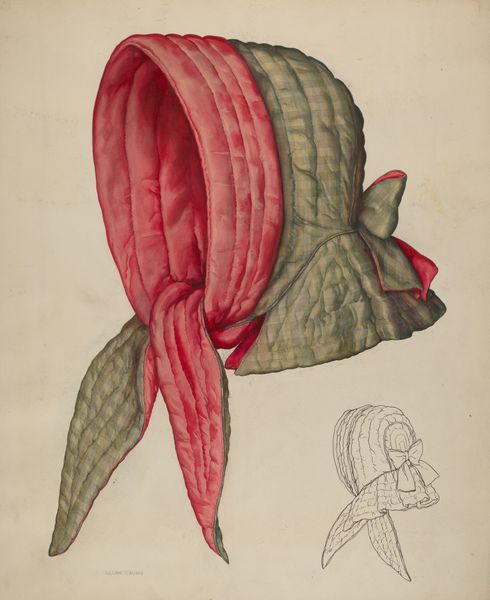

painting, watercolor

#

painting

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

academic-art

#

decorative-art

#

watercolor

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

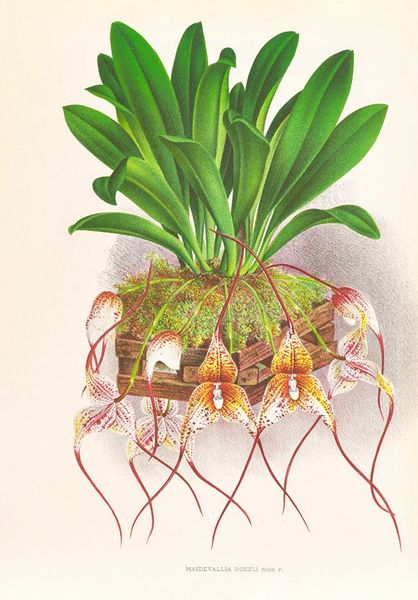

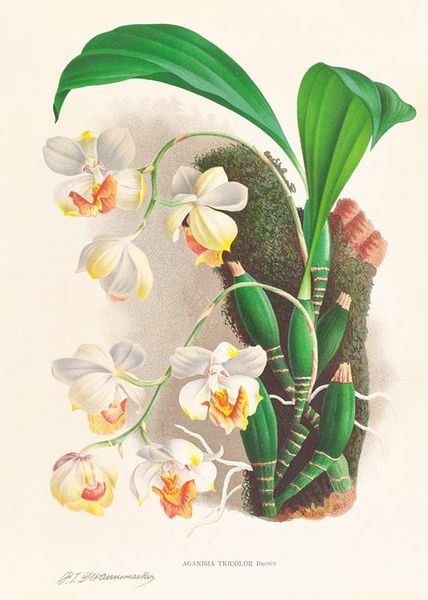

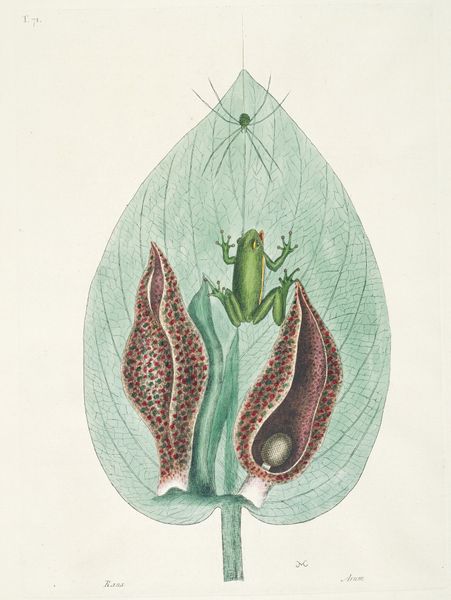

Editor: So, this vibrant watercolour illustration, Coryanthes bungerothi, is by Jean Jules Linden, and it seems to date from around 1885 to 1906. It's quite striking with the bold colors of the orchid contrasted against the almost technical detail of the botanical rendering. What do you see in this piece in terms of its broader artistic or cultural context? Curator: What jumps out is the convergence of scientific documentation and aesthetic presentation. During this period, botanical illustration wasn’t just about accuracy; it was also about showcasing the exotic flora being "discovered" and, to some extent, claimed by European powers. Consider the rise of natural history museums and botanical gardens—how does this image play into that broader trend of colonial science and display? Editor: So it’s less a pure celebration of nature and more…an assertion of dominance, almost? I hadn't considered the colonial aspect so directly. Curator: Precisely! Think about who commissioned these kinds of illustrations, who had access to them, and what purpose they served beyond pure scientific study. It fed a public fascination, a desire to possess a visual representation of the exotic and rare. How does the composition itself – the isolation of the plant, its almost hyper-realistic rendering – contribute to this feeling? Editor: I guess the close-up perspective makes it feel… dissected, analyzed, even appropriated. Also, the very controlled use of watercolor enhances this clinical approach. Do you think the detailed style contributes to the perception of scientific authenticity? Curator: Absolutely. The realism and precise detail lent an air of authority and objectivity, masking the inherent biases present in the act of representation itself. The "academic art" style served to validate the “scientific” observation of the era. It made the exotic accessible – and in a way, possessable – to a European audience. Editor: This definitely shifts my understanding of the piece. It’s more than just a pretty flower painting; it’s entangled with politics of knowledge and representation during the colonial era. Curator: Exactly. The power of images is rarely neutral. Reflecting on these nuances allows us to question how historical dynamics affect even seemingly benign representations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.