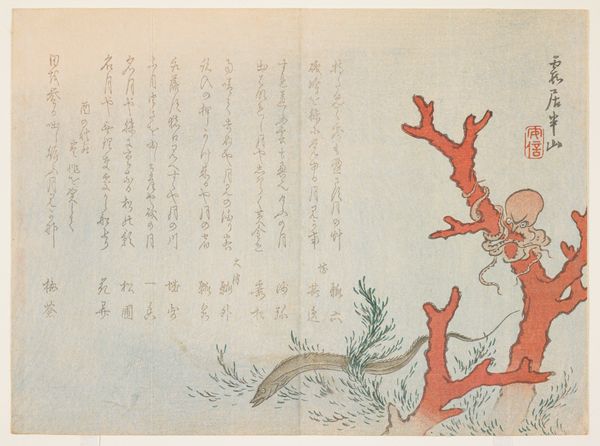

print, paper, ink, woodblock-print, woodcut

# print

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

paper

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

#

woodcut

#

orientalism

#

line

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 15 1/16 x 19 in. (38.3 x 48.3 cm) (image, sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

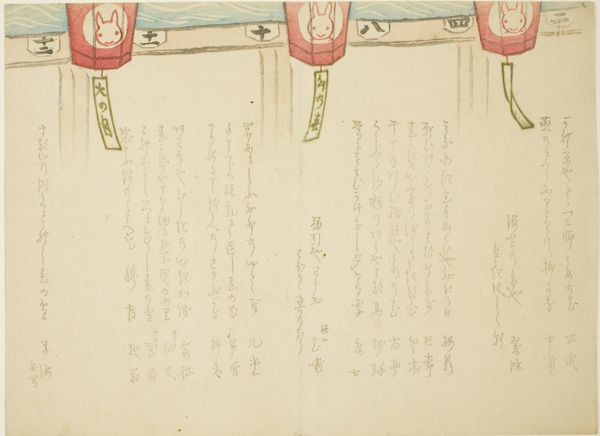

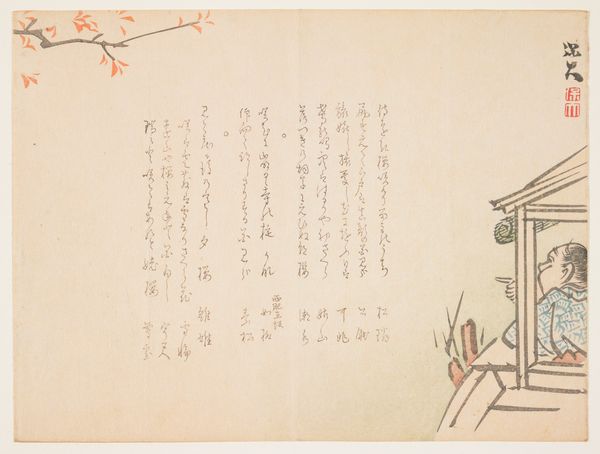

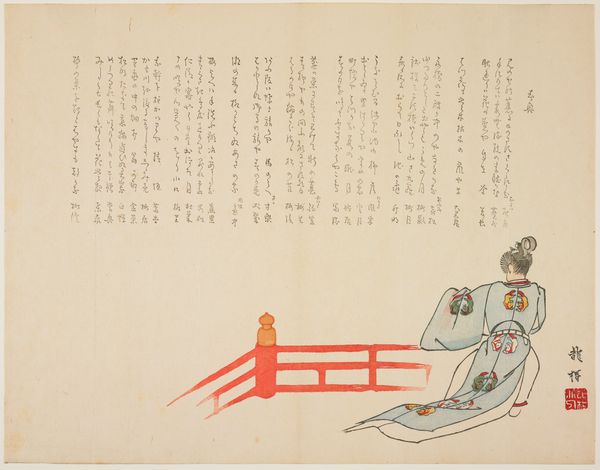

Curator: Here we have "(Bamboo blind)" by Giryō, a woodblock print created sometime between 1818 and 1829. Editor: It’s delicate. And intimate, somehow. The simple lines create a kind of hazy calm, almost like looking at rain. Curator: It’s fascinating to consider the materials here – the paper, the ink, the woodblocks themselves. Ukiyo-e prints were very much a product of their time, reflecting the burgeoning urban culture and economy of Edo-period Japan. They speak to a sophisticated printmaking and distribution system that blurred the lines between art and commodity. Editor: Absolutely. These prints weren't just aesthetic objects; they circulated ideas about leisure, beauty standards, even political satire. Consider the role of women, often portrayed in these prints—were they reflections of reality or idealized projections? The gaze of the artist, the expectations of the consumer – all woven into the image. This particular image begs the question what kind of view it provides, what power that allows to the viewer, and at whose expense. Curator: Precisely! The creation process was quite collaborative. The artist would design the image, and then skilled artisans, essentially laborers, carved the blocks and printed the final piece. Each stage involved its own expertise and potentially its own interpretation of the artist's vision. Editor: And we shouldn’t forget the socio-political climate either. The late Edo period was a time of economic change, social stratification, and the rise of a merchant class with newfound wealth. How did this impact the kind of imagery that became popular? It really highlights the intersection of artistic production, social class, and power dynamics. Curator: Looking at the formal qualities, the seemingly simple bamboo blind is rendered with such attention to the individual reeds. It highlights that the creation of objects, however mundane, is imbued with care and precision from makers working within certain expectations about their time and their output. Editor: Thinking about accessibility, how were these prints viewed? By whom? We should remember these images also played a part in shaping and re-shaping how Japan presented itself to, and was perceived by, the world. Curator: It's a reminder to consider the complex web of labor, material culture, and socio-political context that brought it into existence. Editor: Yes, it really speaks to the intersection of artistic expression and the broader narratives of gender, race, class, and culture shaping our world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.