Emperor Nicolas working in his cabinet, plate 94 from Actualités 1850

0:00

0:00

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

drawing

#

lithograph

# print

#

caricature

#

caricature

#

cartoon sketch

#

paper

#

france

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 208 × 269 mm (image); 259 × 334 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

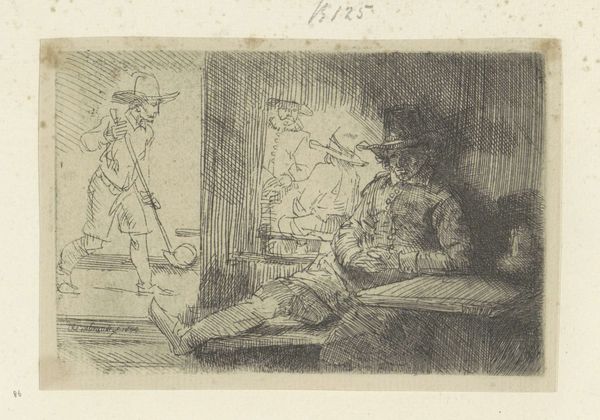

Curator: Welcome. Today, we are looking at Honoré Daumier's 1850 lithograph, "Emperor Nicolas working in his cabinet, plate 94 from Actualités," currently held in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: My initial impression? Utter chaos. This man, this "Emperor Nicolas," seems consumed by...something. He's trampling a map of France, wielding a sword, surrounded by shadowy figures. The entire image exudes turmoil. Curator: Indeed. Daumier frequently employed caricature to critique political figures and social mores. This lithograph uses Nicholas as a symbol, likely to tap into contemporary anxieties regarding power and governance within France and its relations to the rest of Europe at the time. Editor: Ah, so it’s not necessarily a literal depiction of the Emperor Nicolas of Russia, but a stand-in, represented through this frenetic style, clearly reproduced from a stone matrix onto paper. How many impressions were made, do we know? Curator: Hard to be sure exactly how many lithographic impressions were made, but Daumier's political cartoons appeared regularly in the Parisian press. The repeated image in print speaks to an intention to broadly disseminate and perhaps to affect public sentiments on matters of governance and national image. The maps as motifs... Editor: They’re powerful symbols, aren’t they? A subjugated France, represented by a map on the floor. And two other maps hang behind the Nicolas figure, which echoe the composition of other people standing behind him. I find myself thinking about borders – how they are made, contested, redrawn… all very material processes driven by power. Curator: Precisely. Maps were understood as expressions of ownership, a visualization of control. Notice how Daumier employs such graphic intensity, with dark lines and shading—heightening the sense of unease and distortion, not unlike Goya's prints during times of crisis. This lends an apocalyptic vision of impending doom to this scenario, while functioning on multiple levels of symbol. Editor: There’s a visceral quality to this print; Daumier's skill lies in conveying the instability of the time, and also of the moment itself when a graphic artwork emerges. It reminds us that even seemingly permanent representations can reflect a state of flux and constant change—printed, circulated, handled… politicized. Curator: Absolutely, a potent blend of symbolic meaning and material impact. Editor: Indeed, art history, at its best, is about how process becomes a sign.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.