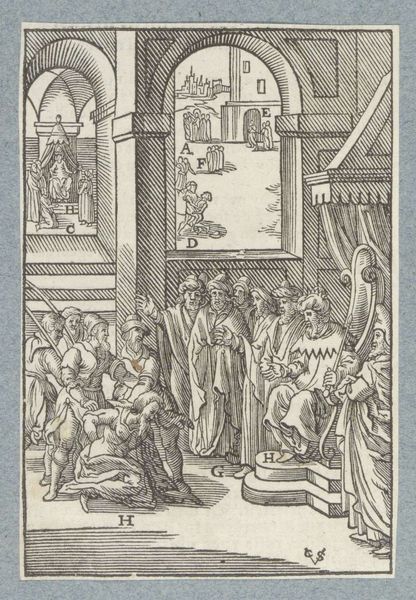

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pen illustration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 112 mm, width 84 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

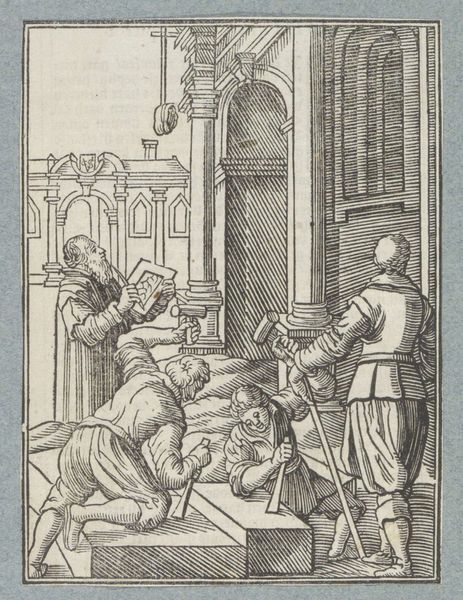

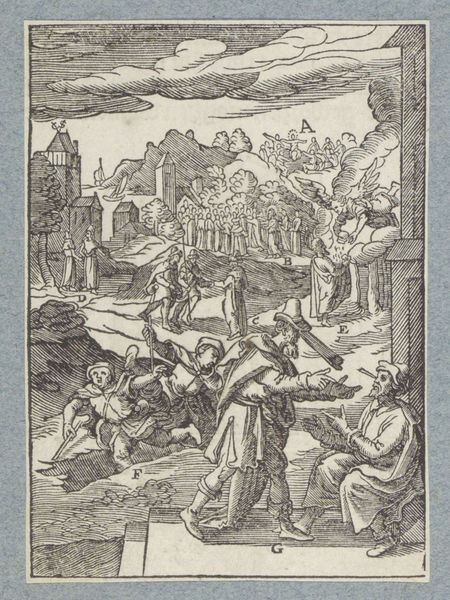

Curator: Right now, we’re standing in front of a black and white engraving by Christoffel van Sichem II, dating from 1645-1646. The Rijksmuseum calls it "Tobit begraaft een dode man," or "Tobit burying a dead man." Editor: My first thought? Stark. Really emphasizes the solemnity of the moment. It’s amazing how much detail he gets from just lines. The composition seems meticulously crafted. Curator: Yes, the meticulous craft speaks to the production, the labor, you know? Think about the process: the woodblock carving, the pressure applied for each impression… It’s a physically demanding and repetitive task, but each print could spread the story further. Editor: True. It's part of the genre-painting theme, but it pulls directly from narrative art, like a captured memory. The way he rendered those robes—especially Tobit's—they feel so heavy, almost weighted down with sorrow. Does that resonate with you? The man at the center giving final rites before burial. Curator: Absolutely. And if you look closely, you’ll see he includes fine architectural elements in the background—like he’s trying to frame this quiet scene of human kindness amidst worldly complexity and history. I keep wondering what the engraver's relationship to that architectural labor might have been. Editor: That's interesting because Tobit risked execution, an immense sacrifice rooted in community. Maybe Sichem knew the realities of such precarious labor too. What also catches me is how little emotion is expressed. It’s somber but, restrained. What do you make of that? Curator: Maybe the artist’s striving for objectivity within genre paintings reflects a burgeoning shift toward representing humanity as it is, even in the face of mortality and societal constraints, that reflects the artist’s mindset? Like the materials, it’s a meditation on simple labor that makes human history. Editor: Looking at this from a social point of view allows us to reframe the narrative. The print underscores social values during the 17th century. Curator: And also to recognize the skill and effort inherent in the artistic material process, as if imbuing each print with a measure of silent activism that lives to this day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.