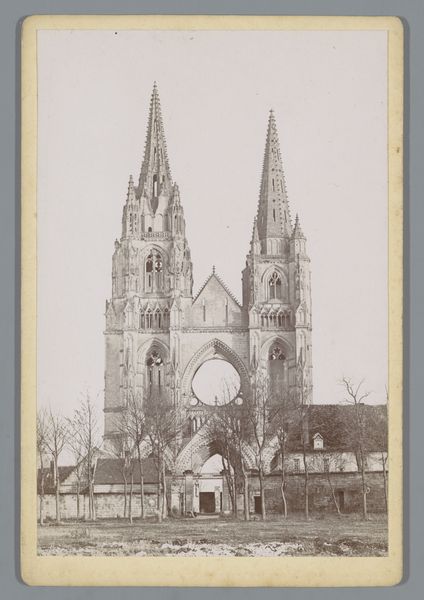

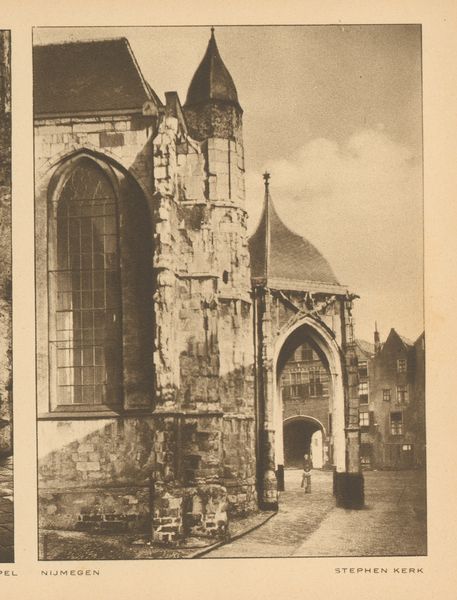

Ruïne van de kerk Saint-Thomas de Cantorbéry te Crépy-en-Valois c. 1875 - 1900

0:00

0:00

medericmieusement

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 354 mm, width 248 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

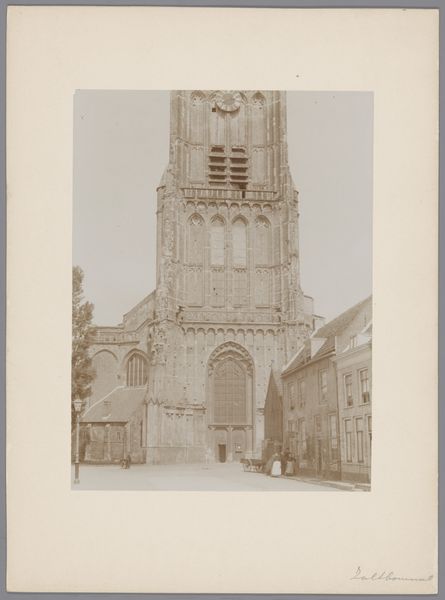

Curator: Standing before us is Mèdèric Mieusement's photograph, "Ruïne van de kerk Saint-Thomas de Cantorbéry te Crépy-en-Valois," dating roughly from 1875 to 1900. The Rijksmuseum holds this gelatin-silver print. Editor: The skeletal remains of that church…it’s powerfully desolate. There's such stark contrast between the imposing structure and the visible decay; one really feels the weight of time and the elements. Curator: Absolutely. Mieusement’s choice to capture it during that specific period—the late 19th century—positions the ruin within debates concerning cultural heritage, national identity, and the impact of industrialisation on rural France. This imagery fed into existing dialogues surrounding societal change. Editor: Yes, but consider the materiality itself: the gelatin-silver process allowing for sharp details that highlight the stone’s texture and the repetitive geometrical forms. And note how the printing creates tonal gradations, imbuing the image with an aged effect, as if time itself has been embedded within the very material. It makes you think of the labor involved in both building and capturing the church's image. Curator: That's a crucial point. Think, too, about the symbolism inherent in photographing a ruin, specifically a church ruin. What does the decline of religious architecture signify about power structures? How did such imagery reflect social anxieties surrounding religion, modernity, and French history at the time? The location also becomes critical: Crepy's location highlights local perspectives of a country undergoing rapid industrial change and rural exodus. Editor: And speaking to the social changes and industrial production you mentioned: consider how advances in photography made this sort of documentation possible. Before industrial advancements, fewer people could encounter images such as this one, meaning that it broadens discussions around whose memories and which pasts were recorded. It opens avenues to new narratives but might exclude others. Curator: Indeed. By focusing on the photograph itself as a crafted object and also interrogating its larger socio-political symbolism, we gain greater insight into the late 19th-century cultural landscape and historical processes that still resonate today. Editor: Right, and hopefully inspiring a deeper examination of not just what we see, but *how* and *why* we see it this way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.