946. It looks to me as if people, collaborators perhaps, are attempting to enjoy a sunny day. It’s incredibly uneasy, in the light of history. Editor: Yes, that initial sense of idyllic relaxation curdles when you consider the historical context, and that these people seem to be coexisting quite comfortably. Are we certain these are German soldiers, though? Curator: Uniforms aren’t visible, and identification can often be challenging with photography. Regardless, the backdrop is almost classically bourgeois; the nice lawn, the house. It speaks to notions of occupation, class, and complicity. Editor: The printing process also becomes significant here. The gelatin silver print was widespread then, but its status as both a means of mass communication and artistic medium is what catches my eye. Photography allows us to reflect upon material traces of historical complexity, captured from the artist. Curator: Precisely. The choice of representing a difficult moment in a rather standard, almost banal manner actually amplifies its effect. I am always struck by how art engages with these everyday aspects of life amidst vast historical movements. Editor: Yes, a photograph is the material record of an instant. Its presence and circulation after being printed reflect that reality. Curator: This image isn't celebratory, nor overtly critical. It occupies a morally gray space, making it deeply compelling. Editor: For me, the physical print embodies a past we still grapple with, and I will ponder the role it played as both document and, perhaps, propaganda.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.