![[Earthworks in Interior of Fort Mahone, in Front of Petersburg, Virginia] by Timothy O'Sullivan](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2E5NjU2NDdiLWU2NTItNDk5Ny04YTAxLTg4ZTRiYjE3NDFmZi9hOTY1NjQ3Yi1lNjUyLTQ5OTctOGEwMS04OGU0YmIxNzQxZmZfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

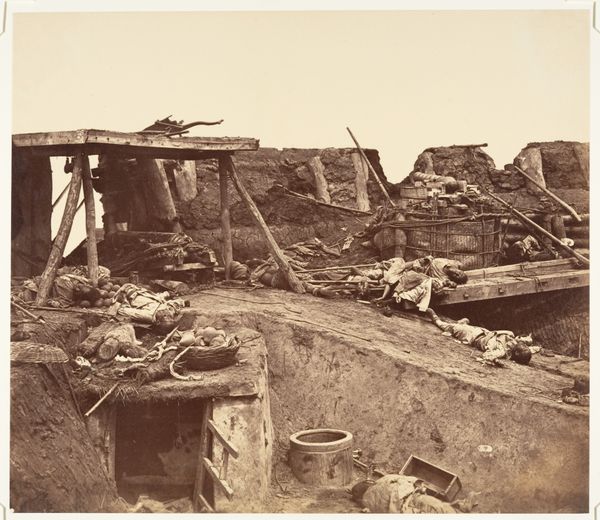

[Earthworks in Interior of Fort Mahone, in Front of Petersburg, Virginia] 1865

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

black and white photography

#

countryside

#

war

#

landscape

#

nature

#

photography

#

outdoor scenery

#

nature friendly

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

nature heavy

#

nature environment

#

outdoor activity

#

monochrome

#

shadow overcast

Dimensions: 16.3 x 21.3 cm (6 7/16 x 8 3/8 in. )

Copyright: Public Domain

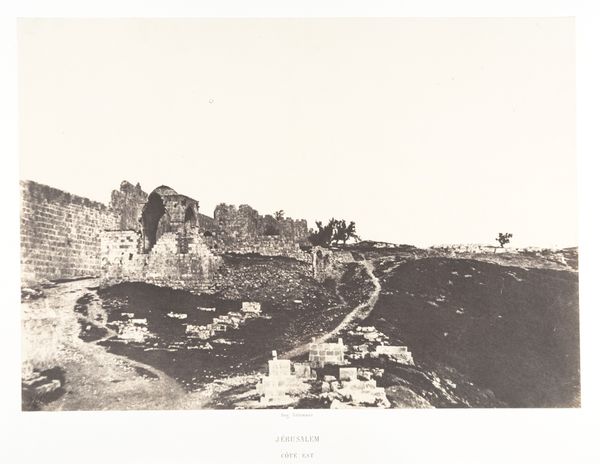

Curator: This photograph, a gelatin-silver print, is titled "[Earthworks in Interior of Fort Mahone, in Front of Petersburg, Virginia]" by Timothy O'Sullivan, taken in 1865. Editor: Man, it’s bleak, isn’t it? That monochrome almost feels like staring into the face of…absence. An emptiness, with these rough fortifications like…scars on the land. Curator: It's interesting that you describe them as scars, as sites of trauma. Situated in 1865, it resonates with the closing chapter of the American Civil War, a period where landscapes themselves became texts of conflict, imbued with meanings of division, resilience, and, ultimately, reconstruction. Fort Mahone, one of the Confederate strongholds, stands here as both a physical structure and a representation of ideological entrenchment. Editor: Exactly! And those little wooden boxes strewn about the foreground? They look discarded, forgotten, like remnants of a game no one won. A terribly grim game at that. Is it just me, or does the overall composition feel intentionally unbalanced, adding to that sense of unease? Curator: I think your impression is quite astute. O'Sullivan's choice to photograph the fort's interior rather than the exterior might signify a concern with the interiority of conflict itself, shifting attention from grand narratives to the more intimate consequences on lived spaces. Furthermore, that focus on what feels ruined points towards larger social inequalities as a consequence of the Civil War, its impact rippling across class, race, and gender lines, disrupting established norms, particularly in the lives of women. Editor: It's weird... usually landscape photos have some element of solace. Here it is just, ugh. It makes me consider the labor that went into creating these works – a visual embodiment of conflict, reshaping land and life. What remains speaks to labor and loss, doesn't it? Curator: It absolutely does. What seems like mere absence in the photograph also highlights a painful legacy—a disruption in labor structures and racial terror as war's devastating undertow. The photograph thus demands that we consider it as more than just documentation; rather, it functions as a form of witnessing. Editor: Definitely leaves a chill. But hey, isn’t that what great art does—stirs up something real and sometimes uncomfortable inside you? Curator: Precisely. It encourages critical awareness of history, offering, in turn, ways to interpret the reverberations in our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.