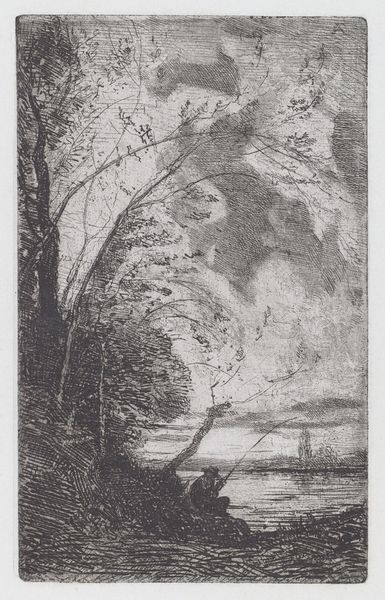

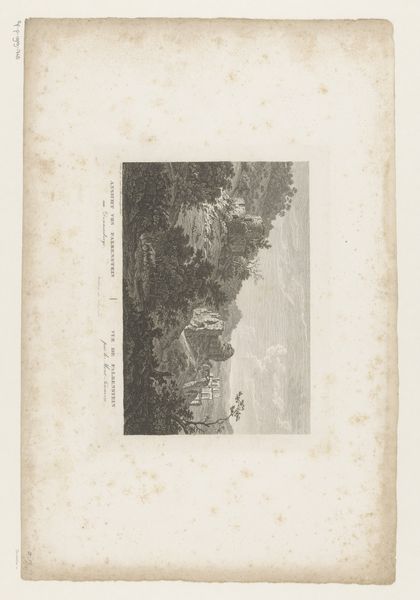

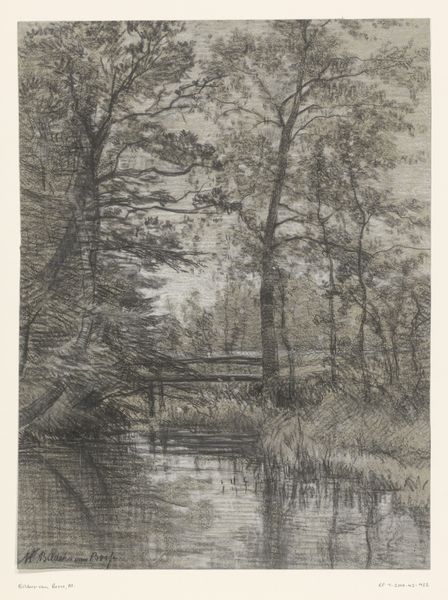

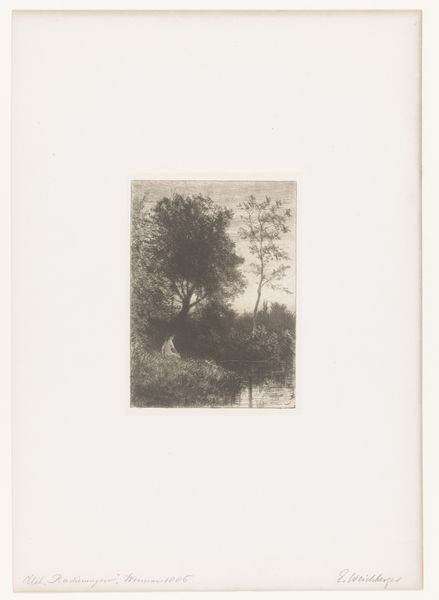

Dimensions: Image: 16.5 × 13.8 cm (6 1/2 × 5 7/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Immediately, I’m struck by the hushed, ethereal quality of this photograph. The tonal range is quite limited, lending it a dreamy, almost melancholic air. Editor: That's interesting. You are responding to the atmosphere. Allow me to introduce you to the image in more detail. This gelatin-silver print, entitled "The Upper Lake", was taken between 1853 and 1856 by James Knight. What is fascinating is that we encounter an artwork capturing the intersection of photography and romantic landscape aesthetics. Curator: Yes, I notice the echoes of the Romantic movement, with nature depicted as something sublime, untamed. But I’m curious, who was Knight? Was he consciously placing himself within the visual rhetoric of romanticism? Or might this simply reflect the cultural milieu he inhabited? Editor: That's exactly the question that animates my inquiry. James Knight, active primarily in the mid-19th century, inhabited a world of rapidly evolving artistic and scientific approaches to rendering landscape. While not as widely known, his engagement with the medium reveals so much about how photography began to be recognized as an aesthetic vehicle during the Romantic era. One could further explore the relationship to artists of the Hudson River School. The location itself, likely the Northeastern United States, evokes very particular nationalistic associations during that time, and perhaps, notions of expansionism or preservation. Curator: It also appears to connect with environmental discourses present today. Given the history of extraction and industrialization during that period, I wonder whether there is a trace of criticism or a nostalgic appeal to simpler times within these images. The choice of vantage point and composition appear deliberate, almost like an attempt to idealize and romanticize what was already in decline due to human action. Editor: This provides an excellent framework for looking closely at landscape, not only as visual records but as social documents that reflect ideologies around national identity, use of land, gender dynamics, class conflicts and so on. This work serves as a fascinating time capsule into that era. It makes me question whether any depiction of nature can truly exist independently of cultural or political ideology. Curator: Precisely. Examining the choices made – subject matter, technique, even the very act of documenting a specific location – can offer rich insight into the relationship between society and the natural world, then and now. Editor: So very well stated. I feel as if I am equipped with many questions to think through during my next visit!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.