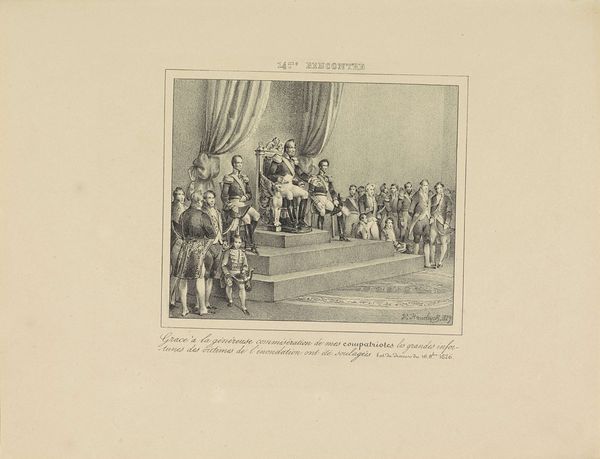

photography

#

portrait

#

asian-art

#

photography

#

orientalism

Dimensions: height 136 mm, width 197 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's discuss this striking albumen print entitled "Portret van de maharadja van Bharatpur tijdens een durbar", capturing a durbar—a formal assembly—sometime before 1874. It's attributed to the studio of Shepherd & Robertson. What's your initial response to the imagery? Editor: It projects such formal power. But look closer, and I sense tension. It feels less like celebration, more like a staged declaration—power carefully curated, each figure deliberately positioned, yet perhaps a bit uneasy under the colonial gaze implied in the photograph itself. Curator: Absolutely. The durbar was a ritual saturated with symbolic weight, from the attire and posture of the Maharaja, alluding to lineage and divine kingship, to the layout indicating social hierarchy, a visual order of the cosmos reflected on earth. We need to consider that such events are acts of self-representation within systems of British Colonial influence. The very act of photographing such an assembly turns the whole setting into a staged construction. Editor: And notice how the light, in that pre-electric era, throws long shadows. While realism is clear here, I question whose “reality” this captures, whose story it actually tells. The camera's gaze intersects with political forces—what gets seen, what gets hidden, whose voice carries across the archive. I see those layers of power dynamics at play in what would otherwise seem just to document this durbar, this photograph freezes, codifies, and thus transforms lived events and ongoing historical realities into fixed imagery and perhaps oversimplified historical truths. Curator: You’ve pointed out some insightful nuances. It calls forth questions about image manipulation and preservation of colonial legacies within photographical practice, as it seems the event was being staged as evidence, rather than only the capturing of a likeness. Considering our present-day re-evaluations, how might people interact with imagery carrying embedded symbols from this period of British colonial influence? Editor: I think we’re past passive reception. Audiences engage critically now, demanding acknowledgement of historical oppressions, seeing representations not as neutral mirrors but as sites of ongoing ideological struggle. The photographic truth itself is never an isolated and single narrative, but we learn and build by examining various critical angles on images such as these. Curator: Indeed, it offers pathways for reinterpreting cultural memory. It’s intriguing how this static, sepia-toned image can stimulate conversations about present-day debates of power, identity, and colonial narratives, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Precisely. By engaging critically, we disrupt simplified readings. We resist the singular "truth," embracing diverse narratives and honoring the complexity embedded within history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.