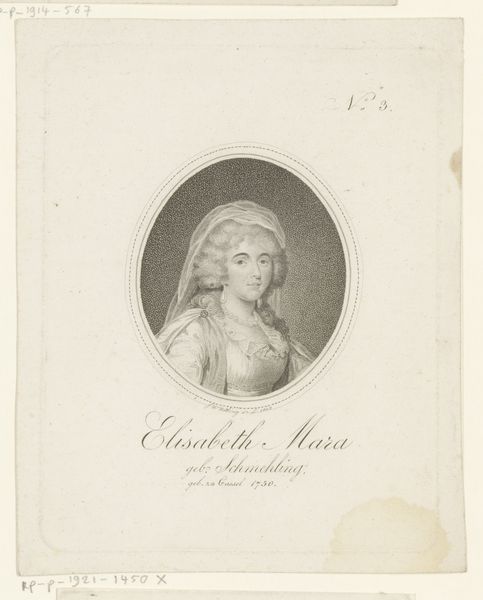

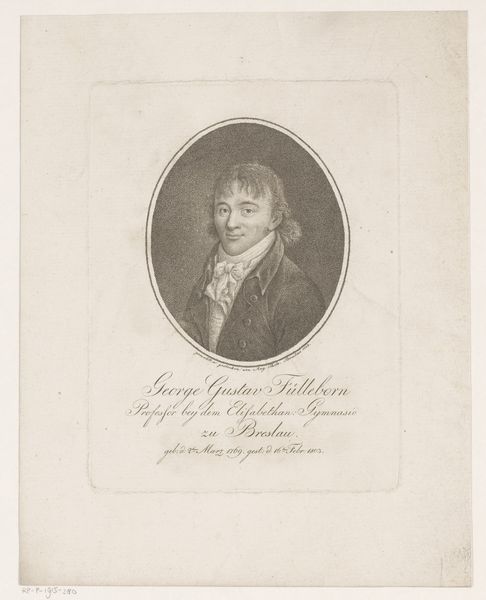

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

paper

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 173 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have an engraving, “Charlotte Wilhelmine Krünitz,” created around 1790-1791 by J.S.L. Halle. It's a print on paper and has a decidedly Neoclassical feel. The portrait feels quite formal, almost like a document. What strikes you most about it? Curator: Considering the period and the subject matter, it's important to view this within the context of the emerging middle class and their aspirations for social visibility. Portraiture, historically a privilege of the aristocracy, became a tool for self-representation for the rising bourgeoisie. Editor: That’s interesting! So this engraving served a purpose beyond just commemorating her image? Curator: Absolutely. The formal pose, the Neoclassical style referencing classical ideals, and the very act of commissioning and displaying such a portrait, all contributed to constructing and communicating a certain social standing. This print, accessible to a wider audience than an oil painting, democratizes portraiture. Notice the inscription below, detailing her birth and other milestones – it's almost like a public record, isn't it? Editor: I see what you mean. It's a public declaration, in a way. I hadn't considered how printmaking allowed for broader societal participation in portraiture. Curator: Indeed. Ask yourself, how did the proliferation of printed images alter social dynamics, or even the very concept of fame? Editor: This gives me a whole new perspective on how to read portraiture from this era! It's more than just an image; it’s a statement of societal shifts. Curator: Exactly. Context transforms an image into evidence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.