print, photography

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

sketch book

#

hand drawn type

#

landscape

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

journal

#

photojournalism

#

fading type

#

thick font

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 205 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

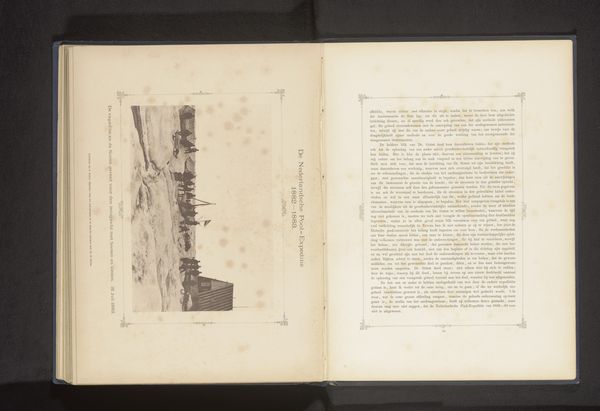

Editor: This image presents a page from a sketchbook, featuring a photographic print titled "Gezicht op de Varna in de haven van Trondheim," taken before 1886, by H. Ekama. The aged paper and hand-drawn typeface surrounding the photograph give it an intimate, almost journal-like quality. What story do you think this sketchbook page tells about the relationship between art, travel, and knowledge in the 19th century? Curator: It speaks volumes, actually. Consider the Dutch Golden Age revival influences visible here in photography. The sketchbook, conceived as a personal repository, became a vital tool for documenting expeditions. This blend of photography and hand-drawn typography highlights the burgeoning role of visual evidence in shaping public understanding and historical narrative. It also asks what was admissible as “truth.” Notice the frame around the picture; does it signal any particular meaning, as separate from other sketches in the journal, for instance? Editor: That’s interesting. The framing does draw attention to the photograph as a distinct element. Perhaps it signifies its importance as a primary source, validated and displayed like an exhibition piece even within the private context of the sketchbook? Curator: Exactly. Think about who would create, possess, and engage with such a book? It suggests an educated, probably wealthy audience. Further, the framing, along with the meticulous labeling, elevated the photographic image to a level of documentary credibility, helping to cement photography’s place in scientific and cultural institutions. These types of “exhibitions” allowed people who were otherwise limited a view of these images. Editor: That makes me wonder, how much did these visual records shape the colonial gaze, influencing perceptions of the places and people documented? Curator: That’s a crucial question. It urges us to examine the politics embedded within these seemingly objective images, and to interrogate the power dynamics inherent in the act of documentation and dissemination. It serves to reevaluate photography’s public role as both an artistic and a political tool of knowledge. Editor: I’m walking away seeing how one artifact can reveal broader narratives about art, society, and the politics of seeing. Thank you. Curator: Likewise. It's a reminder of art's power to engage critical thinking about the stories we tell ourselves about the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.