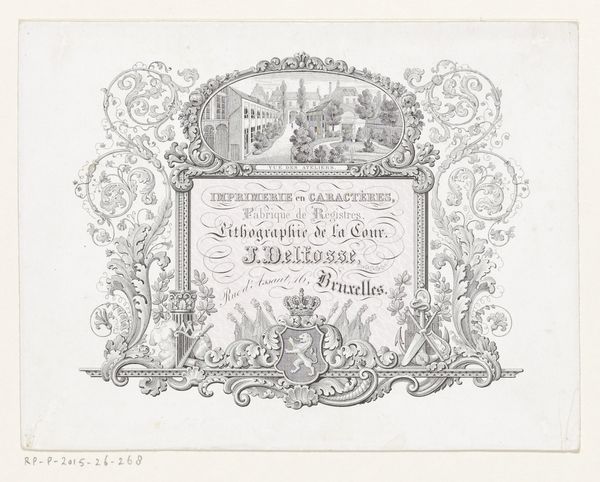

Ter Nagedachtenis van hare koninglyke hoogheid Frederika Louisa Wilhelmina (...) in leven Koningin der Nederlanden (...) Possibly 1837

0:00

0:00

asteenbeek

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

etching

#

history-painting

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

#

miniature

#

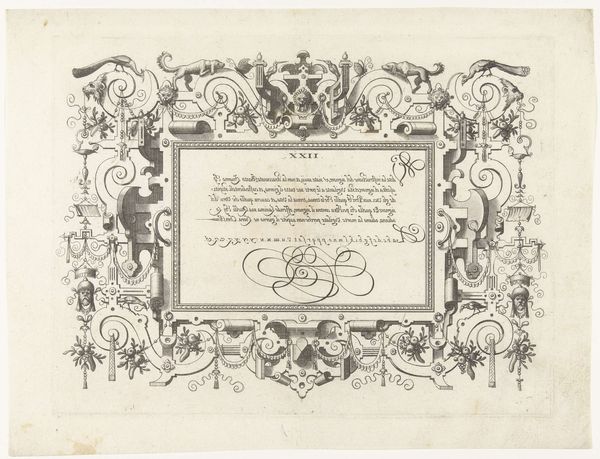

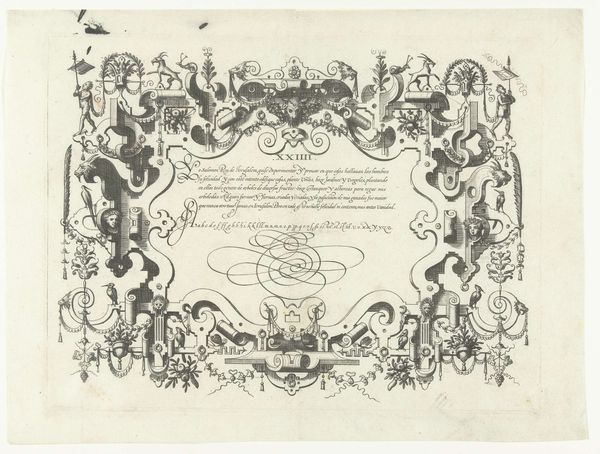

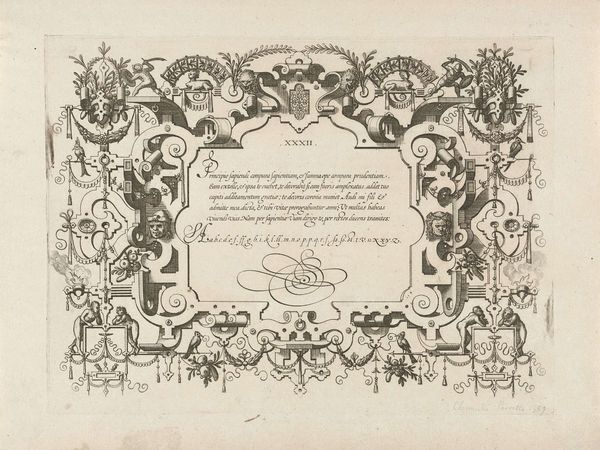

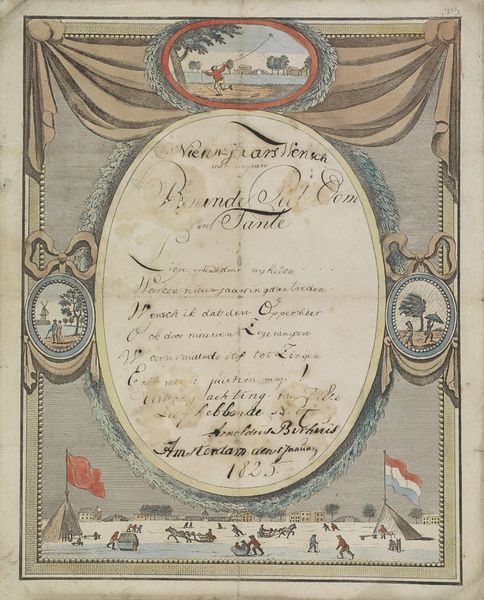

calligraphy

Dimensions: height 423 mm, width 536 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

