painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

venetian-painting

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

child

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 247 x 133 cm

Copyright: Public domain

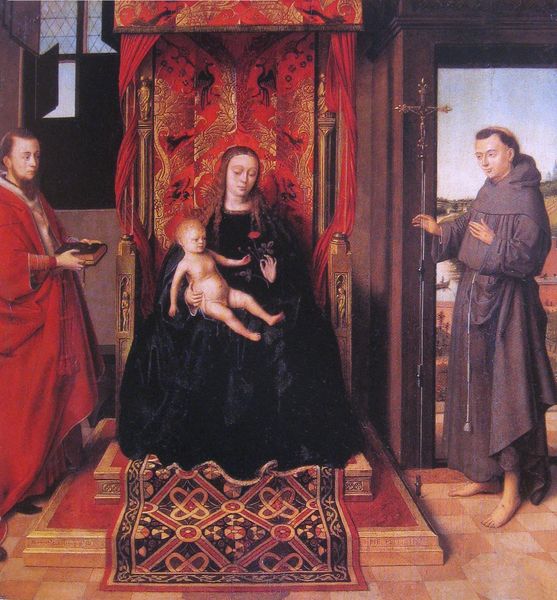

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this arresting image of father and son. Painted in 1552 by Paolo Veronese, it's entitled "Iseppo and Adriano da Porto" and it hangs here in the Uffizi. Editor: Whoa, they are swathed in opulence! The velvet, the fur—I feel like I've walked into a winter palace, but rendered in rich Venetian hues. The father looms; the boy looks fragile. It’s intriguing. Curator: Indeed. These garments weren’t just chosen at random. The da Porto family were part of the Venetian elite, successful merchants, and these lavish clothes, though surely quite uncomfortable, declared their status and wealth for all to see. It’s a highly performative display of power. Editor: It's also interesting to consider the artist playing a role in boosting that display. It speaks volumes about the culture of art as promotion at the time, where these luxurious textures became brushstrokes celebrating commerce. Curator: Precisely! Veronese secured important commissions from families like the da Porto partly through his adept ability to capture the textures and details that reflected wealth and status. Also, this intimate moment belies the formal conventions of portraiture during the High Renaissance. While there’s an undeniable affection, there’s still a clear message of lineage. Editor: And what about that key on a golden cord that hangs on the little boy? That’s a potent symbol; what does it unlock? Or perhaps, more accurately, what future doors is it supposed to open? Is the weight of expectation written on his small face? It gives the portrait an undeniable air of constraint. Curator: The key symbolizes a high-ranking status within Venetian society and implies a prominent role within their family life, suggesting a position of authority and future prospects tied to their lineage. But the painting doesn't just declare status; it perpetuates it. Portraits like these solidify the place of families within the social order. They present an ideal of themselves for public and future generations. Editor: Thinking about legacies gives me pause; even through these layers of representation, that intense human connection lingers. That look the child gives, holding on to his father like a lifeline—those are powerful! We're witnessing not just an emblem of class, but perhaps the start of what binds a person's individual story to all that. Curator: Absolutely. By bringing both formal conventions and genuine affection together, the artist provides an entry point for audiences even today. That ability to speak to us across centuries makes the portrait compelling. Editor: I concur! Who would've thought a pile of velvets could say so much?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.