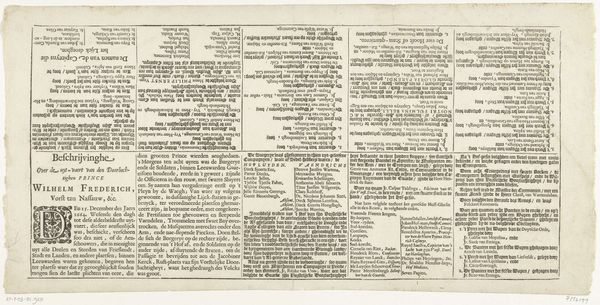

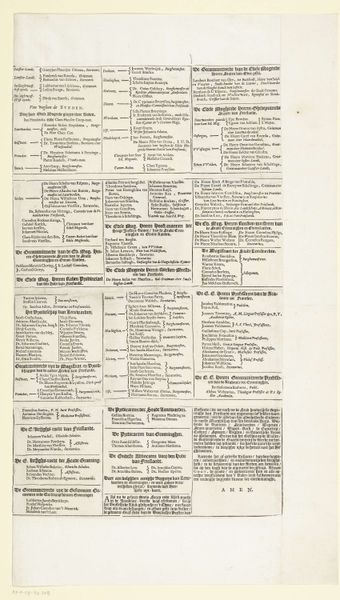

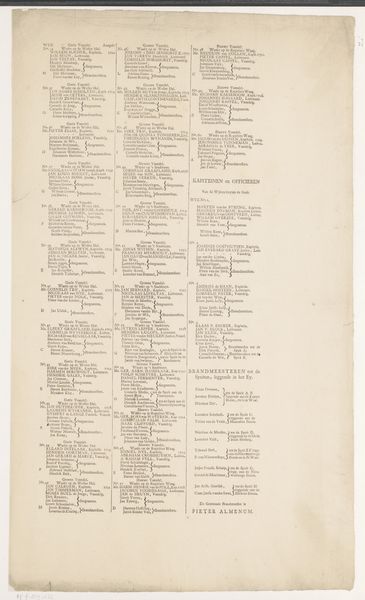

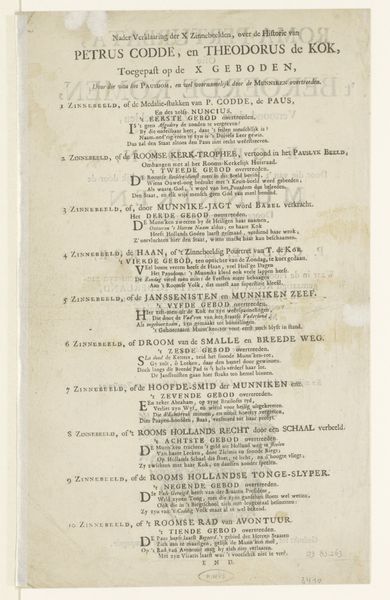

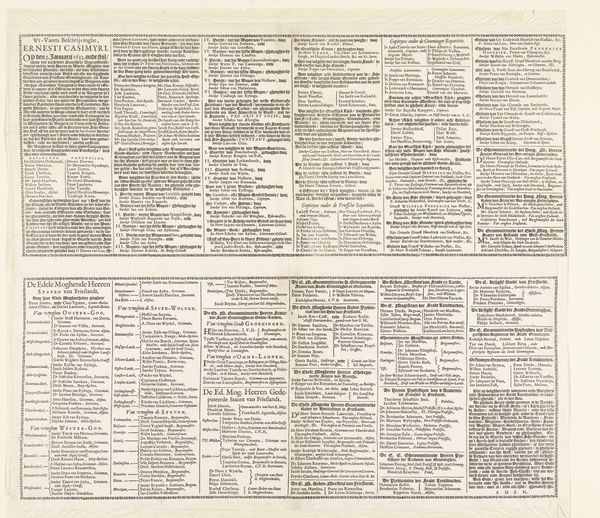

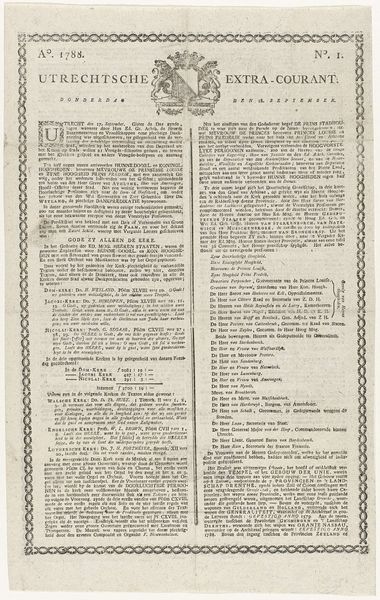

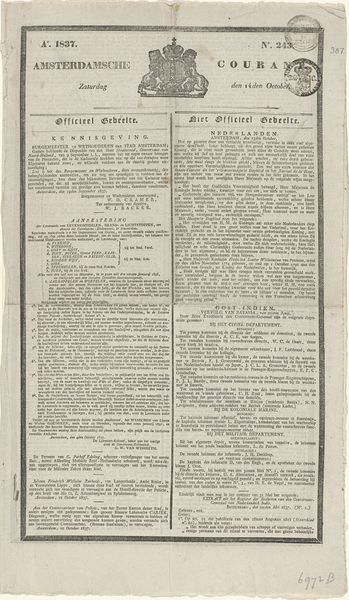

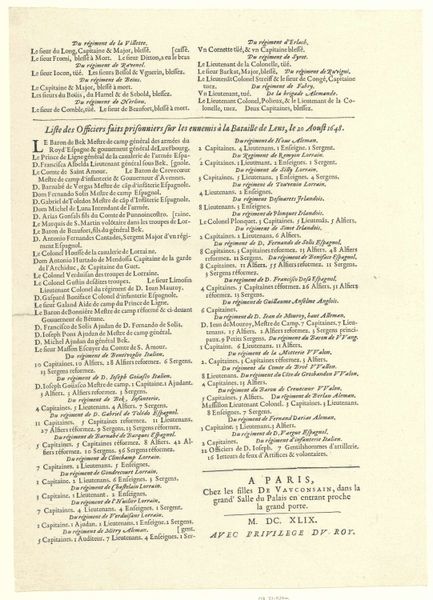

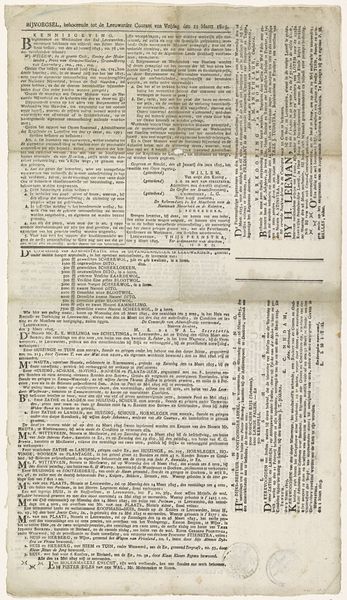

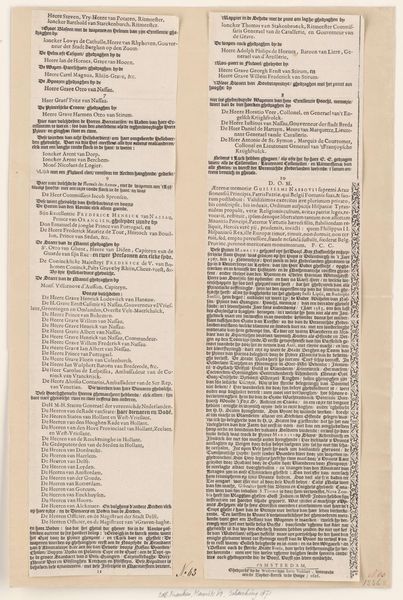

Begrafenisoptocht van Willem Frederik, graaf van Nassau-Dietz (tekstblad), 1665 1666

0:00

0:00

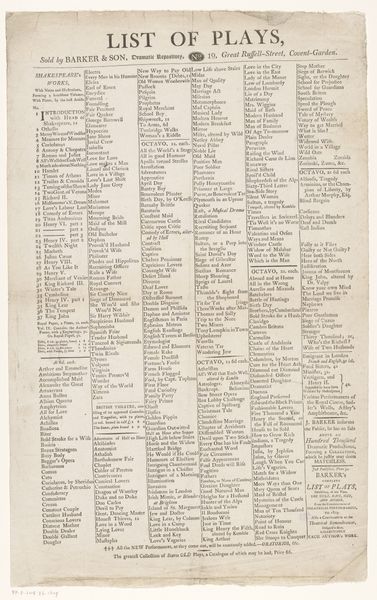

print, paper, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

paper

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 230 mm, width 465 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This detailed print, attributed to Sixtus Regnier Arumtsma and dated 1666, is titled "Begrafenisoptocht van Willem Frederik, graaf van Nassau-Dietz"—or "Funeral Procession of Willem Frederik, Count of Nassau-Dietz." It’s an engraving on paper. Editor: My first impression? It’s like a carefully constructed inventory—somber, highly detailed, but somewhat distant. You know, a meticulous record-keeping more than a poignant memorial. Curator: Precisely. It serves as an elaborate textual document of the social hierarchy present at the funeral. It almost flattens affect into lists—focusing attention on participants' roles and stations. Consider the material implications: the paper, the engraving process itself; they allowed for widespread dissemination and legitimized the social order by visually recording and distributing it. Editor: Exactly. Death as a stage for performing power and solidifying class divisions. Look at the density of text. The names themselves become objects. We read how each region and strata are ordered relative to one another—Dutch society in miniature, mediated through loss. Who is included and, more pointedly, who is conspicuously absent from this "inventory"? It invites inquiry into gender dynamics, or the status of marginalized populations within that era. Curator: Interesting. It brings to mind questions of accessibility, too. Who was meant to read this? Literacy rates, the cost of prints… they shape our understanding of its audience and, by extension, the intended impact of such meticulous documentation. Were these documents like calling cards, silently reaffirming status? Editor: It makes me wonder, too, about the agency, or lack thereof, inherent within its production. Who commissioned it, and what agenda did they serve by detailing this procession in such a way? Where were its consumers located, geographically and within that society's matrix of control? The printing is excellent, but its artistic merit is arguably secondary to the socio-political narrative it silently conveys. Curator: I agree entirely. Considering the labor involved—the engraver's skill, the distribution networks—it becomes a fascinating artifact reflecting 17th-century Dutch society's values and power structures, material means becoming a portrait itself. Editor: Absolutely. Shifting focus toward understanding whose voices go unrecorded offers important possibilities for analysis. This opens further debate surrounding its lasting cultural impact and place among collective imaginings then versus those recognized now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.