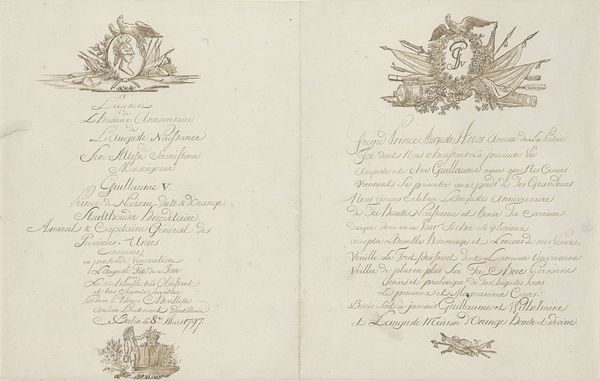

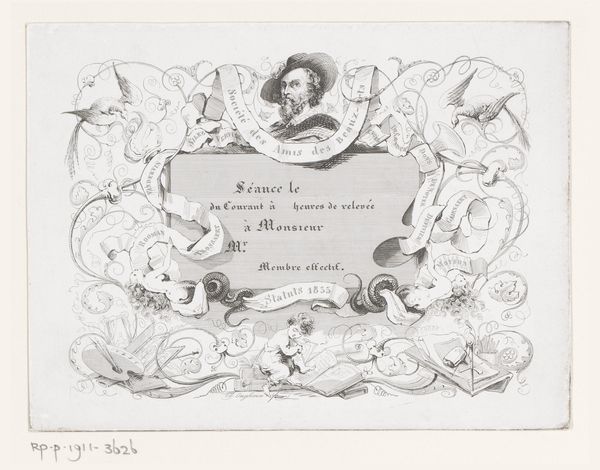

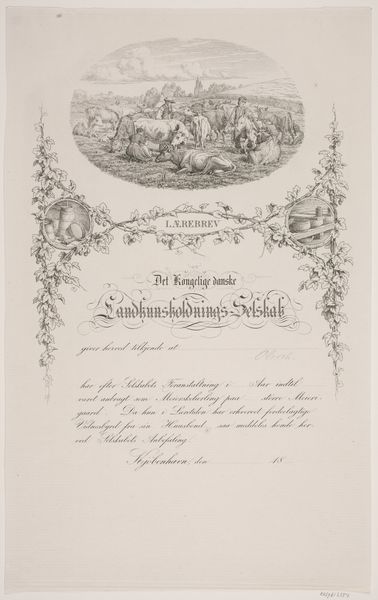

Curator: Take a moment to observe this engraving, likely from 1837. It's titled "Ter Nagedachtenis van hare koninglyke hoogheid Frederika Louisa Wilhelmina (...) in leven Koningin der Nederlanden (...)" which translates to "In memory of her royal highness Frederika Louisa Wilhelmina (...) in life Queen of the Netherlands (...)." The piece resides here in the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It’s beautiful, but also incredibly ornate. The calligraphy itself becomes the primary focus; it’s so interwoven with the decorative flourishes. I feel a real sense of formality, of course, but almost to an overwhelming degree. Curator: Yes, the materiality of the piece speaks volumes. It's an etching, an engraving on what appears to be paper. Consider the labor involved in such detailed work, the deliberate crafting of each line to convey both text and imagery. This wasn't mass-produced; it's a testament to skilled craftsmanship. Editor: Precisely. This wasn’t made for mass consumption, yet its purpose is commemorative, to share the legacy of the Queen. The tension between the intensive labor and its public role interests me. What political and social narratives did it aim to solidify, especially considering its function after the Queen's death? How many were made, and for whom? Curator: That's where it gets interesting. As a print, it suggests wider circulation than, say, a unique painted portrait. Yet, its style aligns with decorative arts, perhaps intended for display in homes or institutions that sought to publicly mourn and respect the Queen. It’s not necessarily ‘high art’, blurring the boundaries with craft and commemorative ephemera. Editor: I agree. And who commissioned it matters too. Was this state-sponsored grief, or did the market demand these kinds of personalized mementos? Also, notice the lettering style. This is such beautiful calligraphy but at a time of burgeoning industrialized print media. Curator: The identity of A. Steenbeek, listed as the artist, could give us clues. Their role—were they artisan, commissioned artist, or part of a workshop churning out commemorative pieces—can reveal more about the political economy of grief at the time and the status of printmakers. Editor: Looking at this work gives me a sense of a society navigating new modes of public emotion alongside traditional artistic practices. It's a reminder that even seemingly straightforward commemorative objects are deeply embedded in the socio-political fabric of their time. Curator: Indeed. For me, the piece serves as a powerful testament to how social values and craft intersect, producing a tangible artefact that both mourns an individual and solidifies a reigning power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.